1963 Aston Martin DP215 Grand Touring Competition Prototype

{{lr.item.text}}

$21,455,000 USD | Sold

{{bidding.lot.reserveStatusFormatted}}

- The most significant one-off Works Aston Martin

- A unique Works Design Project; developed to compete at Le Mans

- Driven by Lucien Bianchi and Phil Hill at Le Mans, 1963

- Clocked at 198.6 mph on the Mulsanne Straight

- Restored with the consultation of Ted Cutting, the original designer

- Fitted with its original engine and correct-type five-speed gearbox

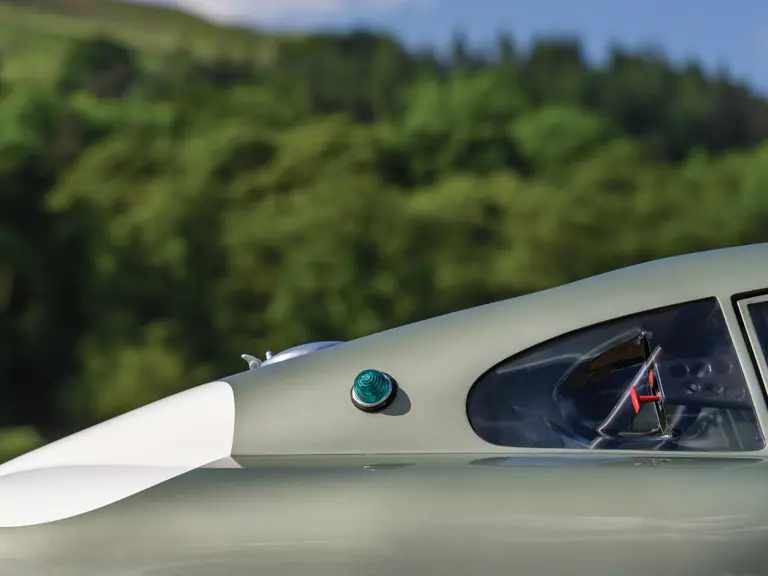

- 1963 Works-built Hiduminium body

- An exceptional and important part of Aston Martin racing heritage

- The final David Brown competition Aston Martin

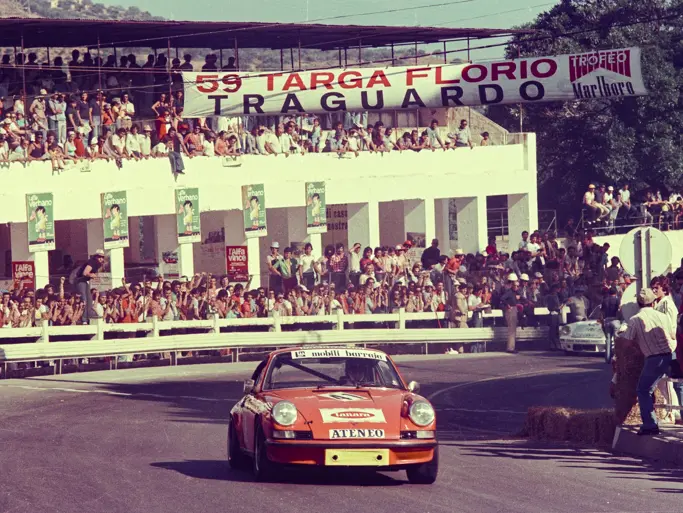

THE ASTON MARTIN PROJECT CARS

After winning the World Sportscar Championship in 1959 following 1st-place finishes at Le Mans, RAC Tourist Trophy, and Nürburgring, David Brown pulled Aston Martin out of sports car racing. After another unfortunate season of Formula 1, which sounded the death knell for machines such as the DBR4, the racing department shut its doors at the end of 1960. For David Brown this was not entirely bad news, as he could focus on his new line of road cars – the previous year had seen the introduction of the DB4GT – and leave the racing to the privateers.

It was not long, however, before the Aston Martin dealers on the continent were begging for a return to Works racing. Their thinking being, rightly so, that factory competition helps sell cars – and so David Brown approved what would become the first of what would eventually come to be four “Project cars” – sports car racing vehicles all developed from the DB4GT chassis.

