Perhaps a few in the stands at Indianapolis in 1911 saw Harry C. Stutz’s creation coming, but they were in the minority; they were engineers and fellow veterans of the early automobile industry, and they knew Stutz’s genius. The car that he built under his own name averaged 62.375 mph for 500 miles in that first running of the 500, running with only minimal mechanical adjustment and 13 pit stops, 11 of which were for tires. Though it did not win the race, its durable performance was considered outstanding for a first independent-production effort. Stutz took advantage of the attention, promoting his automobile as “the Car That Made Good in a Day.”

The production version of that car was the Model A Bearcat of 1912. It was powered by a Wisconsin engine, and Harry Stutz’s mechanical brilliance increased its performance to an estimated 60 horsepower. This was fed to the rear wheels through a transaxle—a technological advancement that was some five decades ahead of its time. When installed on a 118-inch-wheelbase chassis with the Bearcat’s minimal bodywork, which comprised just seats and tanks, the Wisconsin T-head four propelled the extremely lightweight performance-designed car to superb speeds.

The sporty Bearcat was promoted by Stutz as the carbon copy of their racing model. “We are now building duplicates of this ‘car that made good in a day’ with absolutely the same material, workmanship, and design,” boasted the 1912 factory catalogue. True indeed, as men of the era, with money to burn and gasoline in their blood, took to the dirt and board tracks in Bearcats, setting up a heated rivalry with competitors—most famously the Mercer Raceabout of New Jersey.

This 1913 Stutz was discovered on a ranch in the 1970s by a pair of aerial surveyors doing work in Montana. At time of its discovery only a partial frame, engine, and a gas tank remained. A deal was struck, and the car was saved from the ranch. Despite years of parts collecting and sourcing, by the early 2000s, the car was still in an unrestored state—somewhat more “complete” but now languishing in a restoration shop. It was purchased that same year by a collector who finally began the much-deserved restoration on the Stutz. He and his son undertook much of work themselves over the course of the few years, including sourcing correct parts, some of which reportedly came from Harrah’s, the Los Angeles County Museum, and Paul Freehill. A story of the car’s restoration process was published in the October-December 2009 issue of the Stutz News club publication.

