1964 Chevrolet CERV II

{{lr.item.text}}

$1,100,000 USD | Sold

{{bidding.lot.reserveStatusFormatted}}

- The brainchild of the “Father of the Corvette”

- Zora Arkus-Duntov’s legendary Corvette engineering test vehicle

- The first known operating example of torque-vectoring, all-wheel drive

- Ex-Briggs Cunningham Automotive Museum, Miles Collier, and John Moores

The 1950s were a Golden Age for American car companies, but this was not by chance; it was because of designers and brilliant engineers like Zora Arkus-Duntov. Indeed, few innovators can take credit for redirecting the entire focus of an industry. He is rightfully regarded as the “Father of the Corvette,” taking the staid powerplant of its inaugural year and infusing a much-needed injection of youthful aggression: a powerful small-block V-8 that took the Corvette from a delightful cruiser to an all-out sports car. Fuel injection was added to the model in 1957, and a rip-snorting Grand Sport program took hold in the early 1960s. From there on out, the Corvette had cemented its status as “America’s sports car,” as it was capable of going up against the finest competition from Europe, both on the track and from stoplight to stoplight on Woodward Avenue. Here was a man who not only understood the importance of performance, but he also intimately understood its market. The American driver wants fast, he wants loud, and he wants to win.

In order to win, General Motors needed to stay on the cutting edge, and rumors kept circulating that the next Corvette would be mid-engined, in keeping with the developments at Ferrari and Ford, with its GT40. The rumors were largely based on facts, as Chevrolet had been one step away from such a car with its radically different “Chevrolet Engineering Research Vehicle II” (CERV II).

The most extraordinary characteristic about CERV II was Duntov’s attempt at four-wheel drive.

He had been interested in a high-performance, four-wheel drive vehicle since 1935, when he witnessed the startling straight-line acceleration of the “integral drive” Bugatti T53 race car. He also witnessed the Bugatti’s difficulty with maneuvering, as well as the trouble drivers had in managing it. “The problem of force transmission to the ground is almost always present in the design and operation of a racing car,” Duntov wrote in a 1964 memo, “but in the mid-thirties, with 650 horsepower and under 2,000 pounds of running weight...this was a real problem. However, four-wheel drives visualized at that time did not promise to be satisfactory, and one case of execution did not meet with success.” In the late 1950s, with Chevrolet General Manager Bunkie Knudsen and the engineering might of General Motors behind him, Duntov was able to tackle the problem.