The first Design Project, DP212, was conceived and executed in five months and was nearly all DB4GT in regard to its chassis and mechanics. The wheelbase was extended by an inch, and instead of the standard platform, replaced by box-frame sections. Truly different was the body shape – very sleek and seemingly aerodynamic, comprised of very lightweight magnesium/aluminum alloy. With an increased engine capacity and triple Weber carburetors, DP212 had a top speed of 175 mph. Driven by Richie Ginther and Graham Hill at Le Mans in 1962, the car placed 5th on the grid.

It became clear, however, that DP212 suffered from rear-end lift at high speed. Both Ginther and Hill complained of it at Le Mans and following tests at MIRA, Aston Martin engineers would find that nearly a quarter of the weight was lost! Subsequently, a rear spoiler was added along with an extended and lower nose; this would help engineers plan for the following Project Cars.

For the 1963 season, two additional Project cars (dubbed DP214) were created to rival Ferrari’s entries. Built for the GT class, each DP214 was required to have a DB4GT chassis number to conform to regulations. In reality, however, the chassis was entirely different from standard. To lighten the vehicles even more, the box-section chassis was drilled, and the frame had aluminum floorpans attached. Bending the rules even further, the engineers moved the engine back by eight inches, ensuring less rear-end lift. The engine capacity was increased yet again, and both cars were fitted with a David Brown S432 four-speed gearbox. The body was also designed with DP212 MIRA tests in mind: both DP214s were fitted with a low nose cone ending in a smaller radiator intake, and a sizable Kamm tail, giving the bodies a truly magnificent aspect. All in all, DP214s were a full 13 kg lighter than DP212, and nearly 200 lighter than a DB4GT. Both DP214s would go on to compete in the 1963 and 1964 race season, winning both the Coppa Inter-Europa and the Coupes de Paris, while also scoring other podium finishes. Notably, at Monza, the DP214 driven by Roy Salvadori defeated the Works 250 GTO driven by Mike Parkes in the three-hour race supporting the Italian GP.

DESIGN PROJECT 215

It was the Works entry for the 1963 Le Mans Prototype Class that truly set the bar for what the Aston Martin engineers could do. A wholly unique competition car, the Aston Martin Design Project known as DP215 was to become the last racing car built by the factory, and the ultimate evolution of the Aston Martin GT racers. It was ordered by John Wyer, designed by Ted Cutting, had an engine from Tadek Marek, and was driven by Phil Hill – the great names associated with DP215.

TWO MONTHS TO LE MANS

It would be laughable today – a team manager sending a memo to the engineering department in March stating the exact specifications for a car that was to be ready for Le Mans, just two months away. And yet, for John Wyer, that was par for the course, as was the notoriously precise man setting a budget review at just £1,500. For Chief Engineer Ted Cutting, however, the project that would become DP215 allowed him to showcase his incredible automotive genius.

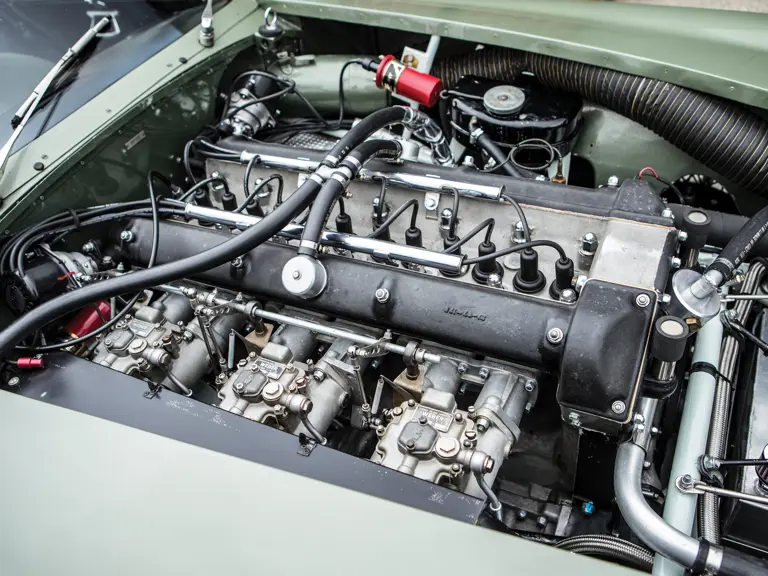

Though very similar in looks to the two prior DP214s, DP215 is a very different car under the skin. Originally created as a vehicle for Tadek Marek’s yet-to-be developed V8, for the 1963 season, DP215 was equipped with a four-liter version of the DP212 six-cylinder twin plug engine – although 400/215/1 was fitted with a dry sump oil system. Modifications to the steel box-frame chassis included allowing for the engine to be fitted a full 10 inches further back than in DP212, as well as independent rear suspension. Ted Cutting was focused on improving balance and aerodynamics – the culmination of years of wind-tunnel testing at MIRA in response to driver complaints of rear lift at high speed.

