Winton’s early years can be summed up in one word: competition. Having demonstrated the reliability of his car with a 47-hour dash from his native Cleveland to New York City in 1899, Alexander Winton entered a single-cylinder racer in the 1900 Gordon Bennett Cup race in France. Although sidelined by wheel failure, Winton’s entry made history as the first American car to compete in a European race.

A glutton for long-distance journeys, Alexander Winton made another New York trip in November to exhibit at the first automobile show. He drove a prototype of his single-cylinder 1901 model, while most of his display cars were shipped by rail. At the show, the mud-spattered car was on the Winton stand with the notice that he had bettered his time by nine hours from the year before.

The first Winton Bullet, a four-cylinder, 57-horsepower racer, was built in 1902. Winton broke his own speed record with it at Cleveland’s Glenville track, setting a new mark of 55.38 mph. A match race at Grosse Pointe, Michigan, however, against Henry Ford’s 999 with Barney Oldfield at the wheel, was less successful, as Winton dropped out with ignition trouble.

The Winton long-distance saga really hit its stride with what filmmaker Ken Burns celebrated as “Horatio’s Drive.” On 23 May 1903, Dr. Horatio Nelson Jackson and Sewall K. Crocker left San Francisco in a 20-horsepower Winton twin bound for New York. Their ordeal was arduous, requiring many repairs to the car, detours to find passable roads and ingenuity to find supplies. Against all odds, they reached their destination 63 days later, having made America’s first transcontinental journey by automobile.

Winton contested the Gordon Bennett again in 1903, with a pair of eight-cylinder Bullets. Beset with mechanical problems, both cars retired, and with them Alexander Winton as a racing driver. He did, however, maintain the racing team, and Barney Oldfield toured with the Bullets, setting records nearly everywhere he went. Oldfield and Winton developed differences of opinion in 1904, and parted ways in June. Winton replaced Oldfield with Earl Kiser, a Dayton, Ohio, native, who set yet another record at Glenville that August. The following year, Kiser had a bad accident in the Bullet. Thrown clear, he lost a leg in the aftermath. That spelled the end of Winton racing, but Kiser continued his career as manager of the Winton agency in Pittsburgh.

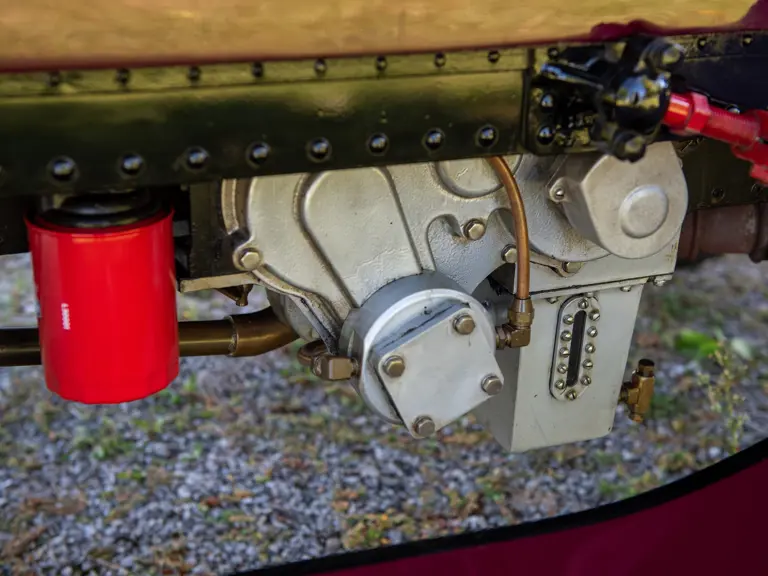

This 1904 Winton, among the last two-cylinder cars, has had its share of long-distance journeys. The consignor purchased it from a British owner who was able to have the car officially dated as 1904 for the annual London-to-Brighton Emancipation Run. Following engine trouble on the Run, it was returned to the United States and entrusted to Charlie Wake, a great-grandson of Alexander Winton. The engine rebuild was documented in a video as the work progressed. The owner then drove it from Indiana to the New York Adirondacks to commemorate Jackson and Crocker’s 1903 cross-country feat.

After the engine work was complete, Wake received a call from Edsel Ford III, Henry’s great grandson, challenging him to a re-enactment of the Grosse Pointe match race. Since the 1904 car was nothing like the car that competed against Ford’s 999, Ford Motor Company constructed two replicas for the reenactment instead.

