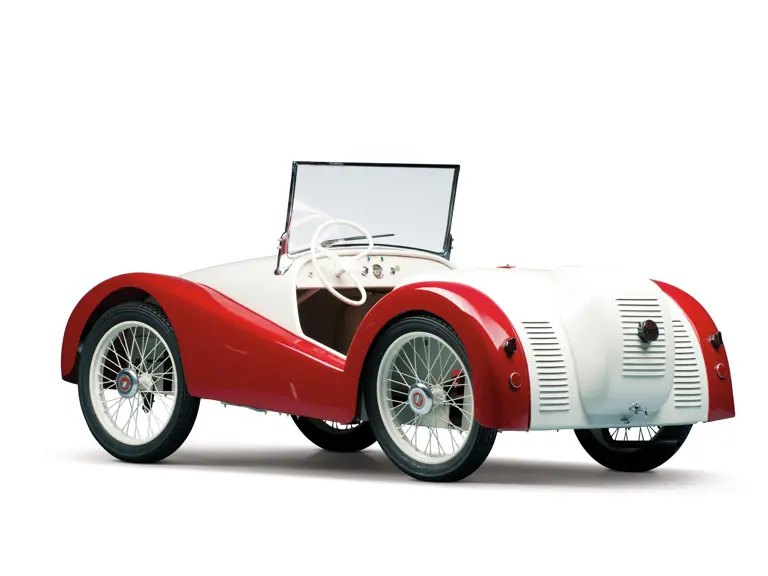

One of two examples known to exist worldwide.

SPECIFICATIONS

Manufacturer: Hermann Holbein Fahrzeugbau

Origin: Ulm, Germany

Production: 11

Motor: Triumph (DE) 1-cyl., 2-stroke

Displacement: 248 cc

Power: 6.5 hp

Length: 9 ft. 2 in.

Identification No. N/A

In 1945, Hermann Holbein, a former development engineer for BMW, recovered his beloved BMW 327 sports car from the haystack where it had been interned and reluctantly gave it up to an American GI in trade for an Opel-Blitz army truck. He made a lucrative business out of picking up scrap metal and transporting various materials into a devastated country bent on cleaning up. He picked up a scrap BMW 328, rebuilt it, and Holbein made a name for himself as a successful racing driver for the next three years.

Racing did not pay the bills, however, and he resolved to fill the post-war need for a small car, which he would design and sell the production rights to. A chance meeting with an old acquaintance, engineer Albert Maier of the gear-making firm ZF, brought together their individual interest in building a small car. In fact, Maier had already built a very basic open roadster with the backing of the ZF Company. In January 1949, Holbein came to a licensing agreement with ZF to build the car, raising the money by selling his three racing cars and two trucks. It would be called the Champion, with a nod to Holbein’s racing successes.

Holbein and Maier saw the need for the development of the little car and worked out the design for a custom transaxle driving the rear wheels and incorporating inboard brakes. Meanwhile, the prototype used an Irus lawnmower gearbox. The new, stylish, aluminum body was found to be too expensive to make, so Holbein modeled a simpler body in clay, and his racing mechanic built it using a bent flat sheet and motorcycle fenders. Aluminum discs hid the tall wire wheels’ humble motorcycle origins. There was a single “Cyclops” headlight, and the 198-cubic centimeter Triumph motor, along with its cylindrical fuel tank, sat nakedly out in the open on the tail. It was called Champion CH-1, and it made its debut at the Reutlingen show in April 1949. Orders flooded in, but the vehicle was not yet ready.

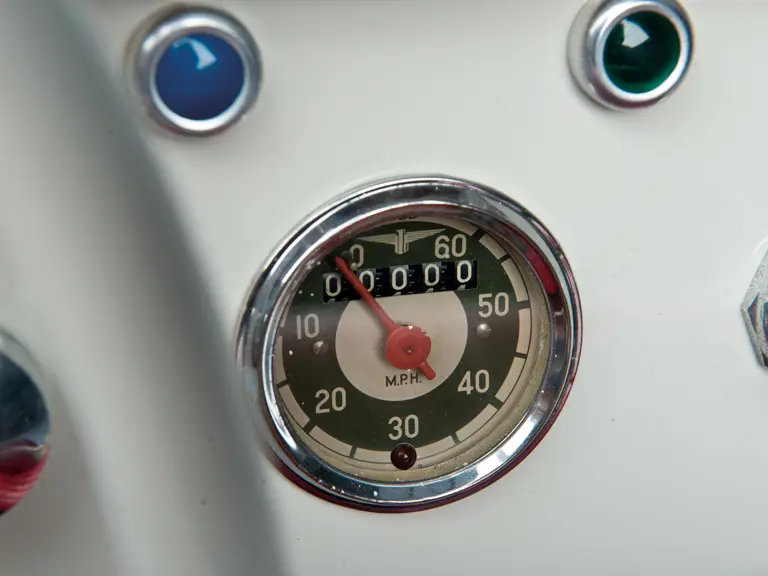

Development continued, and companies that could supply parts had to be found. The Hörz Company in Ulm made large clocks for clock towers, and they agreed to make the transaxles. The new ZF transaxle was incorporated into the two upgraded CH-2 prototypes, along with a new Triumph 248-cubic centimeter motor used as a stationary engine in farm applications, which was now under a louvered cover. Bosch in Stuttgart supplied the generators, Continental in Hannover supplied the tires, Schleicher in Munich supplied the hubs, and Hella in Lippstadt supplied the lamps. Former aircraft builder Böbel had a press, and they agreed to do the body shells.

Production of the CH-2 got underway, and the press was enthusiastic about the new, small roadster. The first cars made it clear that the transaxle was not up to the job. The Hörz people refused responsibility, but ZF stepped in to help. In addition, teething problems with breaking in the front and rear suspension elements caused Holbein to take the drastic action of recalling all cars sold to date and refurbishing and upgrading the chassis to the latest specifications. The public’s faith in the new car was not shaken.

The CH-2 became the CH-250 in March 1950, with a new twin-piston motor, a split windshield, bumpers, and smaller wheels. This model would lead to the charming Champion 400 coupe and eventually to the Maico 500 sedan. Perhaps two of these CH-2 cars exist worldwide. The bare metal bodywork of this exceptionally rare car was completely remade by a master metalworker, and it was restored by the museum’s in-house staff; it runs and drives just as well as it looks.

| Madison, Georgia

| Madison, Georgia