Just two short months after John Wyer’s memo, Phil Hill and Lucien Bianchi drove DP215 in the 1963 24 Hours of Le Mans. It recorded at 198.6 mph along the Mulsanne Straight . . . and had not even reached top speed yet! Indeed in practice, the car became the first car to officially break the 300 kph barrier. Its lap time put it in amongst the Ferrari rear-engined prototypes. It was six seconds a lap faster than the Ferrari 330 LMB running in the same class and 12 seconds a lap faster than the Ferrari 250 GTOs in the GT class. DP215 looked to be a sure winner. Unfortunately, the DBR1-type CG537 gearbox failed due to the high torque of the four-liter engine, and DP215 retired after two hours.

Repaired and entered the next month at Reims and driven by Jo Schlesser, DP215 again looked to have a win in its sights. However, the since repaired transmission caused Schlesser to miss a gear and over-rev the engine – forcing DP215 to retire while leading the race. With two DNFs behind them, the engineers were able to fit the gearbox originally intended for the car: the S532. Though entered at the 1963 Brands Hatch Guards Trophy, tax regulations kept David Brown from racing the car. With John Wyer turning in his resignation, the racing department lost its lynchpin. In November 1963, the British press reported the Aston Martin Racing Department officially closed.

After shutting down its racing department, Aston Martin sold the team cars but kept DP215 for development in the hopes of an eventual return to racing in 1965. These hopes were shattered, however, when DP215 was in an accident during night testing on the M1 motorway.

RESTORING DP215

Sold to Malcolm Calvert from Aston Martin in 1974, DP215 had by this time lost some of its original parts. Its four-liter engine was sold to privateer Colin Crabbe for his DP214, and the extremely rare S532 gearbox was lost to time. Calvert, from the Isle of Wight, began what would become a long-term restoration project, spanning several owners. The factory fit the original, 1963 Works DP214/215 spare body on what was a slightly bent chassis. Photos of the car being picked up from Aston Martin by Calvert show that the car was a complete bodied rolling chassis, retaining many of its unique original parts, including the suspension, rear differential unit, dashboard, instruments, pedals, etc. Not interested in racing DP215, however, Calvert also fitted a DB6 engine and ZF gearbox. For several years he used the car on the road, before selling it in April 1978.

Purchased then by Nigel Dawes, a noted Aston Martin collector, the restoration work continued. Determined to make all aspects of DP215 as original as possible, Dawes began working with Ted Cutting, the original designer. With Ted on board as a consultant, Dawes searched for several years for the original engine before finding it in DP214 – now converted to wet sump. In lieu of the original and with Ted’s full support, Dawes managed to obtain the Indianapolis Cooper-Aston 4.2-liter engine. Once Forward Engineering reworked the engine to a dry sump, Dawes had an engine as close to the original as was possible. At great expense three original sandcast 50 DCO Weber carburetors were added, the chassis and engine were sent to Chapman Spooner for final modifications, and the body shell was restored, with Ted Cutting addressing the necessary work to be done. The interior was also restored, and Dawes even managed to find the correct, original seats which he had re-covered in a green corduroy which matched the 1963 fabric. A true success, Nigel Dawes' restoration saw DP215 restored to its former glory, excepting the original engine and the S532-type gearbox.

Having left his mark on DP215, in 1996 Nigel Dawes sold it on to the next custodian, historic racer Anthony J. Smith. Now of a condition to be used on the road and track safely, Smith enjoyed DP215 at a variety of events, including the Goodwood Festival of Speed and TT Revival.

In 2002, the current owner traded a Formula 1 Ferrari for Smith’s DP215; at the time he was looking for a car he could drive on the road comfortably, yet still run as a race car when it suited. Entering the final stages of DP215’s restoration saga, the owner and his son contacted Ted Cutting once again and requested his help to rebuild a brand-new correct-type S532 transmission utilizing Ted’s original plans and the box from DP212 as the standard. Only six of these gearboxes were ever made: two for Works Lagondas, two for the DBR2s, one for DP212, and one for DP215. Working with noted specialists Richard Williams and Crosthwaite & Gardner, the arduous task of crafting the over 1,000 parts that make up the gearbox began. Upon completion, small modifications to DP215 were made to reverse the changes that had been necessary when a ZF gearbox had been fitted. Finally, only one puzzle piece remained.

