1960 Chevrolet Corvette LM

{{lr.item.text}}

$758,500 USD | Sold

{{bidding.lot.reserveStatusFormatted}}

- One of the most historically significant Corvettes ever to be offered to the public

- One of three C1 Corvettes entered by Briggs Cunningham for the 1960 24 Hours of Le Mans

- Briggs Cunningham and Bill Kimberly’s car at Le Mans in #1 livery

- Extensively modified during subsequent ownership; rediscovered in 2012

This 1960 Chevrolet Corvette, chassis 3535, is a milestone of American motorsports history. As the #1 car run by American privateer Briggs Cunningham at the 1960 24 Hours of Le Mans, developed with clandestine assistance by a General Motors team under Corvette lead Zora Arkus-Duntov, it represents a crucial part of Cunningham’s final—and successful—effort to win the world’s most challenging race in an American car, with American drivers.

THE DUNTOV-CUNNINGHAM RACE EFFORTS

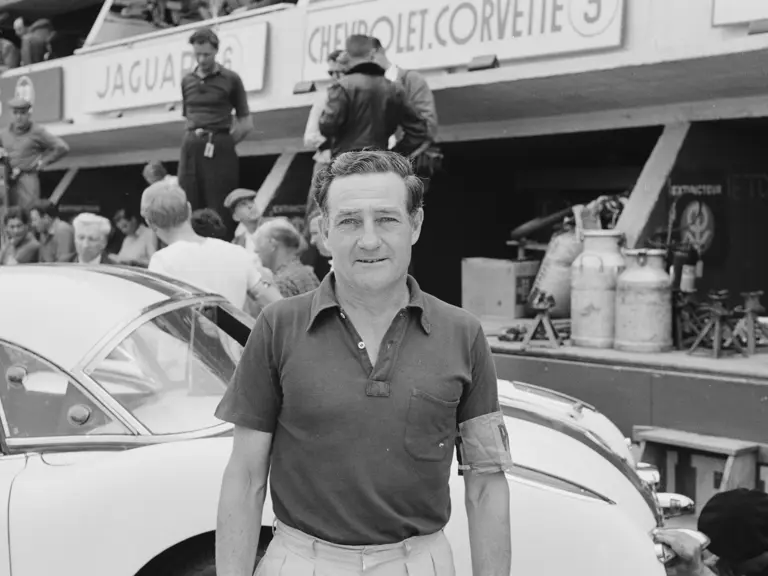

By the time he was approached by Zora Arkus-Duntov in the fall of 1959, American privateer Briggs Swift Cunningham II, heir to the Procter and Gamble fortune and entrepreneur, had all but given up on winning at Le Mans—an understandable conclusion after a decade of effort.

Well before the Ford Motor Company trained its sights on Ferrari, achieving a string of triumphs with its GT40 beginning in 1966, Cunningham had set out to conquer the 24-hour race. Such were his patriotic convictions that he took it upon himself to build an American car worthy of Le Mans, entering a pair of Cadillacs in 1950 and cars of his own making from 1951 to 1955—each hand-built in his West Palm Beach, Florida facility. Every year, Cunningham’s team drivers were, of course, exclusively American. As a wealthy and well-regarded sportsman, Cunningham enamored French crowds and the American public alike with his ambition, lavish spending, and extremely competitive nature.

Yet even as Cunningham triumphed in his other competitive pursuits, winning the 1958 America’s Cup race as the skipper of the yacht Columbia, success at the Circuit de la Sarthe eluded him.

Meanwhile, a team at GM had been at work developing a competition-spec car aimed at marquee endurance events such as Sebring, Daytona, and the crown jewel, Le Mans. This team was led by Ed Cole and managed by Arkus-Duntov with vehicle testing completed by some of the most notable American drivers of the time, including Cunningham. However, development was slow; the 1955 Le Mans disaster and changing sentiments about racing culminated in the Automobile Manufacturers Association racing ban, which prohibited all official American manufacturer racing programs effective 1 June 1957.

By late 1958, competitive undercurrents had surged, and development kicked off again—albeit supported by strictly unofficial agreements between manufacturers and privateer race teams. Negotiations with Cunningham completed on 7 January 1960, and by 19 January, Duntov’s team was already preparing a suite of bespoke racing engines to be dropped into the yet-to-be-acquired cars.

On 16 March, three similarly equipped Corvettes were sourced for Cunningham. To disguise Chevrolet’s involvement, all chassis were purchased via dealer Don Allen Midtown Chevrolet of New York City. Each chassis was specified with, quick-ratio steering, heavy-duty sintered-metallic brake linings, heavy-duty suspension, a close-ratio four-speed transmission, a Positraction limited-slip differential, radio delete, and temperature-controlled radiator fan.

