Art has always been about stretching boundaries. It is about starting with the acceptable and pushing it beyond its limitations. It is about taking expectations and blowing them away with audacious fervor. It is about provoking astonishment through unbridled creativity.

By these standards, Harry C. Stutz was an unlikely artist. Perhaps a few in the stands at Indianapolis in 1911 saw Stutz’s creation coming, but they were in the minority, as they were engineers and fellow veterans of the early automobile industry, and they knew Stutz’s genius. The car that he built under his own name averaged 62.375 mph for 500 miles in that first running of the 500, running with only minimal mechanical adjustment and 13 pit stops, with 11 of which being for tires. Though it did not win the race, its durable performance was considered outstanding for a first independent production effort. Stutz took advantage of the notice, promoting his car as “The Car That Made Good In A Day.”

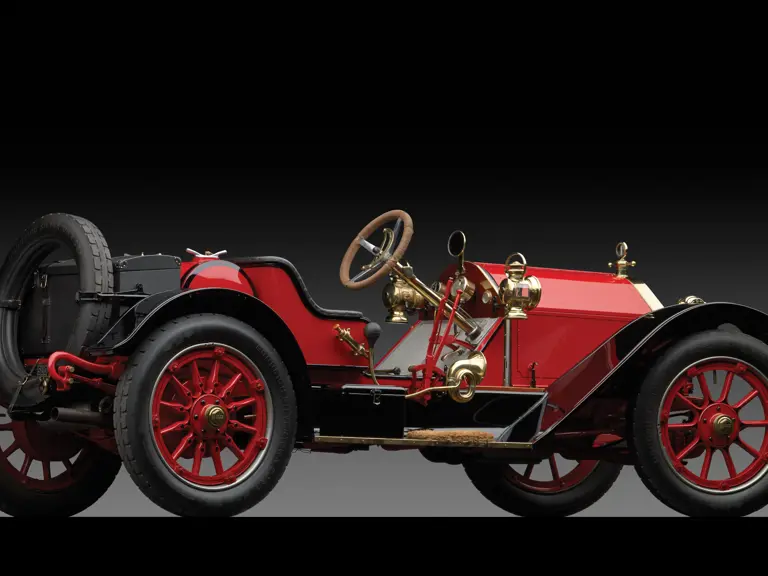

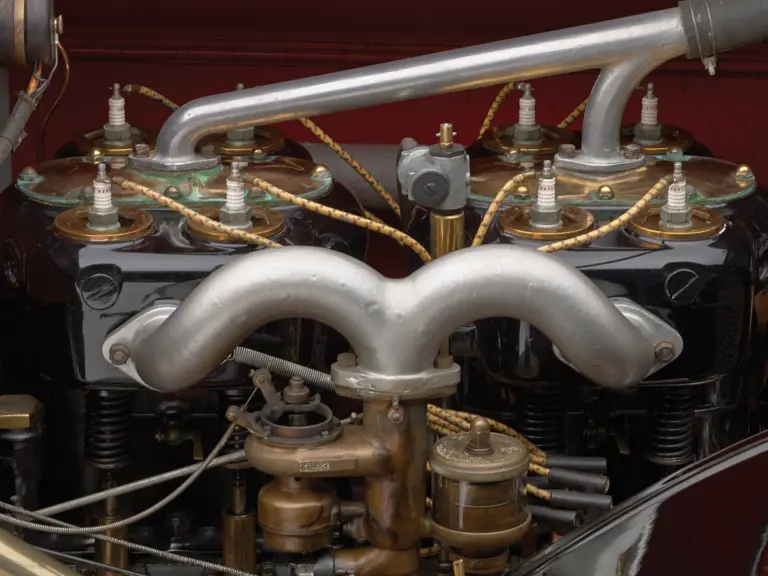

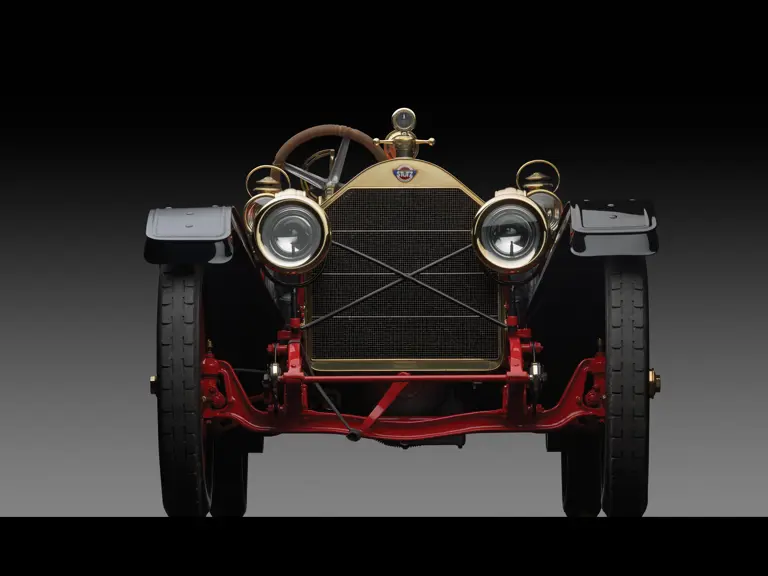

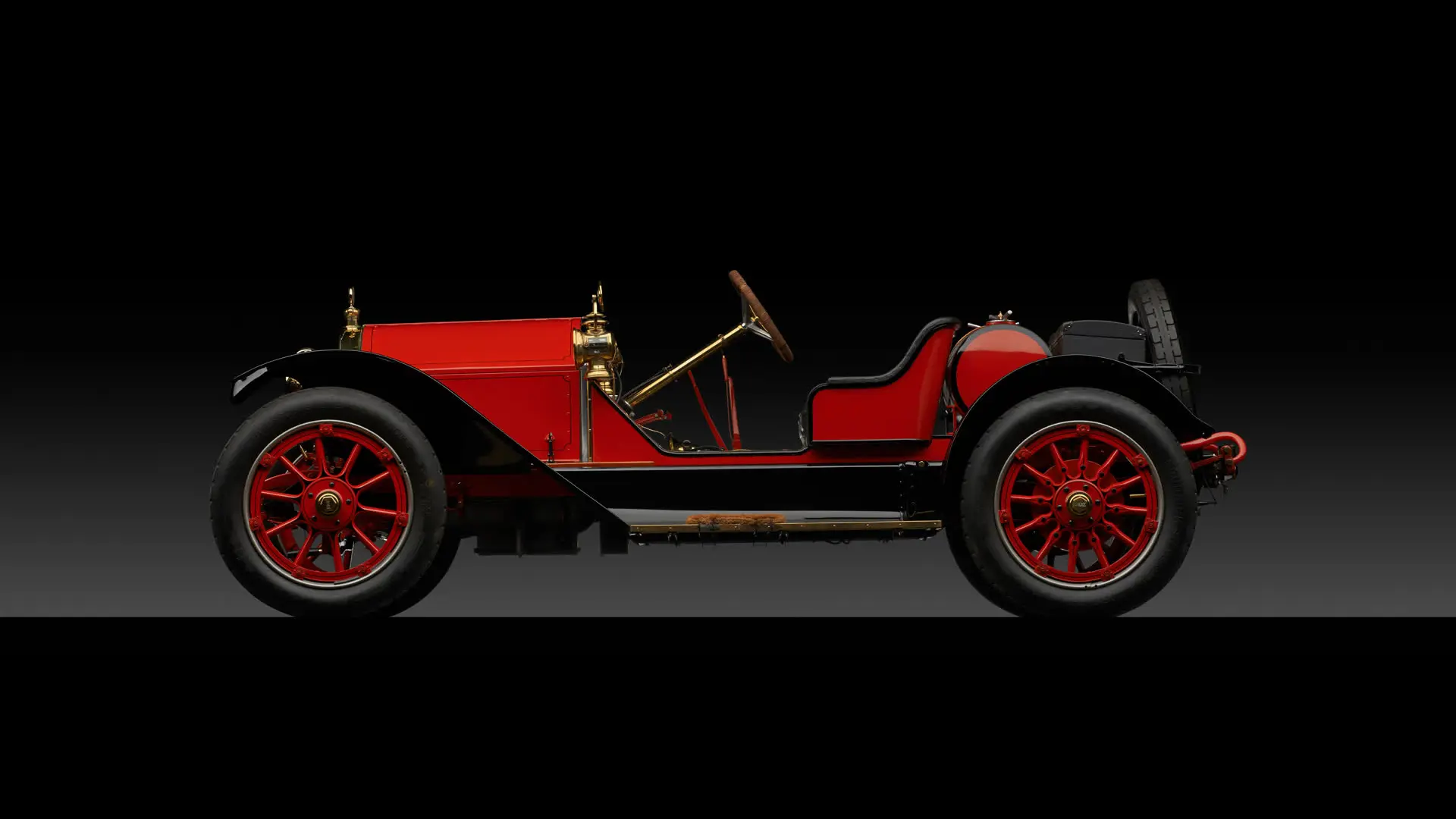

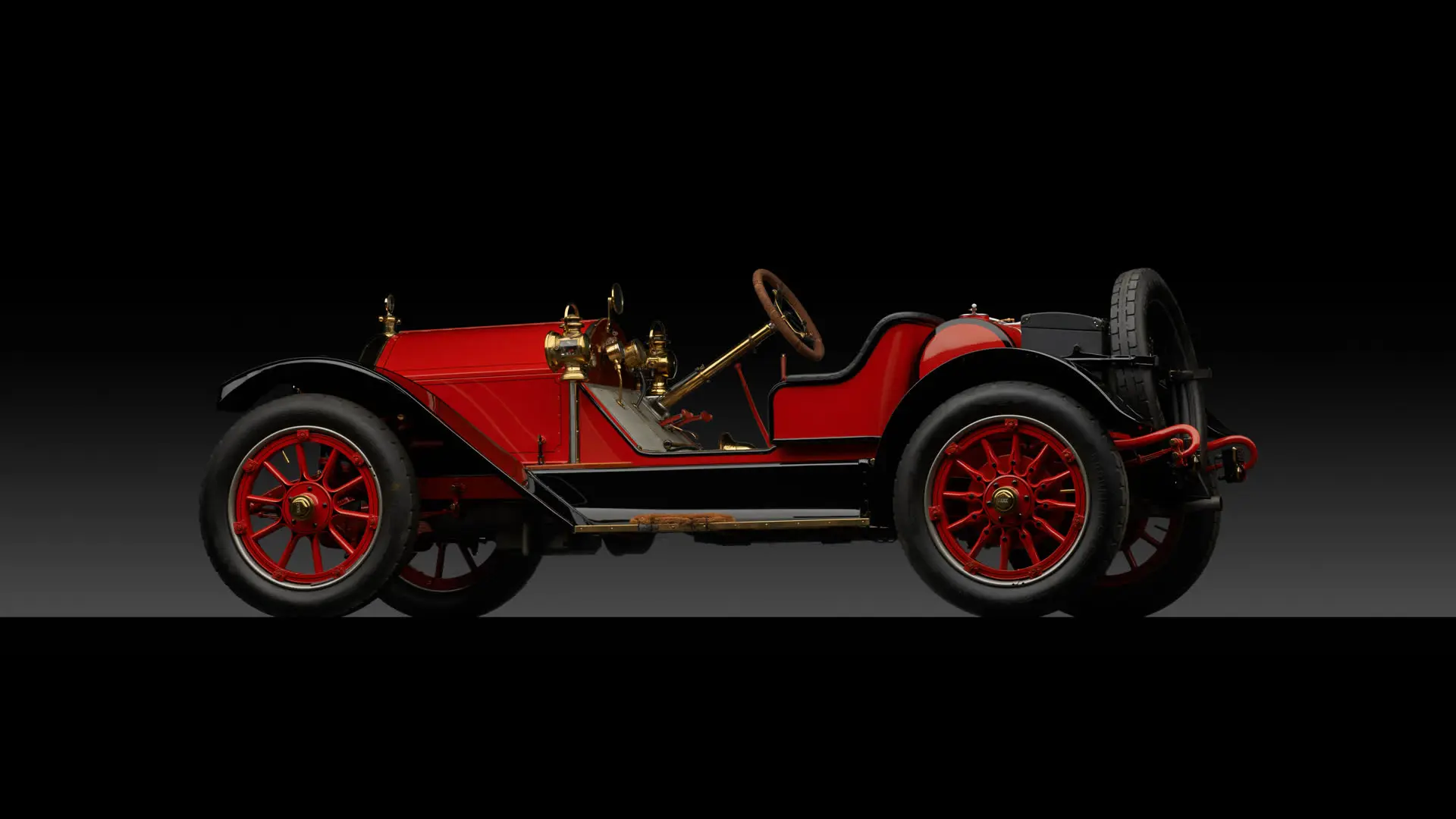

