1933 Pierce-Arrow Model 1239 Silver Arrow

{{lr.item.text}}

$3,740,000 USD | Sold

{{bidding.lot.reserveStatusFormatted}}

- The car that inaugurated the streamlined automotive age

- Recognized as the 1933 Chicago World’s Fair show car

- Formerly owned by D. Cameron Peck and Henry Austin Clark Jr.

- One of three known survivors of five originally built

- An impossibly rare and desirable CCCA Full Classic

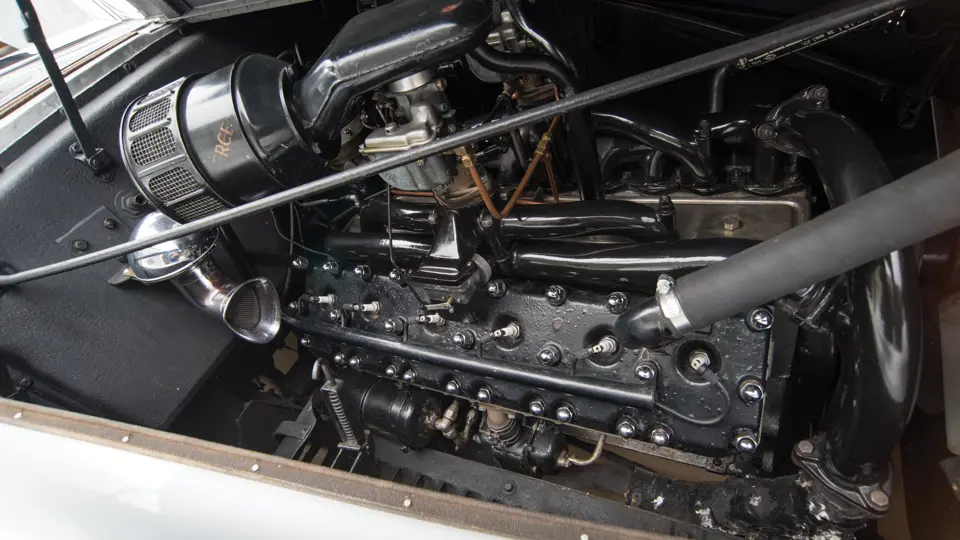

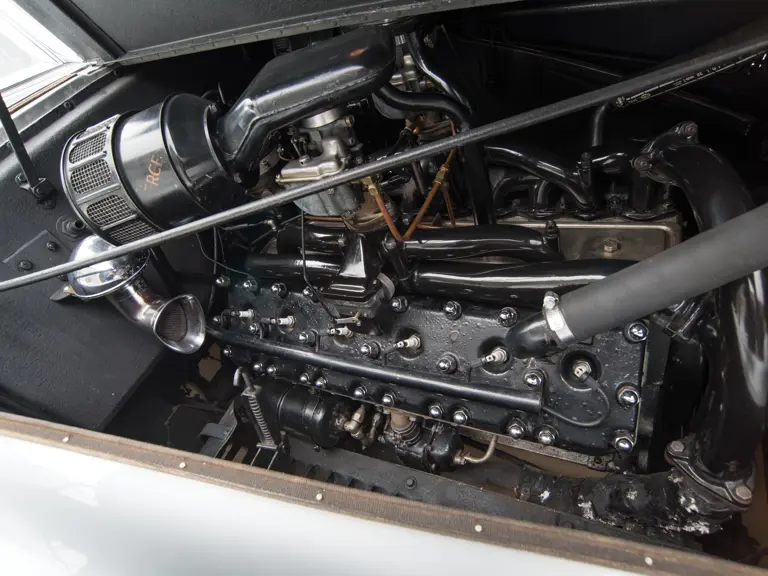

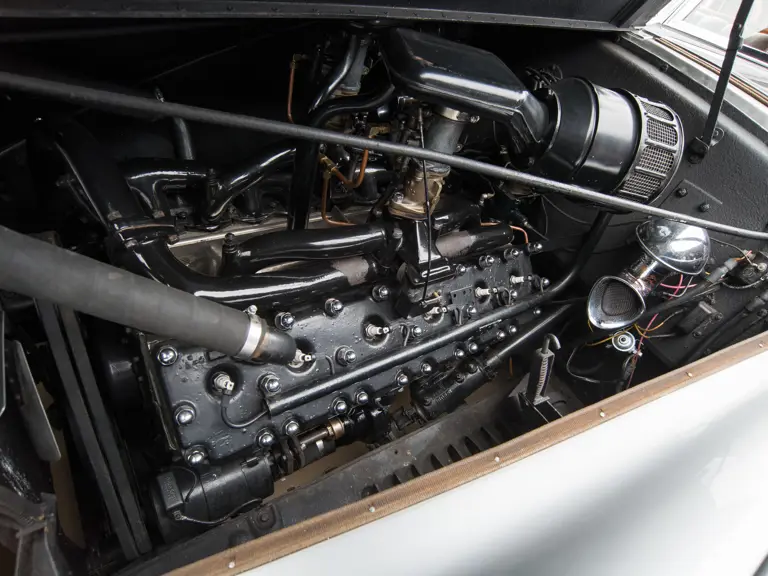

160 bhp, 429 cu. in. side-vale L-head V-12 engine, three-speed manual transmission, solid front axle with semi-elliptical leaf-spring suspension and ball bearing shackles, and four-wheel Stewart-Warner power-assisted drum brakes. Wheelbase: 139 in.

A CENTURY OF PROGRESS

On May 27, 1933, 427 sparkling acres of the best technology that man could produce opened to the world in Burnham Park on the Lake Michigan shoreline of Chicago. Dubbed “A Century of Progress,” the 1933 World’s Fair brought the world’s achievements to the Windy City. The Graf Zeppelin drifted in from Germany, the first Major League Baseball All-Star Game played at Comiskey Park, and the streamlined Zephyr train made a record-breaking dash into town for display.

Most dazzling for car enthusiasts was undoubtedly the Travel and Transport Building, which showcased the best and, frequently, most expensive automobiles that America had to offer. There was the one-off Duesenberg Model SJ Torpedo Sedan, nicknamed “Twenty Grand” for its cost in 1933 dollars, and Packard’s advanced V-12-powered Sport Sedan, known as the “Car of the Dome” for its central position in the building. Cadillac presented a sleek fastback Aero-Dynamic Coupe with no fewer than 16 cylinders.