The three chassis were further modified by Alfred Momo with Stewart Warner gauges, a Halibrand quick release fuel cap, Halibrand magnesium wheels, Firestone racing tires, Koni competition shock absorbers, Bendix fuel pumps (a primary and a back-up), an additional front sway bar, a 37-gallon fuel tank, additional ducting, two seats from a Douglas C-47 Skytrain aircraft, and a side-exit racing exhaust system. All three cars would later receive further modifications after additional testing, including changes to their rear axles, cylinder heads, engine internals—even magnesium hoods were specified but it is unconfirmed as to whether these were fitted to the trio.

Prior to Le Mans, the Cunningham cars benefitted from Chevrolet engineering and testing expertise (on a strictly unofficial basis, of course, at least in theory), leading to a constant stream of improvements to the chassis. This included pivotal development tests at Sebring and Daytona, at Bridgehampton Race Circuit in Sag Harbor, New York, and at the Circuit de la Sarthe in the months leading up to the 24-hour race.

If they were to have any hope of success at Le Mans, the Cunningham Corvettes needed on-track experience. This would come in the form of the 12 Hours of Sebring on 26 March, followed by a trial at Le Mans on 9 April. Though the team arrived at Sebring on 16 March, track marshals banished the entourage and their privateer racers to nearby Daytona for testing. Just two race engines had been completed for Cunningham by this time, and so he prepared two of his three cars for Sebring. One of the Corvettes was tested at Daytona; meanwhile, the other entrant was tested at Milford Proving Grounds before being sent down to Florida for the race.

Unfortunately, the 12 Hours of Sebring did not bode well for the team. Just 27 laps into the race, the #1 Corvette suffered a rear hub failure and was catapulted end over end, suffering major damage; thankfully, driver John Fitch escaped with only minor injuries. Some 14 laps later, the #2 Corvette, driven by Fred Windridge, experienced an engine failure, forcing another early retirement.

CHASSIS 3535 AT LE MANS

Undeterred by their disappointing outing at Sebring, the Cunningham team set to repairing the damage to chassis 2538 and outfitting the other two cars with rebuilt race engines and additional modifications gleaned from testing data.

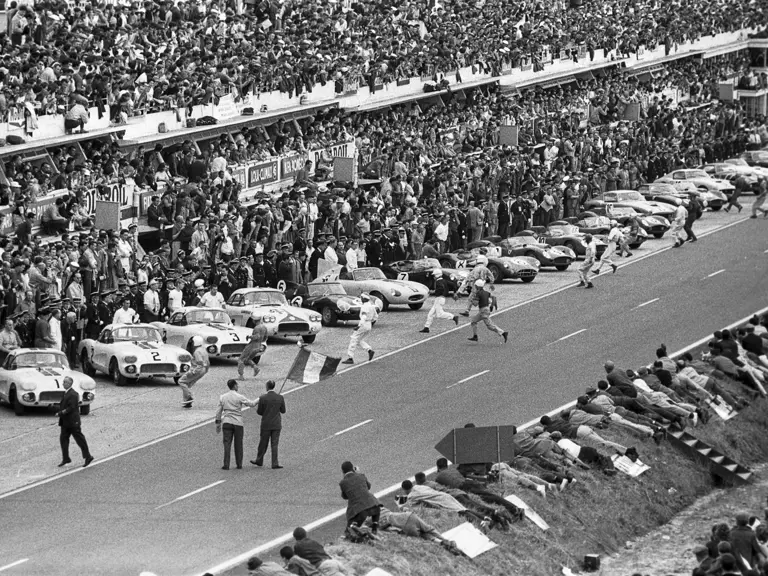

Four Corvettes arrived for preparations at Le Mans in early June, where they were assigned the numbers they would wear for the grueling 24-hour race: Cunningham’s #1 (3535, this car), #2 (4117), #3 (2538), and Camoradi Racing Team’s #4 (2272).

Interestingly, chassis 3535’s Le Mans registration papers, dated 25 May, show Duntov listed as a co-driver for the race with Cunningham. When Ed Cole found out, he came to a private agreement with Cunningham which conditioned GM’s continued unofficial support for the Le Mans effort, as well as Duntov’s trip to France, on Cunningham promising he would not allow Duntov behind the wheel for the race. Ed Cole knew Duntov was far too valuable of an asset to potentially lose in the dangerous 24-hour race, and Duntov had already raced at Le Mans four times between 1952 and 1955, supposedly on GM’s dime. While Duntov is documented as having been behind the wheel of a Corvette during several testing sessions, Cunningham kept his promise and Duntov was replaced by Bill Kimberly, an accomplished racer in his own right. Cunningham’s decision supposedly cost him his friendship with Duntov for fourteen years.