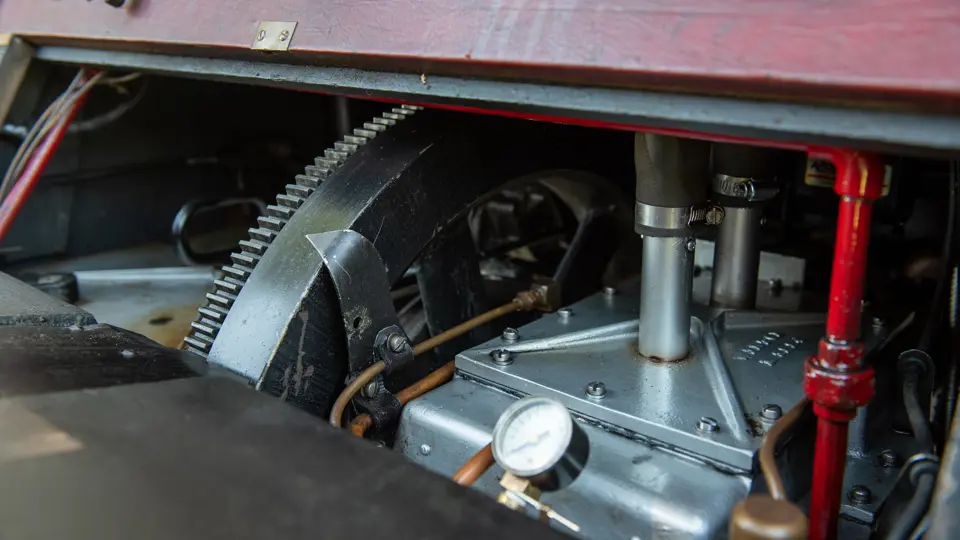

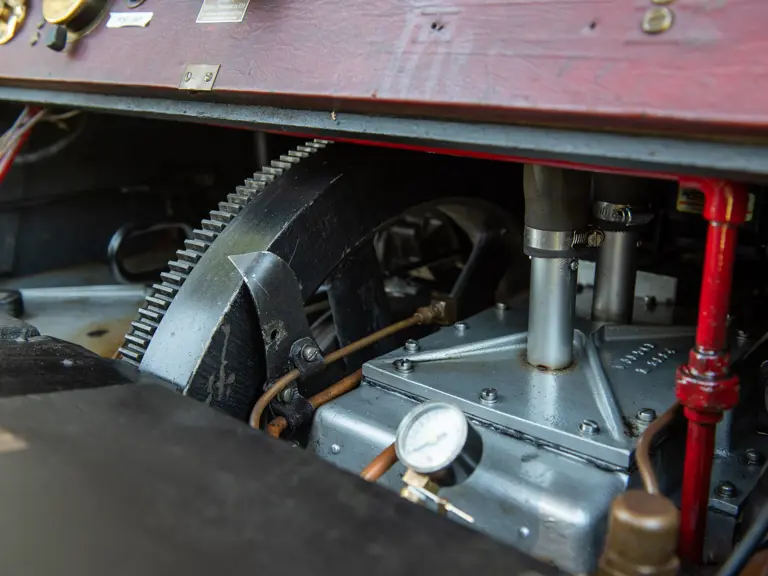

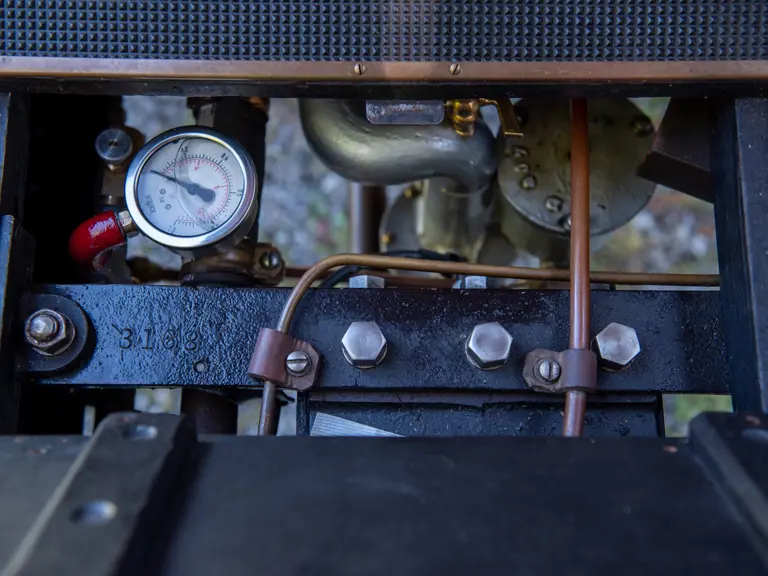

Finished in a bright magenta color, the Winton is spic and span from nose to tail. The seats are upholstered in matching buttoned leather, while a pyramid-pattern black rubber mat lines the floor. Instrumentation is minimal, comprising a 60-mph Jones speedometer (sans odometer) and a 30 psi Ashton pressure gauge, both in highly polished brass. A surrey top (albeit without fringe) provides shade and some weather protection, while a bulb horn at the driver’s right hand warns pedestrians and passers-by of the car’s approach.

Winton built fewer than 1,000 cars in 1904, so survivors are necessarily rare. This one is exceptionally fine and represents an uncommon opportunity to own a remarkable horseless carriage, eligible for the London-to-Brighton Run, no less.

| Hershey, Pennsylvania

| Hershey, Pennsylvania