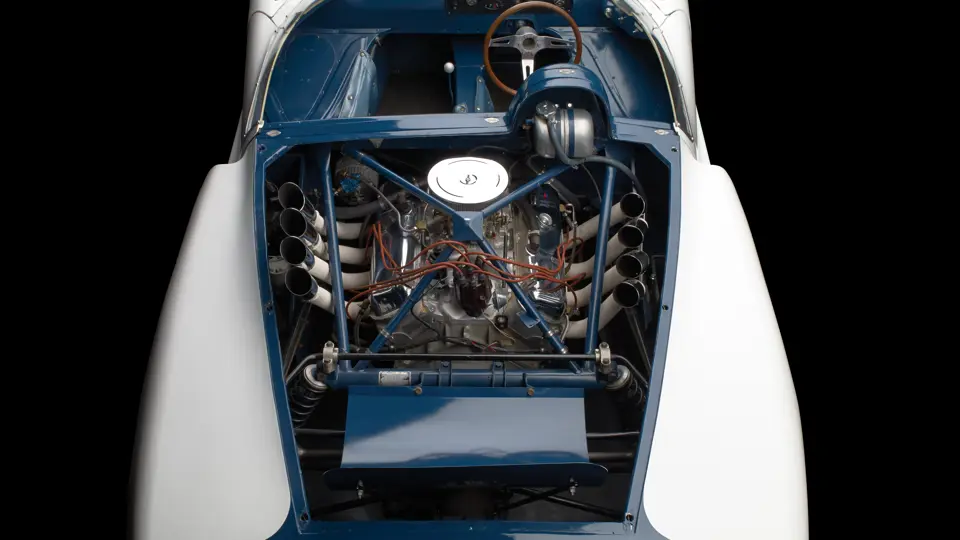

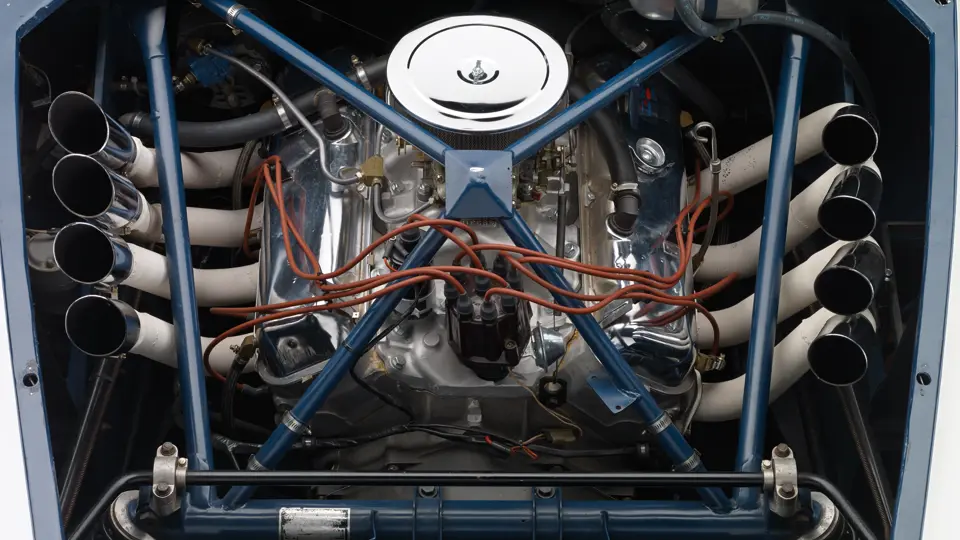

The first Duntov Chevrolet CERV was completed in 1960, and it was aimed at open-wheel racing. While it featured advanced construction, it was a relatively conventional design that resembled contemporary IndyCars. Its most notable feature was an all-aluminum pushrod, 377-cubic inch small block that evolved from the 327, which went on to see use in racing Corvette Grand Sports in 1963. It was light and capable of 500 brake horsepower, making it the ideal powerplant to design into the next car.

Duntov began work on the successor in late 1961, intending “to incorporate all the features necessary to make it a successful contender, not only in sprints but in such long distance events as Le Mans and Sebring.” His plan was for a run of six cars, originally designated the G.S. 2/3, “to permit selective usage as two-wheel drive (G.S. 2) [or] four-wheel drive (G.S. 3).” Using the Grand Sport label, as well as frequent references to the Corvette, suggests a familial relationship was on their minds.

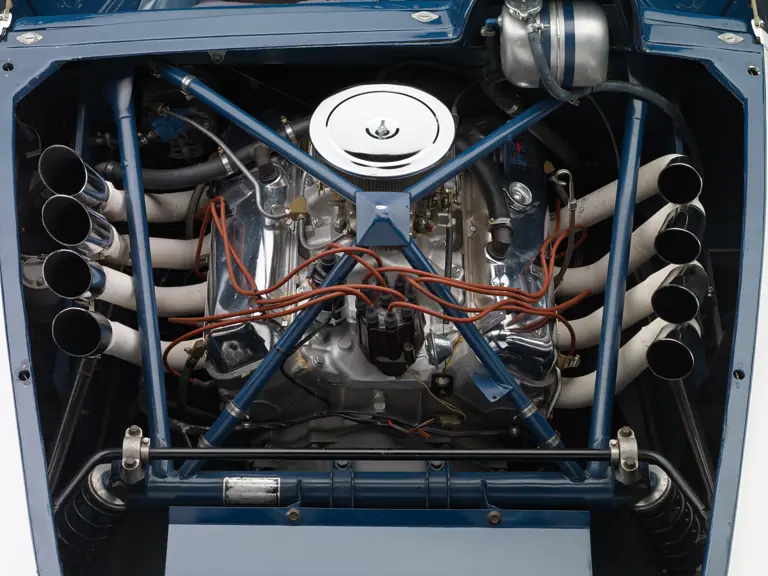

Four-wheel drive and the 377 were the starting point for the G.S. 2/3, with members of the same team from CERV I on hand, including engineers and builders Walt Zetye, Ernie Lumus, and Bob Kethmann and stylists Larry Shinoda and Tony Lapine, who were responsible for the stressed fiberglass body. With them, Duntov was able to combine 25 years of thinking about advanced powertrains made with lightweight, Space Age, high strength materials in order to make his car possible. The target weight was a scant 1,400 pounds, and in the initial configuration, it was reportedly near to that, thanks to titanium hubs, connecting rods, valves, and an exhaust manifold.