Car #1 began the race with Cunningham behind the wheel and together with the other two Cunningham Corvettes they appeared competitive against the European GT-5.0 field during the race’s opening hours. Around 6PM however, it started raining heavily forcing many to pit and make adjustments. It was during this time that #1 would make its first driver change. All fueled up, with new tires, and with fresh driver Bill Kimberly behind the wheel, #1 left the pits. Kimberly piloted the car swiftly through Dunlop, pushed the car to its limit down the Mulsanne Straight, and carefully took the turns at the Mulsanne Corner, Indianapolis, and Arnage. Kimberly was nearing the completion of his first lap when just after passing over the top of the hill after Arnage the car was met by a wall of rain. As Kimberly lifted off the power, he lost control of car #1 at the Maison Blanche corner, spun, flipped twice, and caught fire. Luckily for Kimberly the car landed right side up and he emerged from the crash unscathed. The fire melted the car’s engine ignition wires, causing 3535’s retirement after just 32 laps.

Shortly thereafter, a similar event forced the #2 car, driven by Thompson, off the track at the same corner, damaging the front and rear bodywork. Though #2 limped back to the pits and was repaired, a later engine failure during lap 207 forced another retirement for the Cunningham effort. The #3 Corvette piloted by Bob Grossman and John Fitch proved the most resilient of the Cunningham entries, winning the GT-5.0 class and finishing 8th overall.

AFTER LE MANS

After Le Mans, all three Cunningham Corvettes were brough back stateside and Momo returned the engines to Frank Burrell at GM. The three chassis were then passed along to Cunningham ally Bill Frick of Rockville Centre, New York, who proceeded to sell the cars in Florida. Unlike its brethren, chassis 3535 was immediately sold by Frick to another Cunningham friend, SCCA racer Marshall “Perry” Boswell Jr. of Delray Beach, Florida. Boswell received the car “as-raced,” save for the engine and hardtop; even the Le Mans roundel was still intact.

Historic imagery provided by the Boswell family presents illustrations of the chassis’ transformation from a beat-up, motorless race car to an extravagant, streamlined roadster. The front end was replaced with the single-headlight fenders of an earlier style, intersected by a unique Zagato-esque grille of Boswell’s design. The hood received a small, central scoop. The rear end remained largely intact, but the stock design’s distinctive side strakes were filled in. Finally, Boswell clad the whole chassis with black paint and perched it on chrome turbine wheels shod in wide whitewall tires.

At some point around 1966, Boswell sold the now-disguised ex-Le Mans racer. According to historical research on file, the car passed through several local owners—one of whom painted the car green, and then yellow—until arriving under the care of Jerry Moore in 1971. Moore sold the car in 1974 to Dan Mathis, and soon afterward the car disappeared from the public eye. It would remain out of sight for the next 37 years.

In 1993, well before chassis 3535 resurfaced, noted Corvette restorer Kevin Mackay of Valley Stream, New York was able to obtain chassis numbers for all three Cunningham Corvettes that raced at the 1960 24 Hours of Le Mans via contacts in France. This information would eventually prove crucial in confirming the identities of all three of the Cunningham cars, including this storied Corvette.

REDISCOVERY OF 3535

In early 2011, a Tampa classified appeared online for a “pre-production, Zagato-bodied, Pontiac prototype,” with a low asking price that reflected its still-obscured history. The seller, Rick Carr, was clearing out the estate of his recently deceased father, the Hon. Richard W. Carr, Sr., and uncovered the neglected chassis in a corner of his father’s warehouse. The car’s status as one of the Cunningham Le Mans entries was unknown to Carr until he began researching the chassis number. This research eventually led him to Cunningham historian Larry Berman, who was able to confirm that he was in possession of a very special car, the #1 Cunningham Le Mans entry.

Presented today in “as-found” condition, this unique chassis still presents conclusive evidence of its racing history, despite Boswell’s best efforts to completely transform its appearance. Inside the wheel wells, bespoke intake ducting is aimed at the car’s original race-spec drum brakes and continues into the cabin footwell. An additional wiring harness still hangs from where it would have powered the driver’s side roundel light at Le Mans.

The oversized fuel tank remains behind the cabin, and the underbody shows evidence of mounting points for additional components such as oil coolers—as well as safety straps and cutouts for the side-exit race exhaust that once serenaded the French crowd of nearly 250,000. Ahead of the windshield sits a mounting hole for the central windshield wiper used at Le Mans, a key feature that helped enable the initial identification of this chassis, while a patch on the rear decklid clearly shows where the quick-fill fuel assembly previously emerged.

Inside the engine bay now sits a 350 cubic-inch Chevrolet V-8 from the 1970 model year. A mounting plate for the Duntov-specified remote starter is still tacked to the firewall, however. Telling traces of the car’s original Le Mans livery have been preserved under the subsequent layers of paint, while the center console, still displaying its original blue finish, is partially retained.

With Cunningham’s #2 and #3 Corvettes having been restored to their 1960 Le Mans glory, this car, chassis 3535, is fully deserving of a similar treatment. It is surely among the most important Corvettes ever offered to the public; a testament to Briggs Cunningham’s dogged efforts to prove America’s mettle on the global motorsports stage, this chassis played an undeniable role in the push that finally brought him victory at Le Mans in 1960—a victory that helped cement the Corvette’s reputation of “America’s Sports Car.”

| Amelia Island, Florida

| Amelia Island, Florida