1911 Mercer Type 35R Raceabout

{{lr.item.text}}

$2,530,000 USD | Sold

{{bidding.lot.reserveStatusFormatted}}

- Ex-Henry Austin Clark Jr.; single-family ownership since 1949

- Formerly owned by racing driver William C. Spear

- The earliest extant 1911 T-head Mercer

- Outstanding patina that dates to World War II

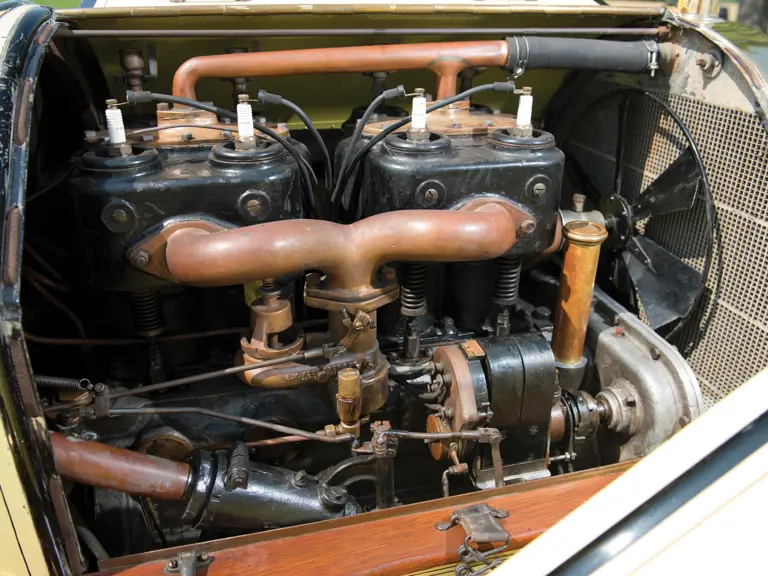

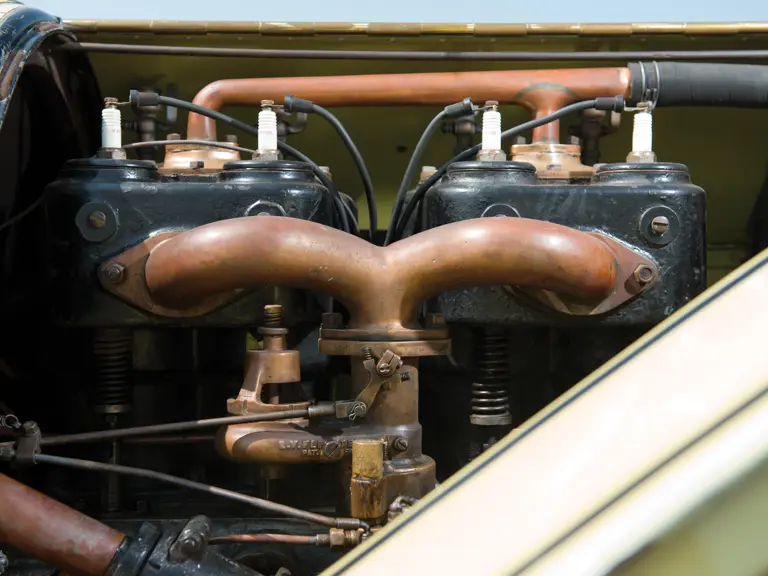

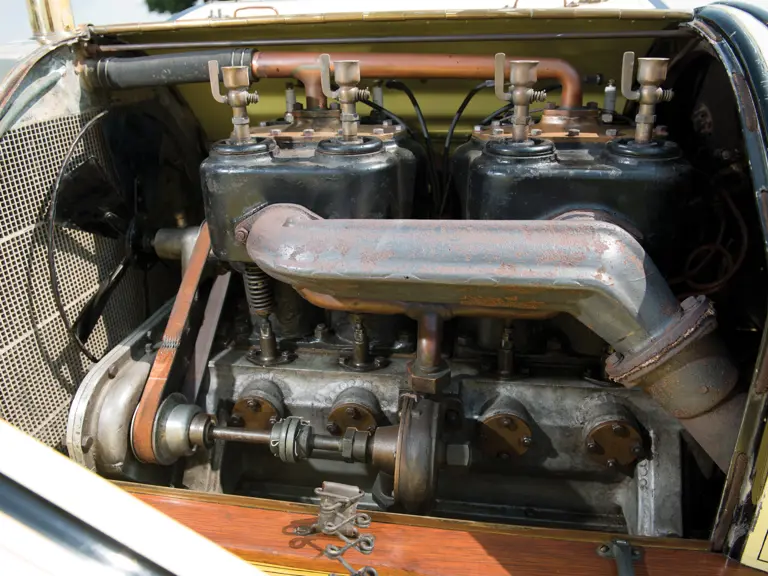

301 cu. in. T-head four-cylinder engine, three-speed manual transmission, solid front axle with live rear axle, and two-wheel rear mechanical drum brakes with a foot-operated transmission brake. Wheelbase: 108 in.