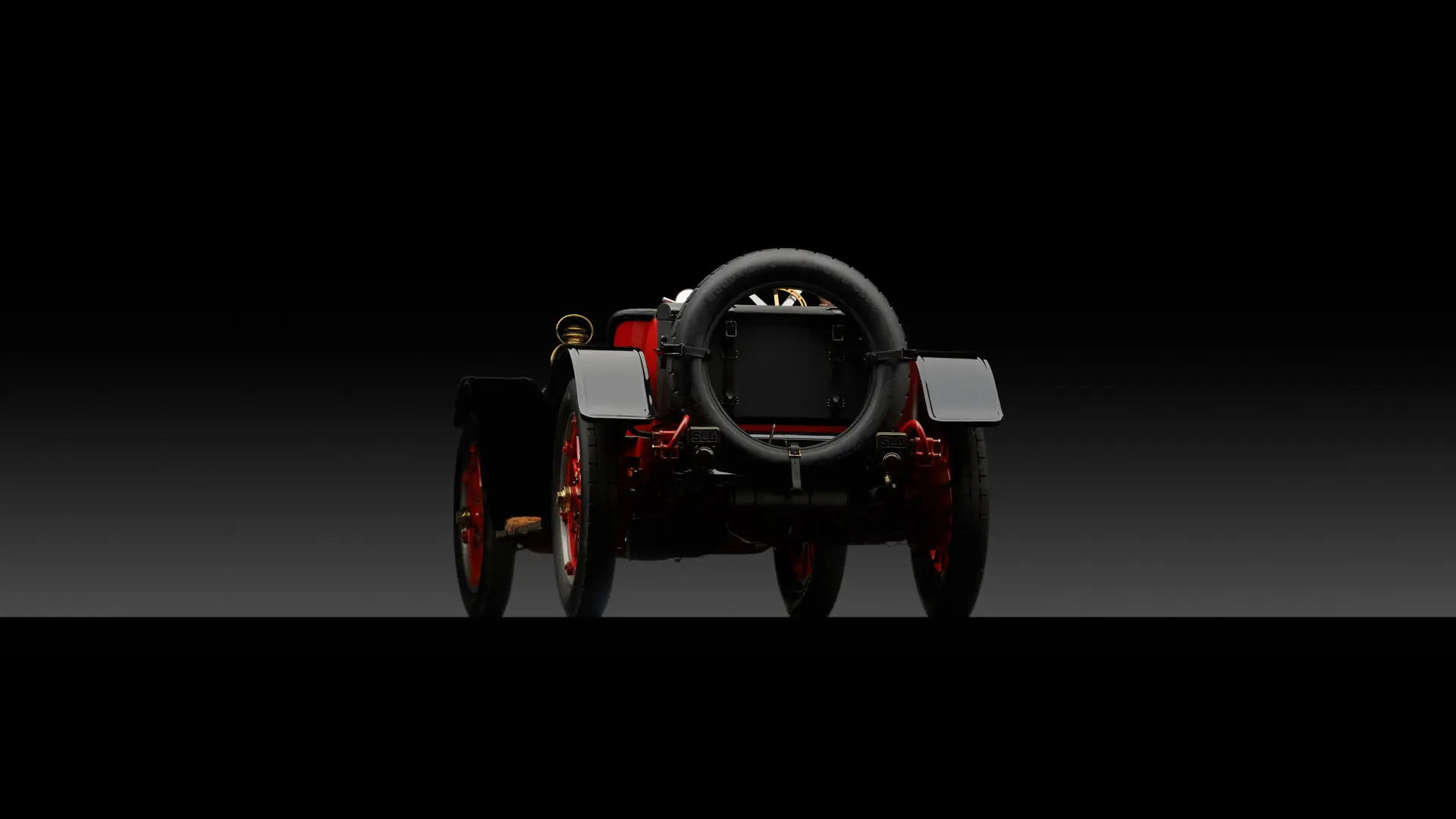

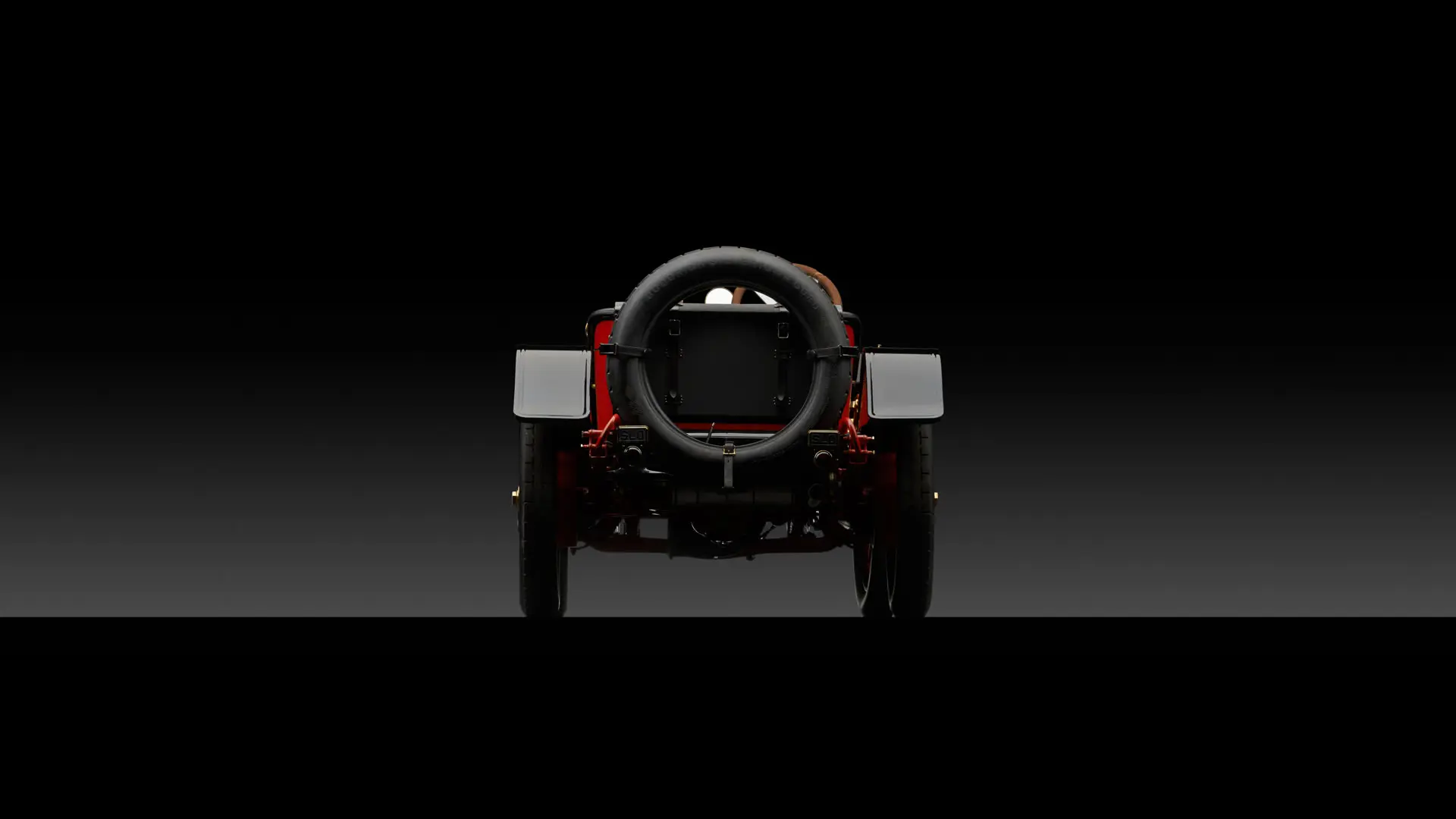

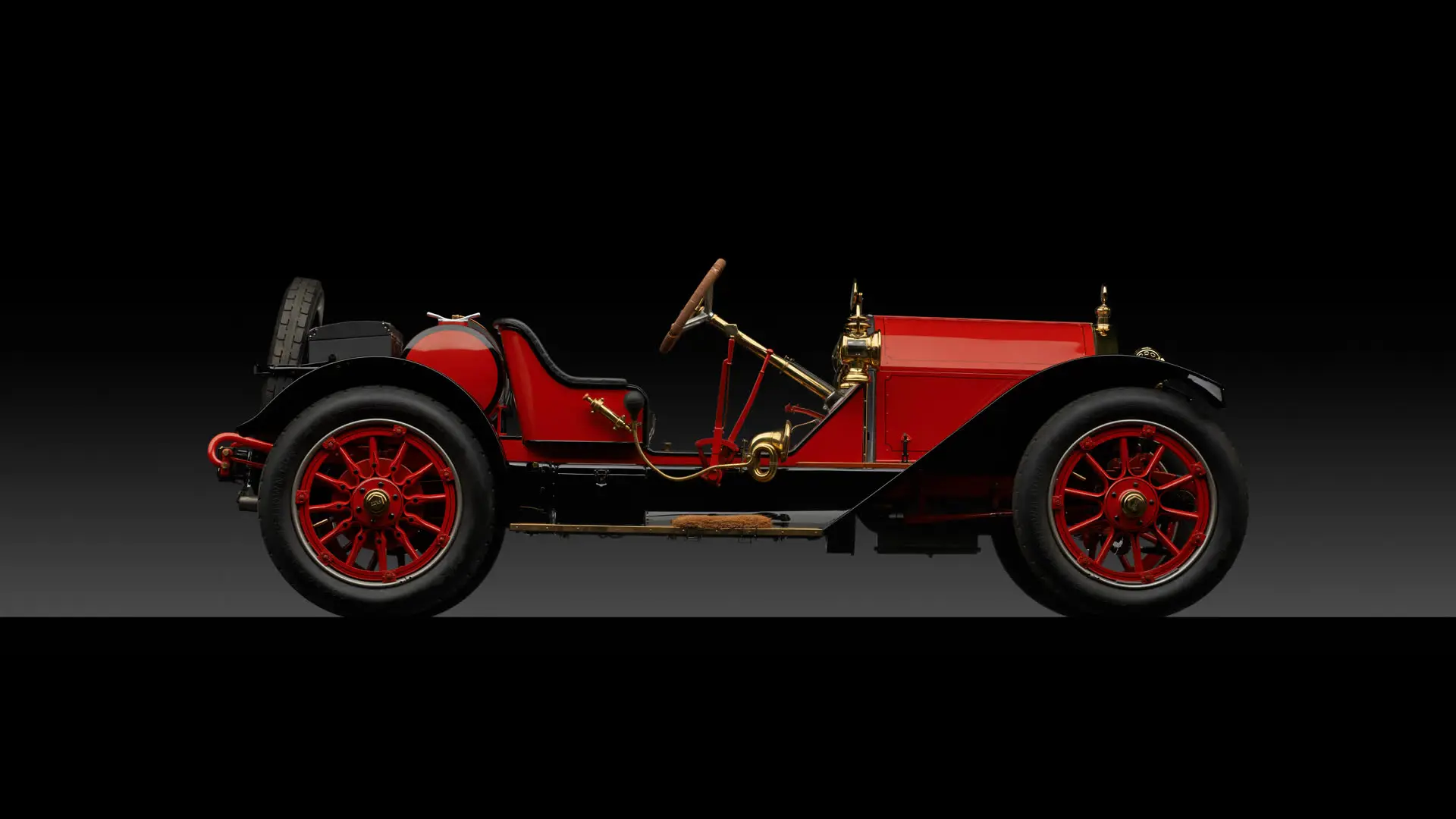

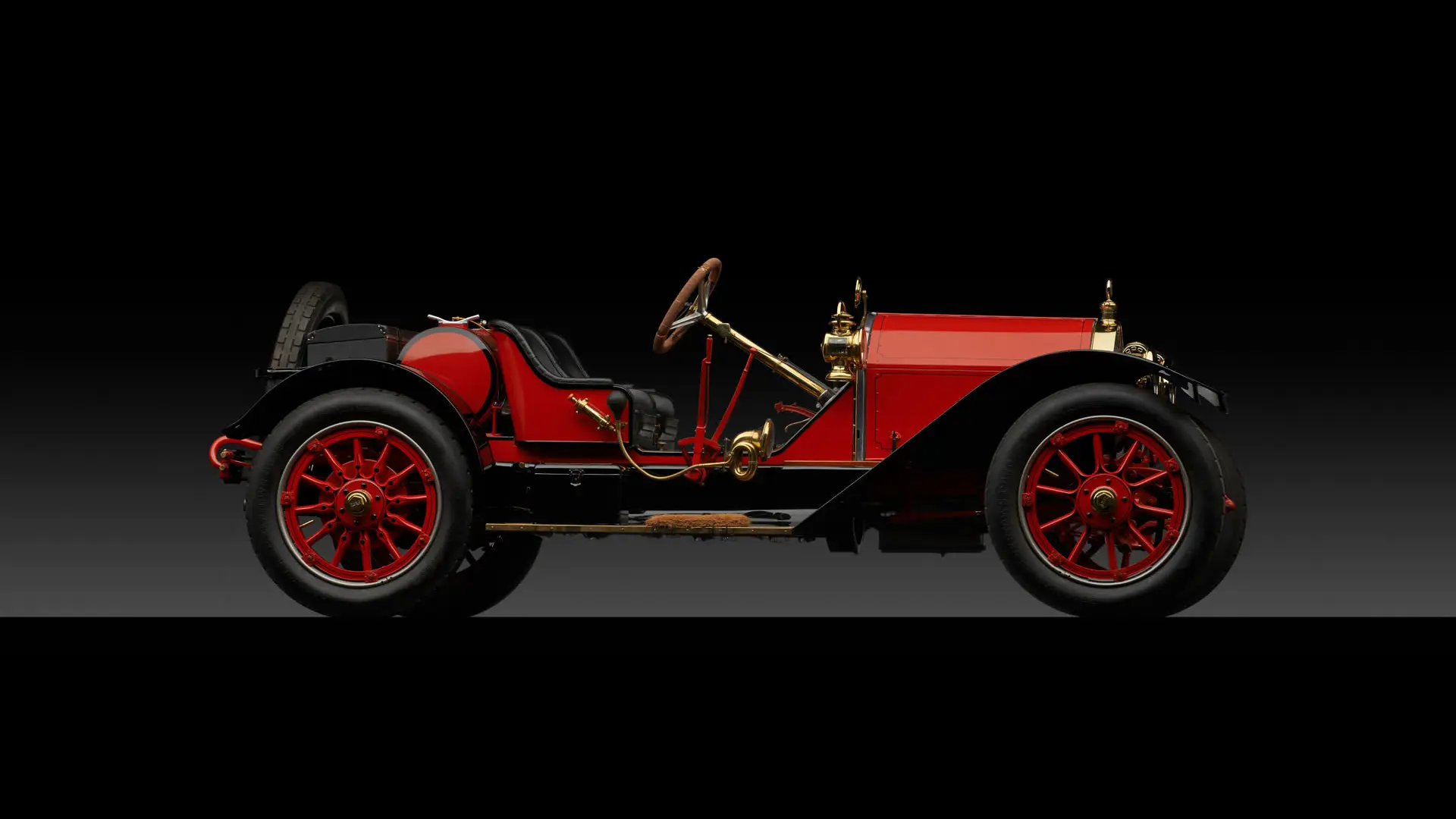

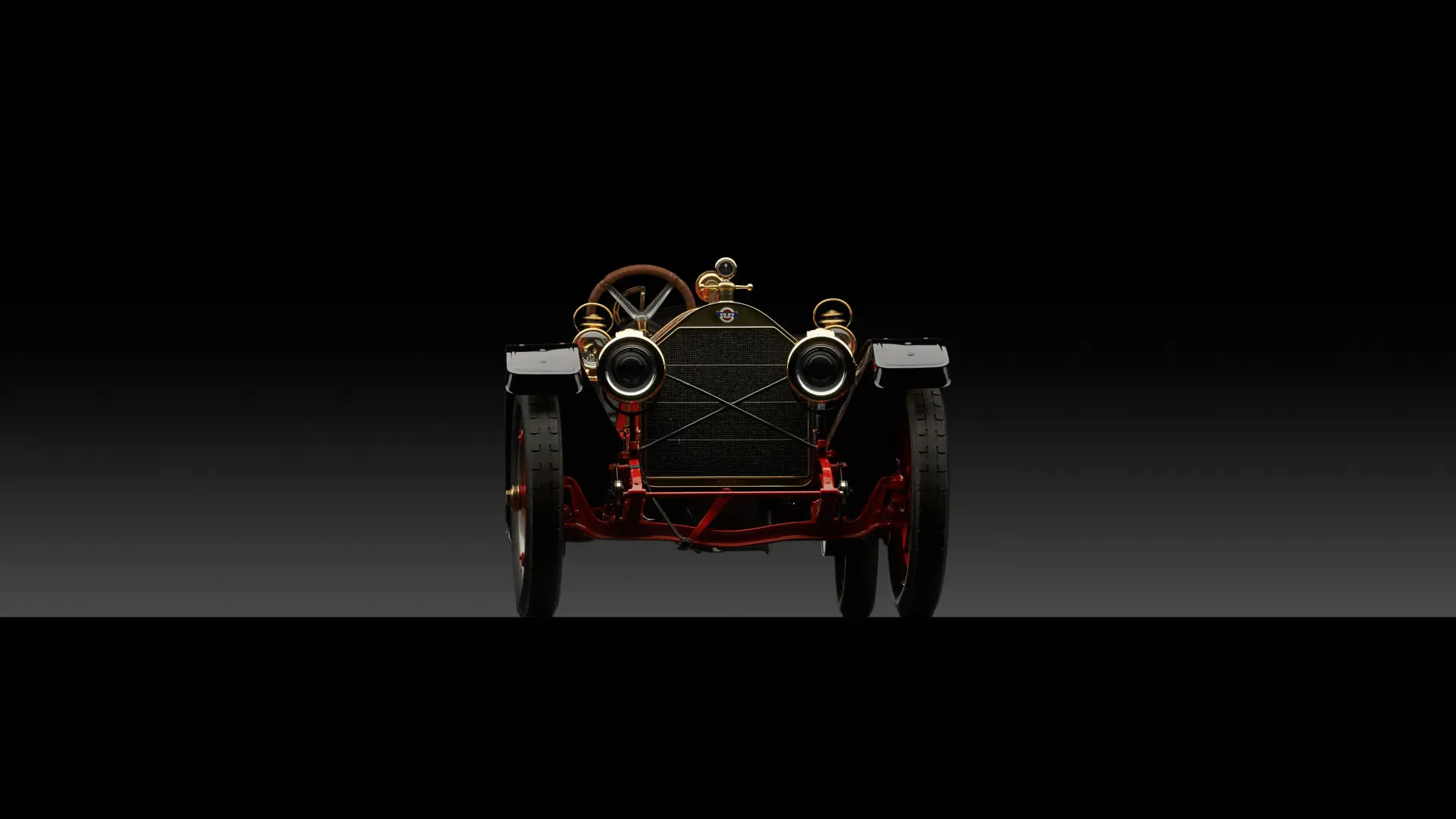

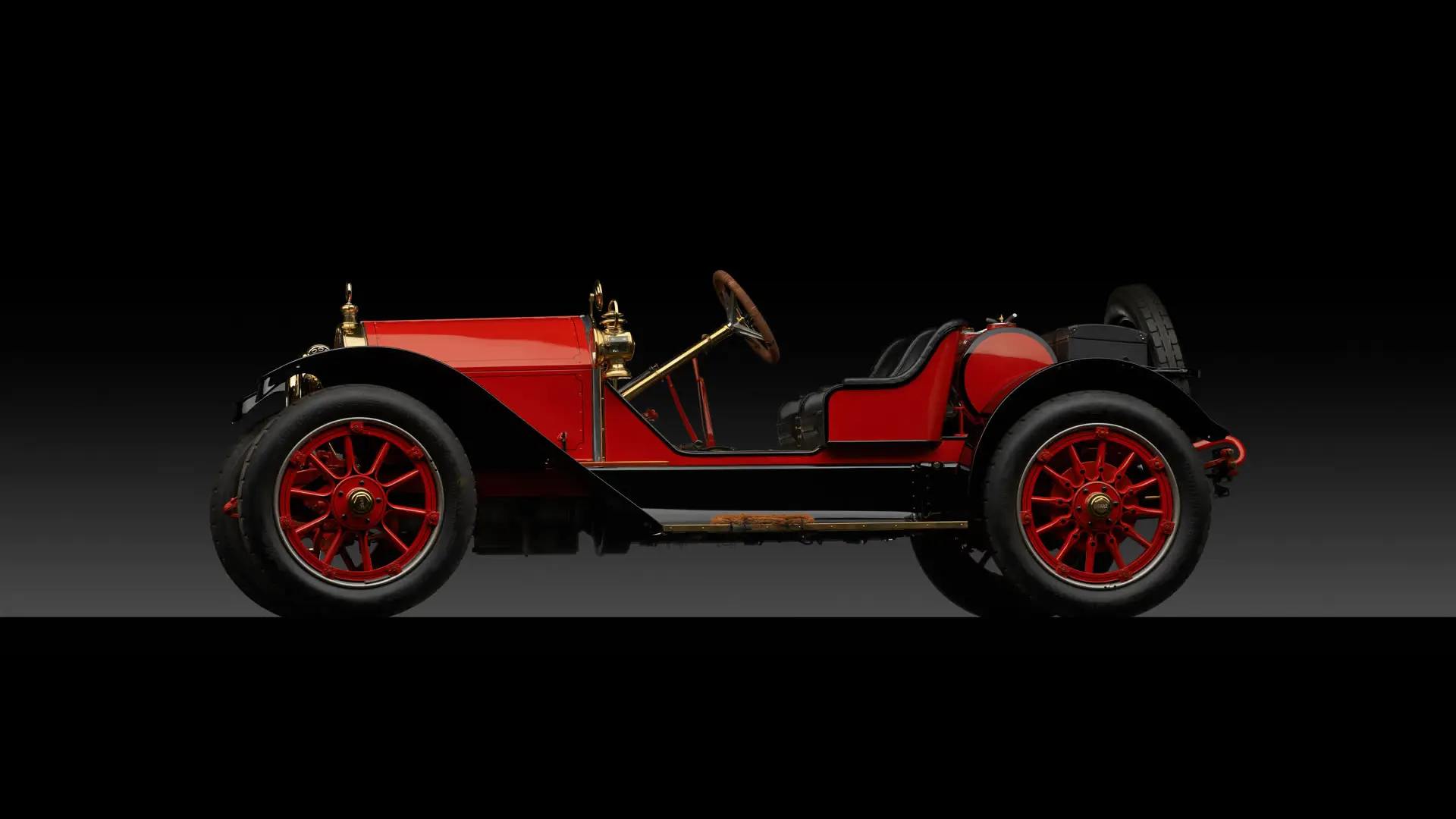

The production version of that car was the machine offered here, the Model A Bear Cat of 1912. (This year only, the Bear Cat was spelled with two words by the factory.) It was powered by a Wisconsin-built mill that Stutz historian Raymond Katzell referred to as “of appropriate size, that had already accumulated a splendid record for stamina and performance in