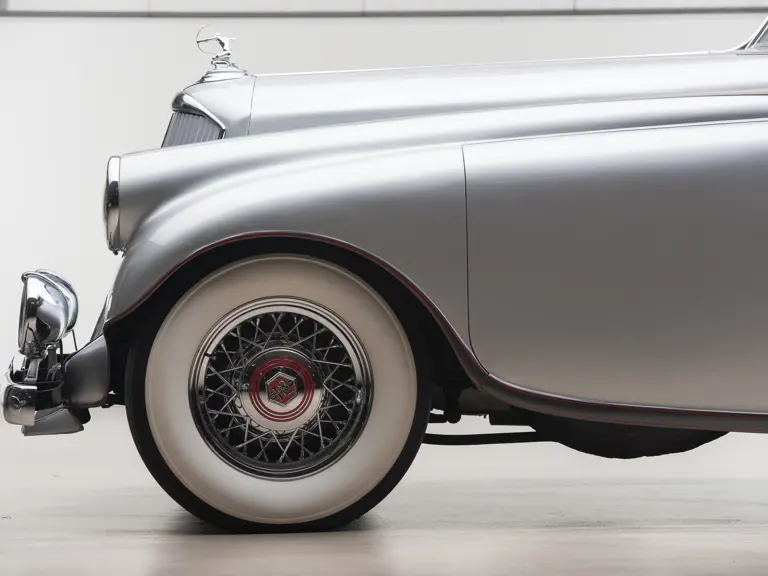

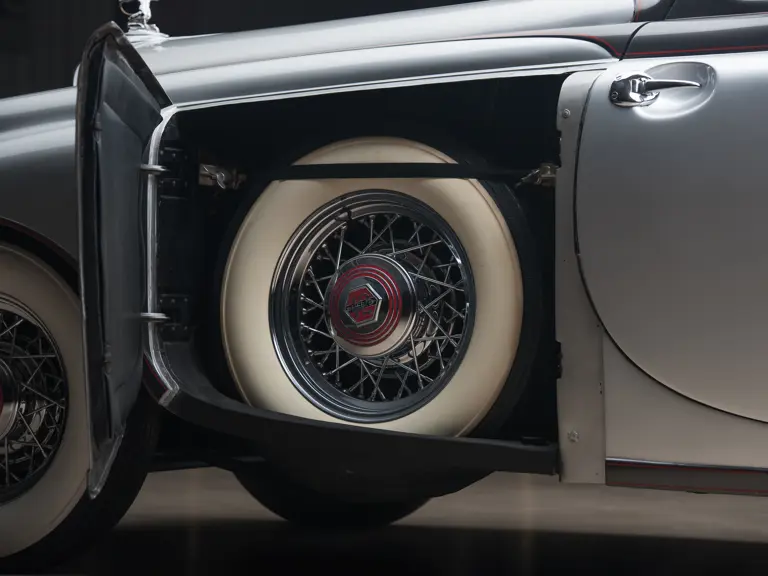

Even among this rarefied company, Pierce-Arrow’s Silver Arrow stood out. Its creation was a meeting of the minds of youthful stylist Phillip O. Wright and new Pierce-Arrow President Roy Faulkner. Based upon a 139-inch-wheelbase, 12-cylinder chassis, it had an automatic clutch and power-assisted brakes, among other advances. But these advancements all paled in comparison to the gleaming silver coachwork, a streamlined design with a roof that covered, in one smooth plane, all of the way to the rear of the car; flush-fitting doors with door handles inset out of the airstream; and a “step-down” interior that predicted Cord by three years and Hudson by 15.

According to Paul J. Auman, the superintendent of Studebaker’s experimental body department, as quoted in the December 1999 issue of Collectible Automobile, the first Silver Arrow was sent to New York in time for the Automobile Show held there earlier in the year. The second, fourth, and fifth cars were sent to the Pierce-Arrow factory in Buffalo, New York, for various promotional uses. Meanwhile, this example, car number 3, was the one sent to Chicago for viewing at the “A Century of Progress” exhibition.

SILVER ARROW NUMBER 3

The car offered here is strongly believed to have been the number 3 Silver Arrow that was shown at A Century of Progress, and it has been recognized as such from very early on in its life. The World's Fair car is said to have been sold, following the festivities, to an artist living in nearby Lake Forest, Illinois. Lake Forest is roughly two miles from Lake Bluff, the town where, in the late 1930s, the car offered here was owned by Charles Overall, who was an illustrator known for his depictions of Abraham Lincoln and Charles Lindbergh.

Records held by the National Automotive History Collection of the Detroit Public Library confirm that the car offered here, serial number 2575029, is that which belonged to Mr. Overall and that he eventually sold it for $250 to D. Cameron Peck, heir to the Bowman Dairy fortune in Chicago and a prominent early car collector. The car’s early Chicago provenance lends further credence to its having been the World’s Fair car, as neither of the other two surviving Silver Arrows are known to have spent time in the Windy City. Peck’s handwritten notes on the inventory form for this car also indicate it as the “A Century of Progress” car.

In the late 1940s, Peck began to move out of the hobby, and in 1949, he sold the Silver Arrow, still in unrestored condition, to Henry Austin Clark Jr., as is documented by paperwork on file.