The Mercer Automobile Company was established in 1909 by the Roebling family, creators of tensioned wire rope suspension bridges, embodied by the Roebling-built Brooklyn Bridge. The company was crippled early on by the deaths of its Roebling family leaders, but it survived until 1925, when it was renamed the Mercer Motors Company, signaling its acquisition by Hare’s Motors, a joint venture with Simplex and Locomobile. During that short early period, however, it was responsible for one supremely important, successful, and significant automobile.

The Mercer Type 35R Raceabout defined the concept of “sports car” long before it became a common description. The T-head-powered Type 35R was recognized from its introduction for elemental appearance, ample power, and, most importantly, the hard to define but easy to recognize attribute of “balance.” It won races and the hearts and admiration of sporting drivers from its inception.

Few automobiles can claim the distinction of having remained valuable throughout their histories. The Mercer Type 35R is one of them, as they have always had appreciative long-term owners, in whose hands their combination of style and performance have been carefully preserved and they have been frequently and enthusiastically exercised.

Owning a Mercer Type 35R has rarely been about starched shirts, manicured lawns, champagne receptions, perfect paint, and brilliant brass. These superlative machines are more likely to see gravel roads, dirt ovals, road circuits, and high-speed tours. But the highest-profile collections of the most serious, informed, and discerning automobile enthusiasts contain, or aspire to contain, an example, as a Mercer is an essential element in the automobile's history and a source of a limitless supply of driving endorphins. The example offered here, 1911 Mercer Type 35R chassis number 35-R-354, engine number 35-R-137, exemplifies all those attributes.

Not only is it ready to take to the roads of the Monterey Peninsula, but it is also coming from the family of the foremost early collector and scholar of automobile history, Henry Austin Clark Jr., combining the Mercer driving experience with singular provenance in the hands of one of automotive history’s best-known and most-loved characters.

MERCER TYPE 35R EVOLUTION

The Roeblings were always looking for new technical and commercial opportunities, as the wire rope business was starting to become more competitive and less profitable, and they approached the automobile as an engineering puzzle. Determined to build a quality, high-performance automobile, they proceeded carefully and empirically.

At the instigation of Washington A. Roebling II, the grandson of company patriarch John A. Roebling, the family's budding enterprise learned by association with like-minded pioneers, eventually assimilating the best ideas of the Étienne Planche-designed Roebling-Planche, William Walter’s Walter automobile, and the short-lived but promising Sharp-Arrow of William and Fred Sharp to form the basis of the first Mercer automobile, which was introduced in 1910 and powered by a four-cylinder L-head Beaver engine.

That same year, the Roeblings and their commercial partners from the Kuser family added the final element required to complete the Model 35R when they hired self-taught designer Finley Robertson Porter. Both Washington Roebling and Finley Porter espoused racing as a way to demonstrate their automobile’s capability and cement the Mercer’s identity into the public's consciousness.

In the Roebling-Planche and Sharp-Arrow Runabouts, Mercer had the basis for the lightweight live axle, leaf-spring, shaft-drive chassis it needed, but they were powered by purchased engines. The remaining element was its own better engine, which would complement the chassis and give Roebling and Porter the high-performance, competitive automobile they both wanted. The Mercer Type 35R was the result, and it more than met its constructors’ goals.

THE MERCER TYPE 35R

With the Mercer Type 35R, Porter took a substantially different approach from competitors who resorted to larger and larger displacement engines, relying on brute force to achieve the power to be competitive. Porter relied on the superior breathing of cross-flow porting to squeeze power from a smaller engine. According to noted Mercer authority Fred Hoch, Porter’s T-head combustion chamber ran reliably and produced unprecedented power, with a compression ratio of 6.5:1, while most contemporary engines were 4.5:1 or less.