racing.” Harry Stutz’s mechanical brilliance increased the engine’s performance to an estimated 60 horsepower, which was fed to the rear wheels through a transaxle—a technological advancement that was some five decades ahead of its time. When installed on a 120-inch wheelbase chassis with the Bear Cat’s barely-there bodywork, which was just seats and tanks, the Wisconsin T-head four resulted in superb speed from an already extremely lightweight performance-designed chassis.

The sporty Bear Cat was promoted by Stutz to the carbon copy of their racing model. “We are now building duplicates of this ‘car that made good in a day’ with absolutely the same material, workmanship, and design,” boasted the 1912 factory catalogue. True indeed, as men of the era, with money to burn and gasoline in their blood, took to the dirt and board tracks in Bear Cats, setting up a heated rivalry with competitors, most famously the Mercer Raceabout, of New Jersey. Every spectator who knew the dust of a race also knew the taunts: “You gotta be nutz to drive a Stutz!” “But it’s worser to drive a Mercer!”

It was the Bear Cat and its competitors that put American performance on the map. They made American-built cars powerful, brawny, and, yes, even sexy. They did it the same way artists launch themselves, by succeeding against the odds with a mixture of creativity, salesmanship, and talent, and by ingraining into the public’s imagination an image that had never been seen before: the picture of speed, etched in brass and steel.

THE BEAR CAT OF CALIFORNIA

Harry Stutz was by all accounts as brilliant in sales as he was in the engineering department. While most automakers of the Brass Era were regional, Stutz wanted to conquer every market that he could. In addition, the West Coast of California, far flung from Indianapolis though it was, was a hotbed of early automobile racing, and of men who loved big, fast cars and who had the money to own them.

Sales and racing of Stutzes west of the Missisissippi was handled by one Walter Brown, a dealer based out of Santa Monica, who established a Los Angeles-based team of Stutzes in September 1911. Surviving advertisements from The Los Angeles Times indicate that Stutzes were first raced in California at about that time, and they featured the original Wisconsin T-head design of 4¾-inch bore and 5-inch stroke, which would be utilized only on the 1912 Model A.