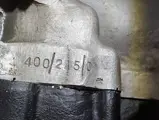

ENGINE NO. 400/215/1

The owner himself will tell you that the Indianapolis Cooper-Aston engine was perfect in DP215, and it is doubtless that he enjoyed hours of time behind the wheel of the Aston Martin. Over 10,000 miles, down to Italy and the South of France, through the center of Paris, and over every road in Scotland, the owners have driven DP215 likely more than any of its previous drivers combined. Yet, all this time its heart was still missing – just tantalizingly out of reach in its sister car.

The owner set out with the intention to restore the original engine to DP215. No small feat, considering the engine spent half a century with DP214 – yet the owner was fiercely determined. Finally, the deal was done, and 400/215/1 was at last reunited with DP215.

Installed by Chris Woodgate, the engine had only run an estimated 300 miles since an RS William rebuild in 1992. When fitting the dry-sump components that had been created for the Cooper-Aston, the engine was inspected, and everything was found to be perfect, nearly brand new. When Chris Woodgate ran an engine dyno to fine-tune the calibrations, the engine recorded a comfortable 300 bhp – and that was not even a maximum power run, showing that the original Le Mans test figure of 326 bhp should be readily available, if desired. Whole again, DP215 is as on the button as any new owner could hope for.

“I was astounded by the six-cylinder engine’s torque, particularly at Tertre Rouge corner, the last one before the Mulsanne Straight. Le Mans cars have such high gears for the straight and often feel dead leaving that right-hander. Not the Aston, which felt quite meaty out of Tertre Rouge and away. And flat out it needed only the lightest steering pressure,” said former world champion and triple Le Mans winner Phil Hill talking about driving DP215 at Le Mans in Inside Track.

The consignor, who has also driven at the Le Mans 24-hour race and has had the good fortune to own three Ferrari 250 GTOs over the years, feels that Phil has absolutely focused on the key aspects of the car. He notes:

“The lines of the car are absolute perfection. You can see where its outstanding maximum speed came from. From a driving point of view, the acceleration in second and third gears always caused the hairs on the back of my hand to stand up. The previous engine fitted to the car was giving 372 bhp on the dyno, which gives some indication as to what extent the original engine, now fitted to the car, could be developed. The steering is delightfully light (unlike other Aston Martin GT cars of the period), the brakes are outstanding for the era, and the car feels like a thoroughbred to drive. Close examination will show that the build quality is superior to virtually any other competition car of the period.”

“My outstanding memory of the car is when I was following the DP215, driven by Paul Vestey, in Paul’s GTO – we were driving on some magnificent roads down to Taranto in Italy, passing and repassing each other at speeds in excess of 130 mph. The sound of the two old warriors was unforgettable. The Aston’s six-cylinder bark perfectly complimenting the Ferrari’s V-12 howl.”

“It must be said that despite the car’s extraordinary performance, it is easy to drive at slow speeds and in modern traffic conditions. I once drove it through the Paris rush hour traffic on a Dunhill Rally to the Ritz Hotel in the center of Paris. The clutch is light and the new synchro, in-line, five-speed gearbox is a joy. The torque of the engine enables the car to be comfortably driven at 2000 rpm in fifth gear. It pulls cleanly from there all the way to 6,200 rpm if needed.”

“I will always remember that when I asked Ted Cutting what his proudest achievement was during his magnificent career with Aston Martin, he replied that winning the World Sports Car Championship in 1959 with the DBR1s came a very close 2nd to the recorded speed at Le Mans of DP215. This was the fastest speed ever recorded by a front engine car on the old course at Le Mans. He was talking as a designer, of course. I hope that whoever is fortunate enough to become DP215’s next custodian drives and enjoys the car as much as I have done over the years.”

Stunningly beautiful, with an engine that is as comfortable at 40 mph as it is at 180 mph-plus, it is not hard to see how unbelievable this car would have been in 1963. Although it might represent the end of an era for Aston Martin, now reunited with its original engine, DP215 is looking toward a fresh start.

| Monterey, California

| Monterey, California