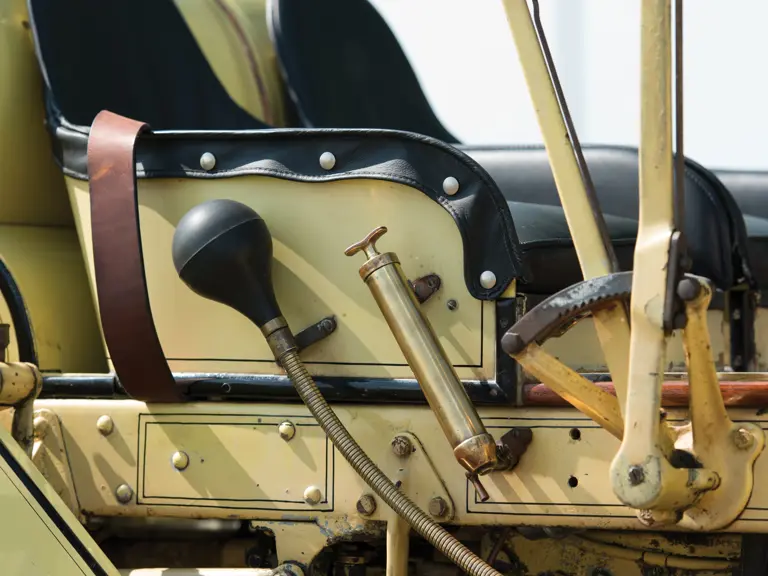

This is the simplest of automobiles, as it had just four cylinders with a 4⅜-inch bore and 5-inch stroke, for a total displacement of just 301 cubic inches, or five liters. Blocks were cast in pairs and mounted on an aluminum crankcase, in T-head configuration, with intake valves on the right and exhaust valves on the left. In 1911, ignition was supplied by a Bosch high-tension magneto, with fuel supplied by a single Fletcher updraft carburetor. The engine was mated to a three-speed selective transmission with a multi-disc clutch, and the whole setup was mounted on a chassis with live axles and a mere 108-inch wheelbase. Stopping this machine was accomplished with a mechanical driveshaft foot brake and hand-operated mechanical rear-wheel brakes.

Although the Mercer sales catalogue acknowledged the rating at just 30.6 ALAM horsepower, it also stated that the actual output of the Type 35R was a minimum of 58 brake horsepower at 1,700 rpm. When analyzing the performance of the Raceabout, correspondence between Bill Harrah and Austie Clark in 1958 substantiates that there was no specialized Raceabout engine block, although experts acknowledge that the bore for the 35R is a slightly smaller 4⅜ inch, compared to the 4½ inch used on other models later on.

Simple is frequently very good, and the Mercer T-head Type 35R is very good indeed. It could be driven from a dealer's showroom straight to the starting line of any race of its day, commit itself with honor, frequently with laurels, and then be driven home for a leisurely Sunday tour. The Mercer Type 35R’s concept is best described by Finley Porter’s observation years later in an interview with Henry Austin Clark Jr., which was published in the program of the 1952 New York Motor Sports Show, where he stated, “We sold racing cars to the public.”

Mercer entered two Type 35Rs in the first 500-mile race at Indianapolis. Aside from three 284-cubic inch Cases, none of which finished the race, the Mercers were the smallest engines in the field, barely half the size of the 597-cubic inch Simplexes. Yet, both Mercers finished, with Hughie Hughes covering all 200 laps in 12th place and Charles Bigelow, who had brought Mercer its first win in the Panama Pacific Light Car race in San Francisco in February, flagged home in 15th.

It is said that Hughes and Bigelow then remounted the Mercers’ lights and fenders and drove them back to Trenton—a feat that took place on the rudimentary tracks that passed for roads between cities of the time and may be as formidable as beating Howdy Wilcox's 589-cubic inch National or the 520-cubic inch Benz of Bob Burman.

Famed drivers of the day flocked to Mercer, endorsing its qualities with their illustrious names, such as Caleb Bragg, Barney Oldfield, and Ralph DePalma, and filling record books with wins. Austie Clark in one of his “Young Nuts and Old Bolts” columns in Old Cars Weekly recounts some of the Mercer Type 35R’s other important triumphs: 1st and 2nd in the 1911 Light Car Race at Elgin, backed up by a 3rd place in the later Big Car Race; 1st and 2nd at Fairmount Park in Philadelphia; a highly publicized winner of the Savannah Challenge Trophy; Ralph DePalma’s 300-inch class win at Santa Monica on May 4, 1912, backed up by eight new speedway records the following day; and Spencer Wishart’s 200-mile victory at Columbus, reportedly in a Mercer fresh off a dealer’s showroom floor. Although, there was no Mercer dealer in Columbus, and the car was probably fresh off of a railroad flatcar from Trenton, not that it made much difference.

