114 hp, 202 cu in L-head six-cylinder engine, twin two-barrel Carter carburetors, three-speed manual transmission with overdrive, independent front suspension with coil springs and unequal length A-arms, live rear axle with semi-elliptic leaf springs, and four-wheel hydraulic drum brakes. Wheelbase: 105"

• One of only 25 built by Carrozzeria Touring in Milan

• Correctly restored in original cream paint with red/white interior

• Powered by Hudson Jet six with three-speed transmission

Hudson set the U.S. auto industry on its ear in 1948 with the introduction of the streamlined “step-down” range. One of the first cars to be advertised on television, the new model was only 60-inches high and had a very low center of gravity. The Pacemaker, Super, and Commodore range was expanded to include the famous 308-cubic inch Hornet in 1951, which would dominate NASCAR so thoroughly—winning 40 of 48 stock car races in 1952—that it would eventually be banned. The basic shape of the step-down Hudsons endured for six years, until 1954, when the company merged with Nash to form American Motors.

Just before that distressing bear-hug merger occurred, Hudson designer Bill Spring contracted with Carrozzeria Touring, of Milan, to produce a dream car, in the same way that Virgil Exner had convinced Chrysler to partner with Ghia. That union produced a handsome series of sports coupes, including the Thomas Special, DeSoto Adventurer, and Dodge Firearrow. Spring sent complete Hudson Jet compact sedans to Milan, and Touring cut off the bodies and created a superleggera coupe, with aluminum panels over a tube steel frame. The result was 10-inches lower than the Jet and bristled with innovations, including a wrap-around windshield and Abarth-style air vents above the headlights and in the rear fenders, to aid brake cooling. Spring designed doors cut seven inches into the roof for ease of entrance, which he had pioneered when working for coachbuilder Murphy in the 1930s.

Eminent stylist Strother McMinn worked at Hudson for a while and recalled that the Italia’s seats were never duplicated by any other car maker. They were twin reclining bucket seats with two separate backrests and used different densities of foam for the bolsters to give better support. Spring designed the seats to be firmer at the lower back than the upper. Between the two cushions was air space, and the seats actually “breathed” through the motion of the passengers.

The car rode on Borrani wire wheels and had a distinctive oval grille, with an inverted “V” in the front bumper as a Hudson cue. Less successful were the triple exhaust pipes in the rear fenders, which actually housed stop, tail, and turn signal lights. Leather seatbelts were standard, but since they were attached to the seats, their safety value was doubtful.

The Italia was designed as a fast two-seater, with provision for a good deal of luggage—a real Italian “gran turismo”—and there was talk of entering the American Stock Class of the Mexican La Carrera road race, which Lincoln had won in 1952. Perhaps with that race in mind, Hudson ordered the minimum required 25 cars from Touring for homologation on September 23, 1953.

Compared to other production dream cars, the price and performance numbers were not encouraging. At $4,800, the Italia was more expensive than the $4,721 Nash-Healey and much more costly than the $3,668 Kaiser Darrin or the $3,523 Chevrolet Corvette.

Dealers took orders for 19 Italias in the fall of 1953, but the 1954 merger with Hudson put paid to the idea of any more examples beyond the one prototype and 25 initial cars. Would-be buyers reported unsuccessful attempts to purchase Italias from dealers, even with full payment up front, but it seemed clear that the management of the new American Motors Corporation intended the program to go no further. Further problems ensued when Touring refused to supply any spare parts, including such important items as taillights and trim. Roy Chapin, who later became board chairman of AMC, was the sales manager for the Italia program and was ordered to “get rid of those cars,” which he did.

The car on offer today is one of 21 Italias believed to have survived. Restored about four years ago, this coupe has the correct red and white leather and vinyl interior and is finished in Cigarette Cream, the color in which most Italias were painted. The brightwork and trim is excellent, and the car rides on the correct chrome wire wheels. It is accompanied by a comprehensive file of documents and is said to run and drive very well.

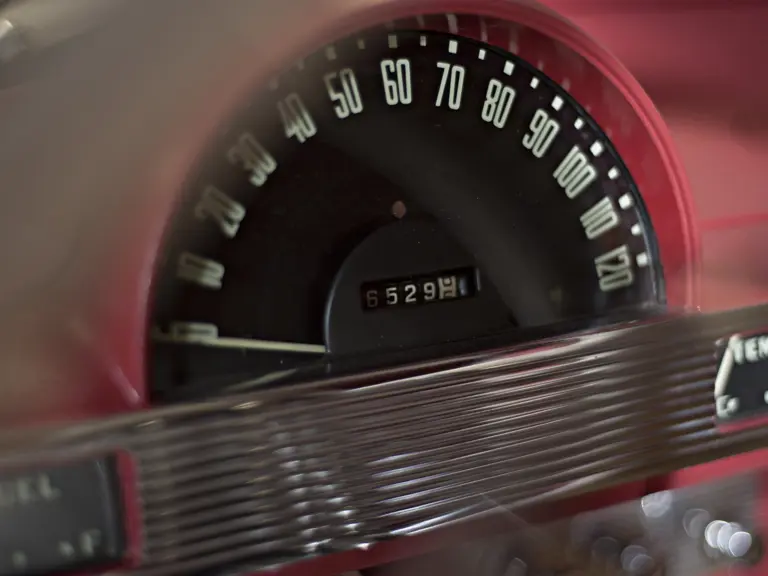

Factory data indicates that the 1954 Italias were numbered IT100001 to IT100009, with the remaining examples numbered IT100010–IT1000025 and being registered as 1955 models, making this the second 1955 Italia to be built. It is rumored to have been purchased new by Liberace, whose flamboyance it would certainly have complemented, but no documentary evidence can be found to support this. The odometer indicates 66,529 miles, and the owner says that the car’s general condition suggests that this is likely to be the original mileage.

The Hudson Italia is far less common than the contemporary Kaiser Darrin or Nash-Healey, of which several hundred were produced. In many respects, these other two sports cars seem much more mainstream than Frank Spring’s creation, which is a remarkable concoction of fantasy and practicality and is guaranteed to draw a crowd wherever it appears.

| Monterey, California

| Monterey, California