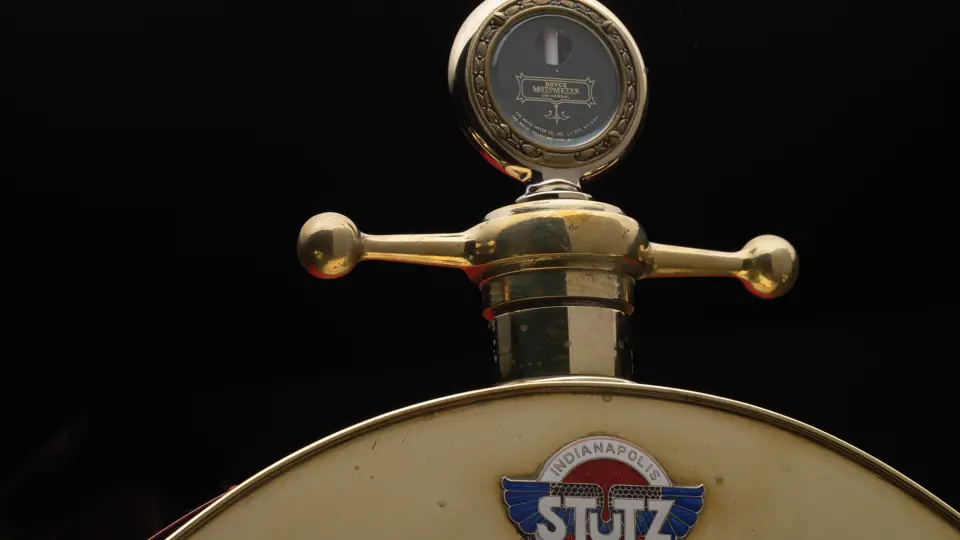

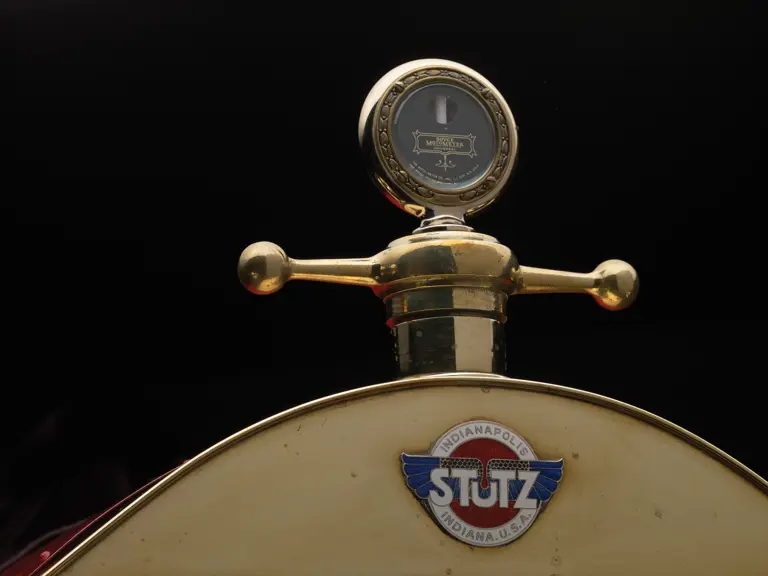

The car offered here was discovered in California in 1949, and it is, in all likelihood, one of those brought west by Brown. The Wisconsin Engine Company wrote to an earlier owner of the car, in a letter which is on file, and they described this engine, number A730, as having been built for Stutz in late 1910; thus, it found its way into one of the first 1912 models built in late 1911. In addition, this car’s radiator, which has a core appearing to be “sectioned,” is also unique to the very earliest 1912 cars. The chassis beneath shows modifications made only to the Bear Cat model, confirming that this was originally a Bear Cat when delivered from the factory. Combined with the very early engine number, this lends credence to the belief that this is one of the earliest Bear Cats built, if not a prototype.

When found, it had a later gas tank and racing seats fitted, according to noted racing historian Joe Freeman, and the car had no evidence of the double Hartford shock absorbers that were installed on the factory racers; as such, Brown likely delivered this car as a standard Bear Cat, and it was privately entered in events by an original or early owner. It may never have been used as a “street car” when new.

The Bear Cat was sold in 1949, in solid, complete “as-raced” condition, by Earl Jones, of Seal Cove, California, to two brothers in Massachusetts. Fortunately, the brothers did little with the car, and after their passing some four decades later, it was acquired by noted enthusiasts Charles LeMaitre and Arthur Smith. Photographs of the car as they received it show it to be an unmolested racing car, still with its racing tank and seats fitted, and it was very complete.

Mr. LeMaitre performed extensive research into the car’s history with the Harrah library at the National Automobile Museum, as well as with experts such as Joe Freeman, correspondence with whom is included in the file, discussing the car’s possible early racing origins. In fact, legendary Stutz guru A.K. Miller stated to Mr. LeMaitre that this was an original race car. It was during this time that the car’s heritage as an original, California-delivery Bear Cat were confirmed, with the original Golden State registration number still evident, as originally painted on the car’s radiator core. This original radiator has been preserved, and it accompanies this automobile today.

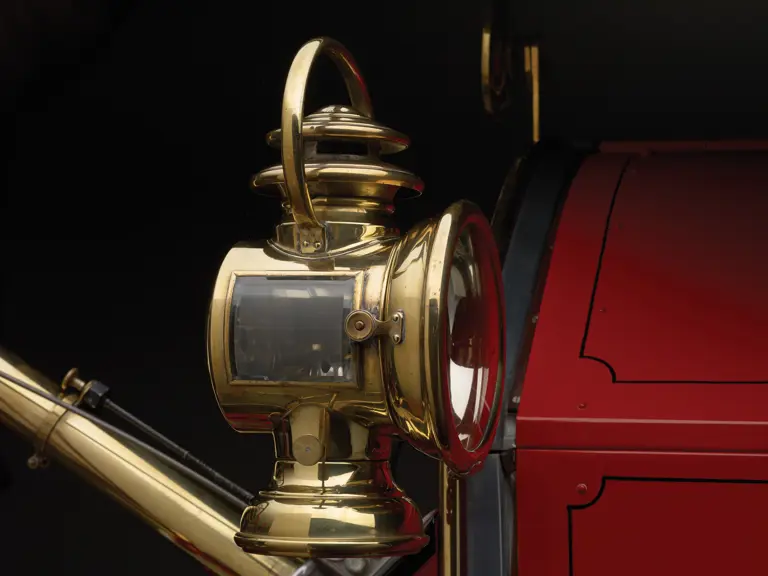

The car was eventually passed to another noted New England collector, who undertook a no-expense-spared, frame-off restoration. The engine was rebuilt by Brass Era guru David Greenlees to extremely close tolerances, with expert machine work in the course of a total rebuild, ensuring not only that every component of the car would be as-original, but also that it would be durable and long-lasting for continued road use. Final assembly and detailing were in the owner’s private shop, with paintwork performed by noted Bugatti restorer Scott Sargent, of Vermont. Exhaustive work went into sourcing correct lamps and trim, to return the Stutz to as near as possible to its original delivery form. Receipts and letters from the hunt, as well as many photos of the car before and during its restoration, are available for inspection.

An expert in early cars, who has had the opportunity to drive it, reports, “The car is delightfully agile and extremely powerful; the steering is light, the brakes are particularly adequate for a car of this nature, and the overall operation is very user-friendly, with a hidden electric starter installed during restoration. The gearing is perfection, as the torque curves are matched impeccably by its transmission ratios. For guys who love driving these early high-horsepower Brass Era cars, this Stutz makes the T-head Mercer seem like child’s play.”

Recognized by Stutz enthusiasts as a genuine Bear Cat, and as an excellent example of the marque, this car’s offering here represents the first time in many years that a true and particularly early Bear Cat has been available. This is the first time that this particular automobile has ever been offered publicly, and it is a very significant opportunity. The excitement of the moment is palpable, and it recalls the thrill that the Bear Cat unleashed upon the world in the early years of motoring.

It is about the engine that starts with a growl and hustles to speed with a steady, ceaseless drumbeat. It is about exhaust that crackles through its open pipe like a roaring autumn campfire. It is about easily experiencing speeds above 70 mph on an open chassis aimed towards the west wind. It is automotive performance art at its most visceral and soul-stirring.

| New York, New York

| New York, New York