As noted by respected collector George Wingard in his Wolves In Sheep’s Clothing, “Many of the Mercer wins during 1911 and 1912 were, however, documented ‘stock Raceabouts’ by the AAA Contest Board. It would seem that 1911 would probably have been the most likely year for ‘stock car’ wins, and in that year, Mercer Raceabouts captured an unprecedented number of first-place wins.” If anything, the racing accomplishments of the Mercer were understated, as there were many events held on dirt tracks that were not AAA-sanctioned; therefore, the surviving record of results is incomplete.

As strong as their performances were, it was ordinary, if wealthy, buyers to whom the Mercer Type 35R appealed, as it was a car that could be bought, driven straight to a race track, and, with or without its road equipment, driven to a strong placing, if not outright victory. It was this ability to be a winner in the hands of top drivers and competitive even in the hands of amateurs that made the Mercer Type 35R a legend.

Finley Porter left Mercer at the end of the Roebling family's management in 1914. Production through that year and the end of Finley Robertson's T-head engine is approximated by the Mercer Associates at around 1,830 cars. Of those, they believe that fewer than a quarter of these were Raceabout models, with only eight 1911 Mercers known to exist. This survival rate over the intervening century is nothing short of amazing, especially in light of in-period racing, road accidents, and wartime scrap drives.

CHASSIS 35-R-354

According to the 1913 New England Auto List, chassis 354 was owned by Frank L. Coes, of Worcester, Massachusetts, with an address at 2 Coes Square. The Coes family owned a prominent and successful company that made hand tools, and it was successful enough that Coes owned both the Mercer, likely from new, and an American touring car. That Frank Coes was a man of diverse interests is evident from a newspaper report in the Daily Boston Globe on June 7, 1930, which reports “the discovery of a $35,000 beer brewing plant in the basement of the Coes Wrench Company plant at Coes sq [sic].” Charges against Coes were dismissed three weeks later, “on a technicality,” according to another Daily Boston Globe article on June 27, which featured the U.S. Commissioner's observation “that he saw no other way than to discharge Mr. Coes, but morally he could not see why Mr. Coes did not know what was going on in the basement of his factory and his office only 10 feet away from the place.”

The Mercer eventually found its way into the hands of another New Englander, William C. Spear Jr., the scion of a prominent Manchester, New Hampshire, family. Spear owned an estimable collection of quality antique automobiles in the late ’30s and early ’50s, including a Curved Dash Olds, a 1904 Mercedes, a 1907 Packard, a 1910 Simplex, a 1913 Silver Ghost, both a 1917 and 1918 Pierce-Arrow, and a 1930 Bentley. He acquired the Mercer Type 35R sometime during the war years and commissioned Hyde Ballard to convert it from Runabout to Raceabout form, which he undertook from 1945 to 1946. Both body styles had the same wheelbase, running gear, brakes, and driveline, making the conversion a relatively simple task of removing the wraparound cowl and lowering the seats and, consequently, the steering wheel rake. The completed car was debuted by Spear at the Spring AACA Meet held at Beaver College, Pennsylvania, in May 1947.

Bill Spear contracted the sports car racing bug in the late ’40s, quickly becoming a Ferrari owner and driver of note, despite the disadvantage of his 6'4", 240-pound frame. He finished 3rd in the first Sebring race in his Ferrari 166MM (s/n 0054M), driving with George Roberts, and he became a SCCA C Modified National Champion in 1953.

His Ferraris, all six of them, along with Aston Martins, Maseratis, and other marques, were maintained in Alfred Momo's shop in Queens, New York, alongside Briggs Cunningham's equipe, and a congenial relationship among Spear, Cunningham, John Fitch, Walt Hansgen, Phil Walters, Jim Kimberley, and other leaders in early post-war American sports car racing ensued. Spear managed the Cunningham team at Le Mans in 1950 and then drove for Cunningham at La Sarthe three times, finishing 3rd overall in 1954, when he drove the Cunningham C-4R with Sherwood Johnson.

Spear joined the Antique Automobile Club of America in 1944, and in 1947, the club published a roster of members and their cars, which included 24 Mercers. Seventeen of them were the pre-1915 Finley Robertson Porter T-heads, and of those, 15 were Raceabouts or Runabouts. Among them, some owners should need no introduction. In addition to Bill Spear, they included Hyde Ballard, David Uihlein, Alec Ulmann, and tenor James Melton. Interestingly, it would not be until years later that the rosters, assembled by the enthusiast club known as the Mercer Associates, would identify this car as the earliest known 1911 T-head Mercer in existence.