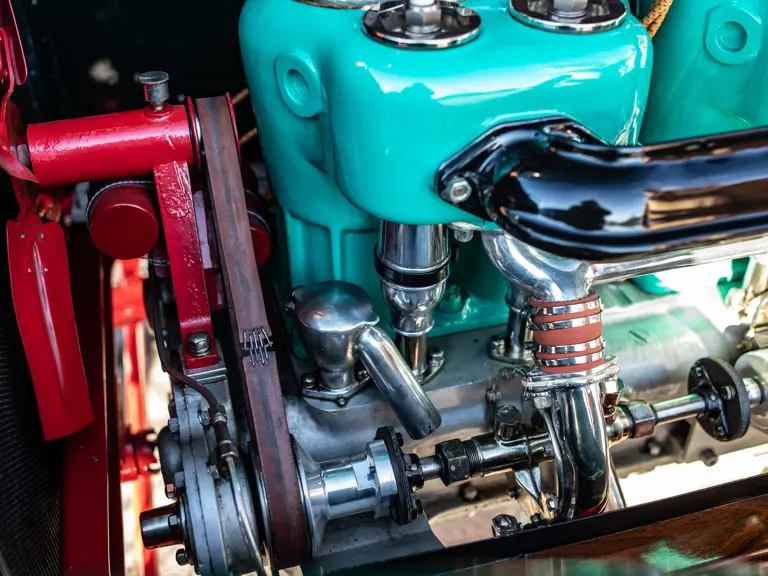

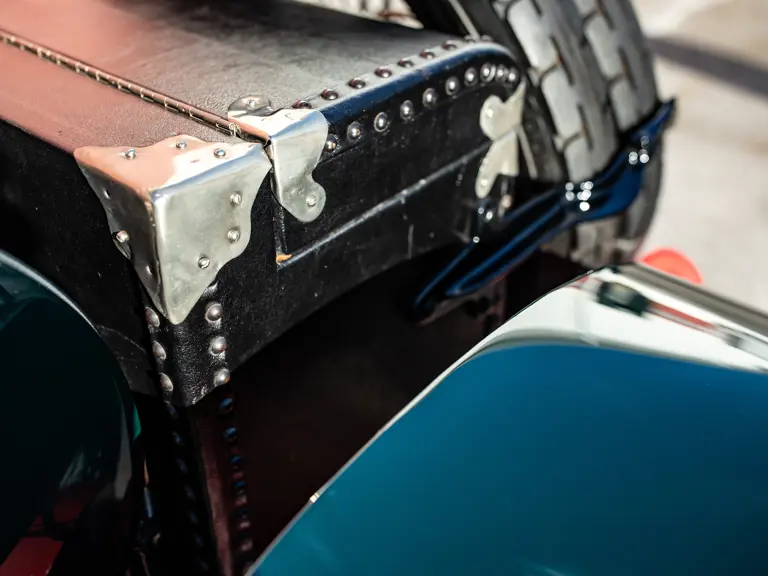

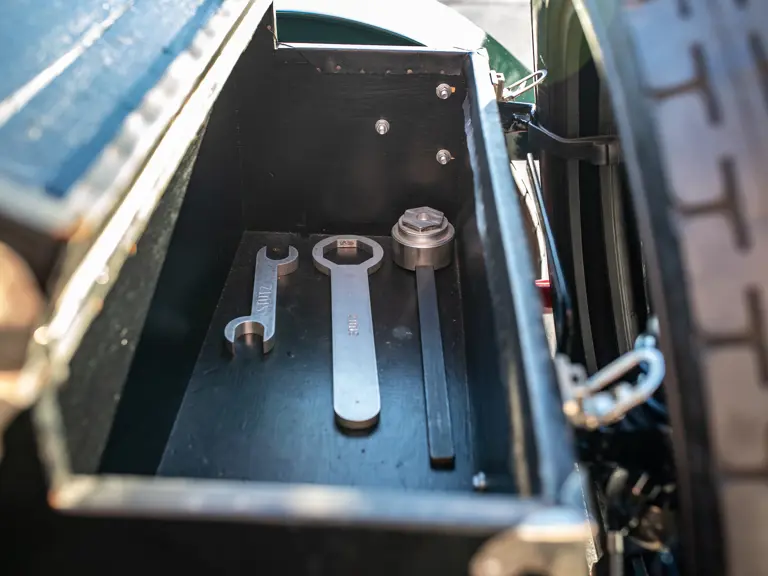

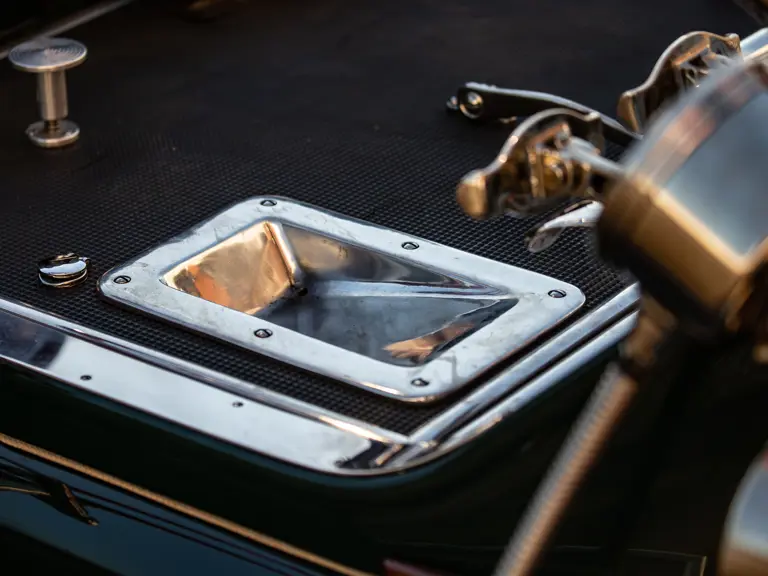

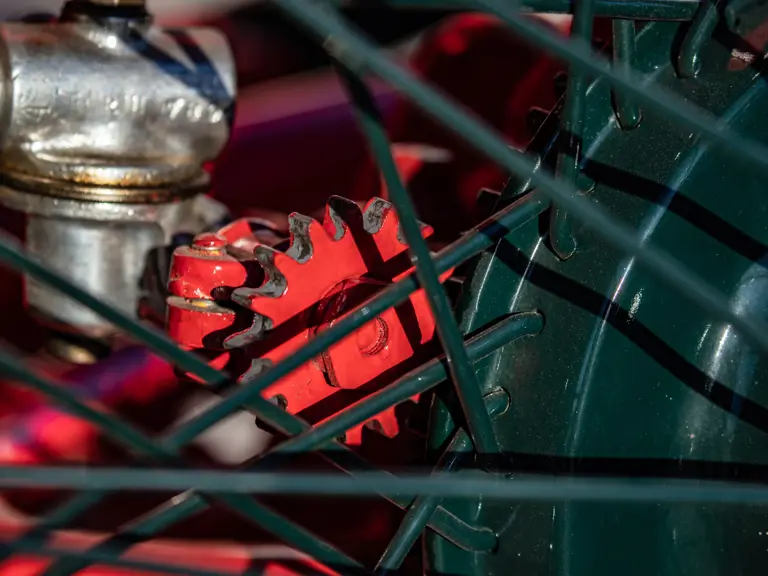

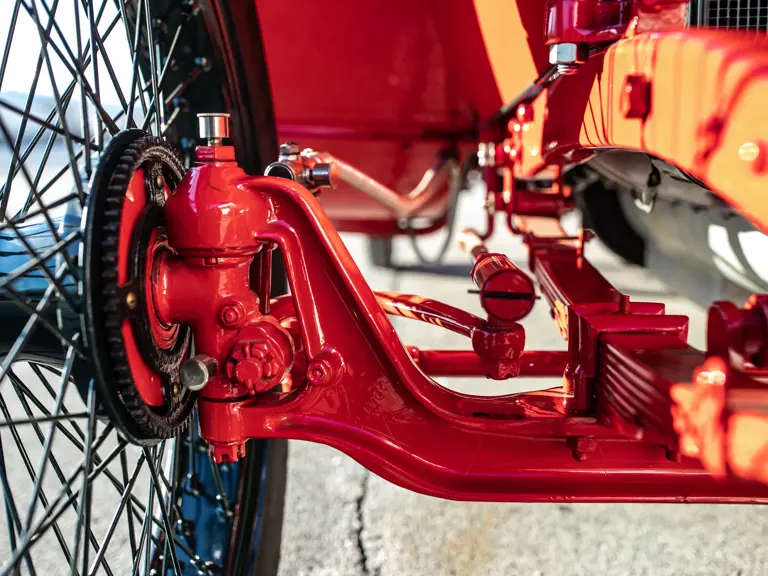

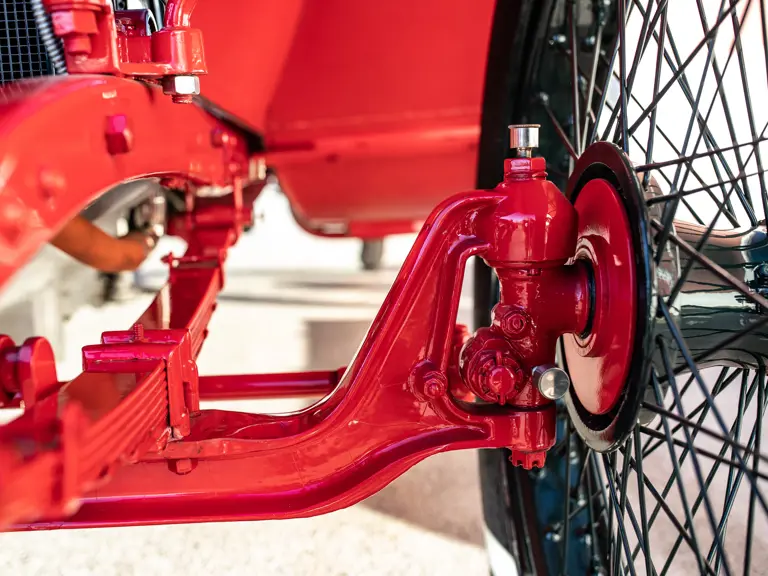

The car was acquired by current ownership in 2015, where it has remained in a well-respected private collection on the East coast. The restoration from years ago has been nicely maintained, and the Stutz presents in a beautiful shade of dark green with a contrasting red under the fenders. The chassis is also painted the same shade of red, giving the car a subtle two-tone color scheme. The Stutz rides on painted Frayer knock-off wire wheels with Goodrich Silvertown tires. Exterior features include adjustable front shock absorbers, Macbeth headlights with color-matched visors, dual cowl lights, a left- and right-side fill fuel tank, a storage trunk, and two full spares at the back.