Best remembered as the personable and colorful proprietor of the Long Island Automotive Museum near Southampton, Clark was a Peck contemporary among early enthusiasts. Clark’s interest focused on Brass Era automobiles, which he gathered extensively and, in the process, saved from certain destruction at the hands of scrappers. He was interested in Classics as well and was a longtime CCCA member. His interest in the Silver Arrow was likely provoked by its rarity and unique styling, as well as by its story. Always one to enjoy a good tale, “Austie” liked to muse that the car had probably been part of the Capone mob fleet.

The Silver Arrow was brought by train to New York State and was restored completely by the renowned Gustav Reuter’s Reuter Coach Works in the Bronx. Photographs on file from the Reuter Coach Works Archive dated June 18, 1950, show how well preserved the car’s bodywork was after two decades and that it remained solid, intact, and complete, making it an easy basis for restoration. Documents from Austin Clark’s files, copies of which are included in the file, note that the Pierce was refinished at Reuter’s suggestion in French Grey lacquer.

Following completion of the restoration, the Silver Arrow remained a favorite part of the Clark collection on Long Island for over a decade. It was, during that time, a favorite of enthusiasts and magazine editors alike, appearing in the pages of Mechanix Illustrated and in a beautiful color drawing in their competitor Popular Mechanics’ book How to Restore Antique & Classic Cars in 1954. In 1962, Automobile Quarterly, which would become one of the most famous automotive periodicals in the country, published its inaugural issue, Volume 1, Number 1, which included Henry Austin Clark Jr.’s selection of 10 great automobiles illustrated with paintings by the legendary Leslie Saalburg. Naturally, Austie’s own Silver Arrow was included, depicted by Saalburg in the shadow of the Brooklyn Bridge.

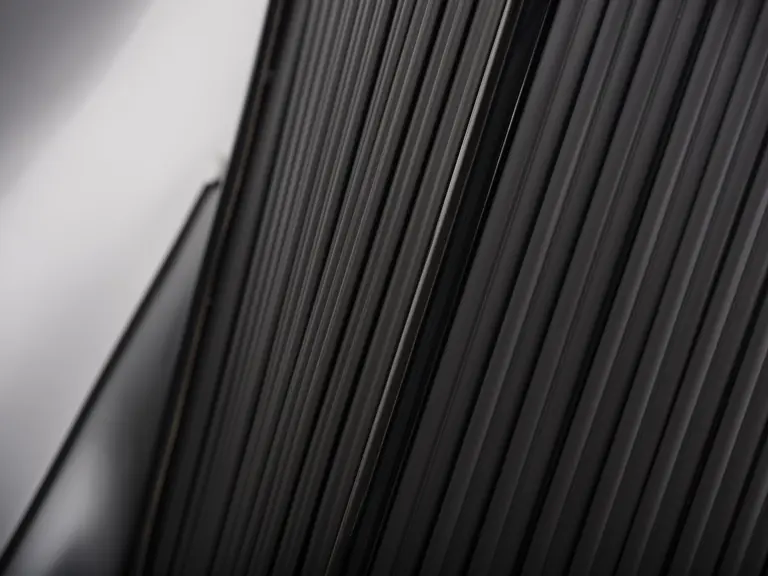

In 1963, the car was sold at the first of three landmark auctions of Clark’s automobile collection. It eventually made its way into the collection of its present owner, where it has remained for over two decades. In the early 1990s, it was refinished, with the body painted a lightly metallic pewter with a dark charcoal molding, striped in red. The interior is finished in correct striped broadcloth, surrounded by beautiful tiger and birdseye maple. The Silver Arrow has been maintained over the years and presents nicely, retaining so much of the original character that has been stripped away from many cars during well-intentioned restorations.

Among the numerous legendary show cars that made a massive impression at A Century of Progress, the Packard “Car of the Dome” and Duesenberg “Twenty Grand” remain in long-term private collections from which they will not soon emerge, and Cadillac’s Aero-Dynamic Coupe no longer survives. That leaves the World’s Fair Silver Arrow—now offered publically for the first time in at least three decades—as the only present opportunity to acquire one of these dramatic visions of the future.

| New York, New York

| New York, New York