As this chapter in Spear's life began to unfold, his Mercer suffered rear axle maladies and was sent to legendary New York City mechanic Charles Stich for repairs. Time went on, Spear's interests were gravitating towards post-war sports cars, and eventually the opportunity arose for the Mercer's penultimate owner, Henry Austin Clark Jr., to enter its history.

HENRY AUSTIN CLARK JR.

Henry Austin “Austie” Clark Jr.'s life might be characterized by a series of humorous vignettes, but behind the parties and adventures resided the greatest automobile historian of all time, a man for whom no automobile was beneath consideration and whose voracious and acquisitive scholarship led to assembling the greatest single collection of automobile literature and documentation ever amassed.

Austie began his automobile fascination at an early age, fondly remembering the 1916 Packard Twin Six of his father’s, whose interests in the Cuban-American Sugar Company provided the family's wherewithal.

Austie was a man of incredibly generous and accepting spirit, whose contributions to the automobile included cooperating with Bruce Wennerstrom to save the Madison Avenue Sports Car Driving and Chowder Society, helping organize the Bridgehampton Road Races, helping finance the Bridgehampton Road Racing Circuit, leading the rejuvenation of the Glidden Tour, heading at one time or another most of the clubs devoted to preserving old automobiles, from the VMCCA to the Friends of Ancient Road Transportation, and serving as the research director for Automobile Quarterly.

As his literature collection grew, he became the resource for collectors seeking obscure information, never failing to answer the telephone, even during family dinners, and dispensing facts from his vast knowledge, backed up by his unequaled collection of original manuals, brochures, periodicals, and literature. If among the horde there was a duplicate brochure or manual, and there often was, it was usually promptly dispatched by mail to encourage the enquirer.

The collection grew so large that it eventually required an addition to the family home in Glen Cove, where Austie lived with his wife, Waleta, aka “Wally,” and their four children, Ann, Jim, Hal, and Cynthia.

Documentation and cars were only part of Austie’s acquisitions. Walls, shelves, and cabinets were filled with automobiling ephemera, including brass lights, bulb horns, mirrors, tools, tour guides, tire pumps, and so much more. Automotive art, then unknown as a genre, appealed to Austie’s aesthetics.

He established the Long Island Automotive Museum in the outskirts of Southampton, Long Island, off the Sunrise Highway. It soon became a focal point for the sometimes boisterous gatherings of auto enthusiasts, which ranged from cartoonist Charles Addams to Alec Ulmann. Friends helped him carve out a dirt track through the woods behind the triple Quonset Museum structure and build a series of sheds that grew along with the collection of cars—from orphans to Classics—that found refuge in Austie's care. The dirt track, known as the “Wilderness Road,” served as a road for museum visitors’ demonstration runs and fire engine rides and the playground for the Clark children, where they learned to drive long before they were old enough for public roads.

There were many prizes in the Long Island Automotive Museum, not least the Mercer Type 35R, which was always a draw for spectators. Austie, an avid photographer (“of old cars and young girls,” according to his business card), enjoyed photographing celebrities in it, but no period photo of the Mercer is as evocative as several taken with Finley Robertson Porter, its designer, behind the wheel. Porter had retired to a home in Southampton, across the street from one of Austie's favorite haunts, Herb McCarthy's Bowden Square, and he frequently enjoyed Austie's hospitality at the museum.

Being outside the limits of the Southampton Volunteer Fire Department's coverage area presented a problem in maintaining insurance coverage. Austie solved it by creating the Sandy Hollow Fire Department, which was made up of working antique fire trucks, starting with the American LaFrance Hook and Ladder donated by Southampton on the day the museum opened. Austie was the chief, but anyone he liked might be awarded the rank of captain, which was accompanied by an appropriate badge.

The museum was a great success in preserving automotive history and serving as a gathering point for auto enthusiasts, but the repeated threat of the widening Sunrise Highway caused Austie to reconsider the fate of his four-wheeled treasures. Thus, in June 1963, the first of a series of three auctions was held to deaccession the collection, with subsequent sales taking place in 1972 and 1978. With Austie in charge, the auctions were themselves demonstrations of his attitude and generosity, more directed toward finding good homes for his automobiles than to realizing the maximum return.