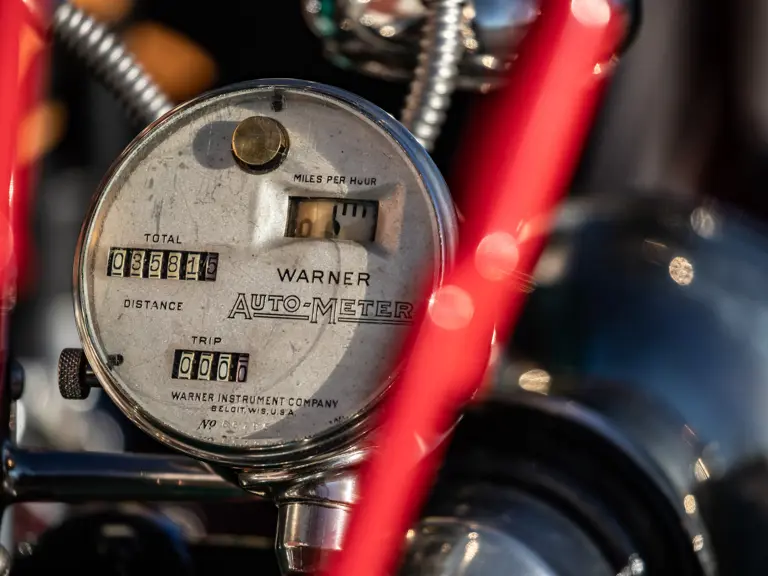

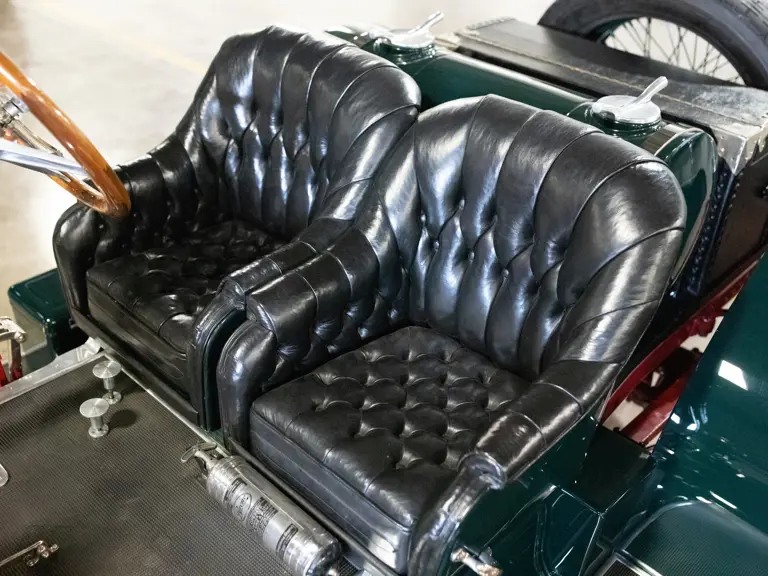

The interior is simple by today’s standards but luxurious for the period. It features a walnut wood dash, button-tufted seats, and a wood-rimmed steering wheel. Instrumentation includes a Warner Auto-Meter speedometer with total and trip counters, a Berdon System Esterline Co. amp gauge, a Phinney-Walker Co. eight-day clock, and a Tuto Type A horn. To the right of the driver’s seat is a nickel gated three-speed manual gear selector with a separate quadrant for the parking brake. Both the shifter and parking brake levers are painted red to match the chassis. Just below the front of the driver’s seat are two buttons: one to operate an added electric starter, and one to operate an exhaust cutout. On the passenger, side a Pyrene fire extinguisher is mounted just in front of the seat, and a foot rest makes travel slightly more comfortable.

