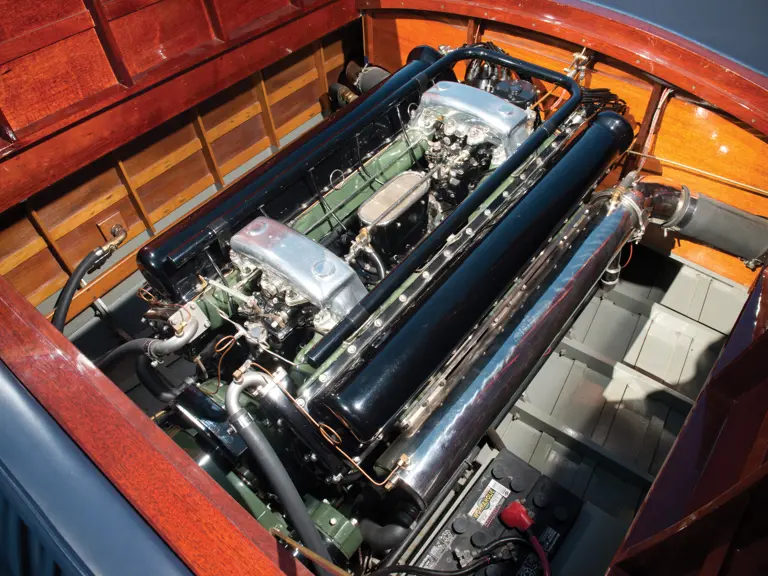

520 bhp, 1,497.5 cu. in. DOHC Packard V-12 engine, and V-drive. Length: 26 ft.

“Unlimited” has always been a stirring name in any motorsport, and it certainly applied to the runabouts that competed in late 1930s K-class racing. David Gerli’s Ventnor-built Lady Gen VI, commonly known as just Gen VI, certainly lived up to the name, with a marinized Packard V-12 aero engine of the same family that spawned World War II’s legendary Merlin.

On September 23, 1939, Mussolini was making noise about entering the war and the French were still holding Germany, but American manufacturing had not yet been converted to war production, and our young men were still able to have fun. So, on the 23rd of September, instead of fighting, David Gerli was in Gen IV at the President’s Cup in Washington, D.C., setting a new one-mile class record of 61.7 mph.

Builders Ventor Boat Works, in New Jersey, were at the cutting edge of racing boat design. They were known for an unusual combination of beauty and innovation and were responsible for some of the fastest boats of the time, including Sir Malcolm Campbell’s famous Bluebird K4, although that has been disputed. Not in question is their crucial role in developing the three-point hydroplane, along with many other important marine inventions.

The late 1930s were Ventnor’s heyday, when the small shop was swamped with orders—you really had to be someone to get one of their boats. E. Mortimer Auerbach, racer of the immortal Emancipator series of boats and the era’s most famous speedboat racer, certainly qualified. Ventnor founder Arno Apel designed the hull, and they sourced an engine from Melvin Crooks’ Gold Cup winning Betty V. The Ackersly-Packard V-12 was nominally rated at 500 horsepower at 2,000 rpm, with period reports rating it as high as 800. Today, 520 horsepower at 2,200 rpm is the currently accepted figure.

Mortimer Auerbach died before he was able to compete, and racer David Gerli purchased her to become the next in his line of rough-water boats, after the very successful Lady Gen V, which had been raced by Melvin Crooks. In the true spirit of the gentleman racer, Crooks both piloted Gen VI and, at times, competed against it.

In competition from the time of its launch, Gen VI’s peak came between 1939 and 1941, notching up both individual speed records (peaking at 68.70 mph) and head-to-head competition. Ironically, what may be Gerli and Gen VI’s most significant moment was overshadowed by another boat.

The big story of the 1940 Gold Cup race off Long Island was the huge upset victory of Hotsy Totsy III. Almost lost in the uproar was the realization that in a separate five-mile heat for inboard runabouts in the Unlimited class, David Gerli’s big, heavy Gen VI won with a faster time than any recorded by Hotsy Totsy III in the main event.

Gerli continued racing Gen VI right up to the war. Class wins included the 1940 New Jersey Governor’s Trophy, the 1940 APBA Gold Cup, and the 1940 President's Cup in Washington, D.C., where he set his class world record, while 2nd place finishes included the 1940 American Speedboat Championship and the 1941 Gold Cup.

She was back on the water immediately after the war and purchased by Baltimore’s Harry Link in 1946. The Rudder reported that Gerli had topped 71 mph by that point, thanks to continual refinement of the boat.

Eventually, she ended up in storage at a marina on Lake Champlain, where she was long a target for acquisition by collectors. Ultimately, a well-known Massachusetts dealer was able to acquire her and begin restoration, but the partially-restored Gen VI was eventually sold to Tom Mittler.

It’s little surprise that Gen VI made its way into Tom Mittler’s hands. It was just one of a large number of important, restored racing boats kept at the Mittler Boat Barn in Three Rivers, Michigan, and a wonderful complement to his collection of important sports cars. He contracted Michigan specialists Morin Boats to complete a restoration of the hull.

Because of the rise of hydroplane racers, the open water, Unlimited K-class boats were less well known. The hydroplanes required flat water, which meant they ran on lakes, rivers, and close to shore. Gen VI was built to go offshore, a clear precursor to the cigarette of the 1960s. Unlike a hydroplane, however, there’s no reason an adventurous person today couldn’t take Gen VI out for a casual day cruise, puttering along with the mighty Packard at idle, all the time aware of the fury ready to be unleashed at a whim. A lover of transportation will seldom have another opportunity to find such a perfect fusion of automobile, aviation, and nautical together in one historic vehicle.

| Monterey, California

| Monterey, California