When he heard that a Long Island volunteer fire department wanted to reacquire a piece of apparatus that he had bought years before, and when he learned how much money they had raised from cookouts and bake sales, he dropped the hammer on their bid at that amount, raising the ire of others who had been prepared to pay more for it. He likewise made sure two Canadians who had trekked down from the Maritimes in the hope of acquiring a Brighton-eligible 1903 Olds project went home with it at the price they could afford.

His collection of automotive history was deeded to The Henry Ford during Austie's lifetime, with the proviso that it remain in Glen Cove as long as he needed it. When the collection was finally transferred, the contents weighed 54,000 pounds and filled three moving trucks. Henry Austin Clark Jr. preserved not only irreplaceable automobiles and the records that today still support restorations and automotive scholarship at The Henry Ford, but he also fostered the sense of friendship, mutual support, and enjoyment that preserved the value and appreciation of old cars. His stewardship of the history of the automobile, the automobile industry, and the people who have created and preserved it cannot be overstated.

WHILE THRONGS OF VEHICLES CAME AND WENT, THE MERCER STAYED

Back to the Mercer, which was sitting in Charlie Stich's New York City workshop, awaiting final reconciliation for its rear axle repairs. Bill Spear's interests had turned toward Sebring, Le Mans, and Maranello, and Henry Austin Clark Jr. was able to acquire it in April 1949 for $3,500, which included settling the $150 balance of Stich's $650 bill, a copy of which is included in the car’s file. It was subsequently fettled by Ralph Buckley in Austie's style of attractive but not overdone appearance and full functionality, and it assumed a central role in his activities. Despite the alternatives of two Simplexes, a Speed car and a Toy Tonneau, and a plethora of others, including the famous New York to Paris-winning Thomas Flyer, it was one of his favorite and most popular drivers. Due to his early experience and admiration of the car, it is no surprise that when given the opportunity to choose one car for himself, Austie’s son, Hal, picked the Mercer, and it remained at the museum until its closing, whereupon it was moved to Connecticut.

Hal is effusive in his praise for the Mercer, which he succinctly describes as “the best driving of all the antique cars by a long shot.” His evaluation of its appeal is largely based on its simplicity and fitness for its purpose. “You're totally exposed to the elements—wind blows through everything. To the passenger, it feels like being on a race horse. There is this wonderful sound, and it grips the road and handles corners unbelievably. The steering is precise; the fenders flap like butterfly wings—you're out there in the elements with a car that does everything you'd want a race car to do. It is so simple, appealing in its less is-more, bare essentials nature.”

In Old Cars Weekly, Austie Clark identified nearly the same distinctions, “No other car of the day, even ones with much larger engines, could run away from a well-tuned T-head Mercer…The steering is precise and accurate. The car would not turn better if it were on railroad tracks…Shifting back and forth between the top two gears…is done instantly and without the need of double-clutching.” That is a sentiment that has been echoed again and again by people who appreciate good design in pursuit of well-defined purpose for over a century. As it is low, sleek, and refined, there is nothing superfluous to the performance and handling on this Mercer Type 35R Raceabout. It was built by one of the most accomplished engineering families of the late 19th and early 20th centuries, the Roeblings, and was victorious in uncountable speed contests, where it was driven by both professionals and amateurs. The Mercer Type 35R Raceabout is one of a kind and a car which Austie described as “without doubt, the greatest pre-war car built in the United States.”

This particular 1911 Mercer Type 35R is immeasurably enhanced by its provenance in the hands of Henry Austin Clark Jr. and his family for 65 years. It is the legacy of not only Finley Robertson Porter and the Roeblings but also the man who more than any other defined the stewardship of automotive history and the individuals who engaged in automotive manufacture.

This 1911 Mercer, which was acquired in 1949, was among the first in a succession of great pre-war cars owned by Henry Austin Clark Jr., and it is the one that has been retained the longest. It proudly displays its 1940s patina, yet it is freshly serviced and prepared, and it is ready to resume its appointed purpose of thrilling its driver, passengers, and onlookers, while also perpetuating the legacy and memory of a unique, caring, and generous figure that is known instantly by his nickname, “Austie.”

He was a character, nowhere more apparent than in the photograph here, which shows him at the wheel of the Mercer, sliding through a cloud of dust, smiling gleefully under a preposterous cap, and peering through a pair of ridiculously oversized scuba goggles. Mercer and man are one: singular, unique, and boisterous.

| Monterey, California

| Monterey, California