The four-wheel drive system is equally unconventional. An 11-inch Powerglide torque converter and clutchless two-speed manual gearbox hang from the rear of the car. A driveshaft from where a harmonic balancer would normally be extends to a second 10-inch Powerglide torque converter at the front of the car, with a second semi-automatic transmission. Over the course of hundreds of subsequent skidpad laps through the sixties, Chevrolet tried numerous torque split ratios and gears, with Duntov aiming for 35% of the power delivered to the front end at low speed and 40% at high speed. Much of this technology is related to the automatic transmission that soon appeared in Jim Hall’s Chaparrals via the Chevrolet GSIIa and GSIIb prototypes, with which Hall was more closely involved. Despite the similar names, these were completely different cars that had been built by Chevrolet R&D Chief Frank Winchell.

Ferrari’s 248 SP race car was originally benchmarked as the G.S. 2/3’s target. The Ferrari was ultimately not very successful, but as the Chevrolet came together during 1963 and 1964, it roughly coincided with Ford’s GT40, and had it gone racing, it would have been a direct competitor. Interestingly, the G.S. 2/3 body “did not represent the best open car configuration, but rather the lower part of an aerodynamic coupe,” which the six production cars were to be. Even so, with high-speed gearing and between 500 and 550 horsepower from the 377, Chevrolet saw 212 mph on the track. Geared for a sprint, it was capable of 2.8 seconds to 60 mph.

In the spring of 1964, around the time the car was completed, General Motors informed Knudsen and Duntov that any ideas they had for racing were off the table. Repurposing it as CERV II, Duntov staunchly defended the single prototype, writing, “We feel that in case we are not permitted to go racing, we should obtain permission to demonstrate it...It will show that although GM is not in racing, its engineering is more imaginative and more advanced than anyone else [sic].”

Demonstrations were limited and perhaps not necessary, as racing Corvettes, including the Grand Sport (itself something of a testbed for the 377 engine for CERV II) and Z06, appeared at the same time. CERV II became a test vehicle for future exotic Corvette ideas, and it saw major outings, at least in 1964, 1968, 1969, and 1970. These included tire testing both the original Firestones and new Goodyears, aerodynamic research, and top speed testing at Milford Proving Grounds. The bulk of test time seems to have come from Corvette test driver Bob Clift, who spent hundreds of laps investigating roadholding on a skidpad, where CERV II achieved up to 1.19 Gs in steady state cornering.

Around 1969, Chevrolet began testing CERV II with a new all-aluminum 427-cubic inch ZL1 V-8, which Duntov later said he “retrieved...in the nick of time from the crusher.” He believed this powerplant was capable of 700 horsepower, and he said that he felt that the car was capable of breaking Mark Donohue’s 221.160 mph closed course speed record. In its final (current) configuration, power is conservatively estimated at 550 horsepower, and it weighs 1,848 pounds.

Chevrolet’s last test results are from 1970, after which it was placed into storage. As late as December 1974, when it was sent to the Design Staff Warehouse in Warren, Michigan, it was accompanied by not only a ZL1, but also a spare fuel-injected 377 with dual ignition and a third unspecified SOHC fuel-injected engine, as well as probably another 377. Multiple boxes of spares were also with the car, including 18 unique Halibrand CERV II knockoff wheels. These materials have since disappeared. Shortly thereafter, GM officially retired CERV II and donated it to the Briggs Cunningham Automotive Museum in Costa Mesa, California, where it was displayed for the next 10 years and was periodically shown and even exercised.

When the museum closed in 1986, noted collector and enthusiast Miles Collier acquired the collection, before it was eventually sold to noted philanthropist and car collector John Moores. Mr. Moores eventually chose to donate the car to the Scripps Research Institute, from which it was sold in 2001 to its present caretaker, benefitting SRI’s important medical programs.

Given that the entire drivetrain and running gear was essentially hand fabricated by Chevrolet, and that it is unique to CERV II, the fact that the car is in one piece today is an indication that it must have the same parts it did in 1970. There is no evidence of any significant damage, and its longtime caretaker attests that the blue and white paint appears to have been applied in 1964. A few minor inconsistencies, such as later spark plug wires, probably from the Briggs Cunningham era, have been rectified during the consignor’s 12 years of custody, and it is fully, and almost entirely, in correct period configuration.

The same irreplaceable mechanical components that speak to CERV II’s originality have limited its use in recent years. Nevertheless, it is operational and will still demonstrate performance that will give any modern supercar nightmares.

Chevrolet Engineering Research Vehicle II is among the most important Corvette development vehicles in private hands today. Since leaving General Motors, it has only been owned by four collectors, the Briggs Cunningham Museum, Miles Collier Jr., John Moores, and, of course, the current owner, a well-respected collector in his own right. Its provenance is matched only by its extraordinary performance and earth-shattering horsepower.

| New York, New York

| New York, New York