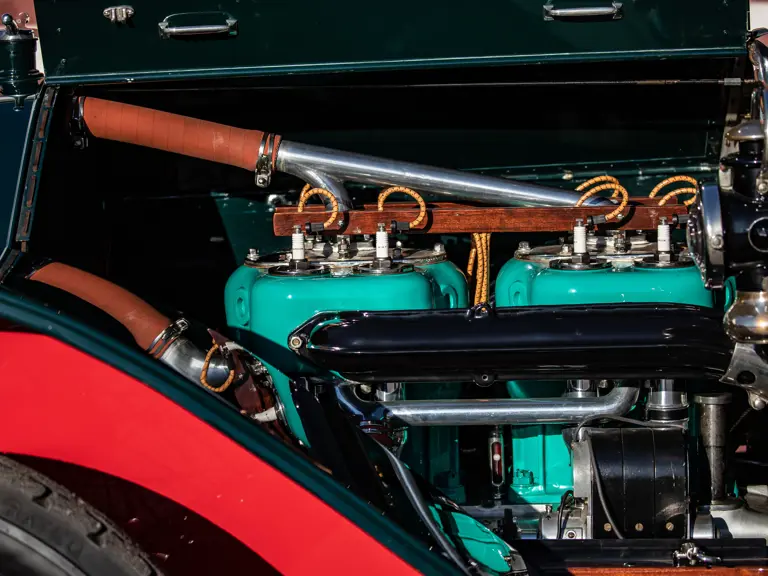

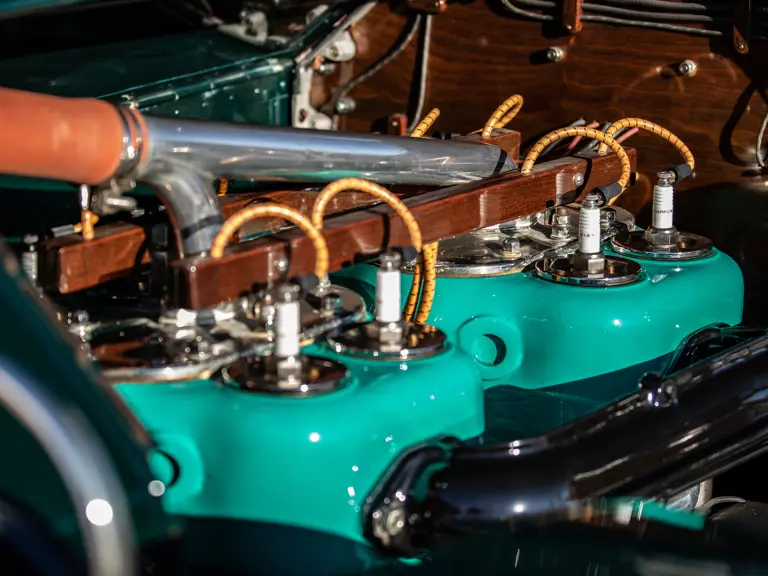

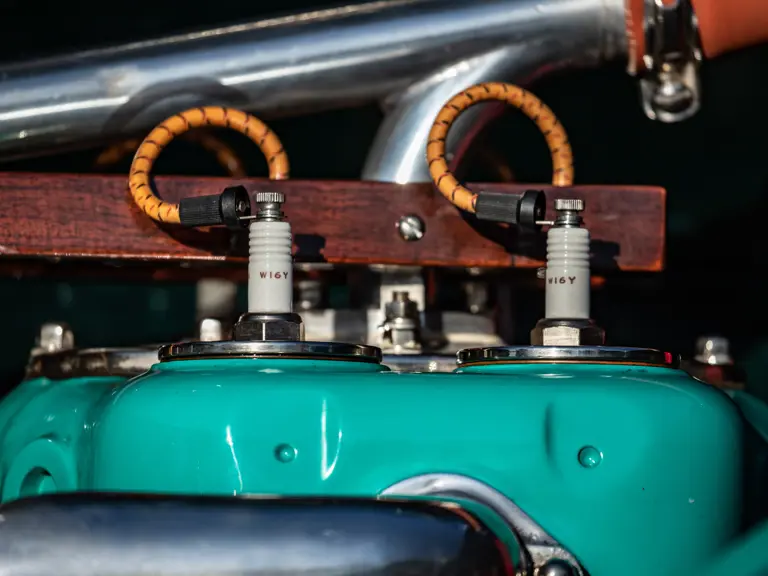

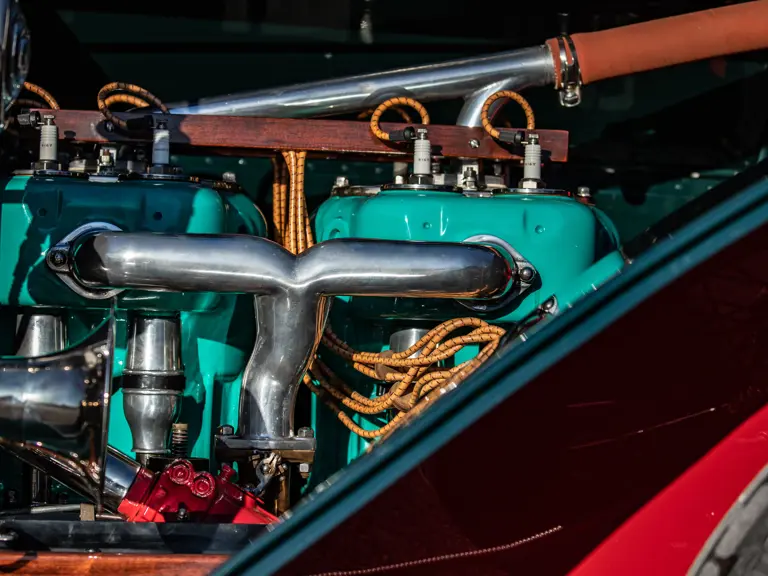

Under the hood is the powerful 390-cubic-inch Wisconsin T-head four-cylinder engine, which is fed via an updraft Stromberg carburetor. To ensure more enjoyable touring experiences, several upgrades have been made to the car. These are highlighted by the electrical system being upgraded to 12 volts, the addition of an electric starter, an ignition system upgraded from a magneto to a distributor setup with coils and points, and lastly, the fitment of a modern clutch.

Breathtaking to behold and thrilling to drive, the fortunate next owner will surely enjoy seat time behind the wheel of one of America’s early high-performance sports cars.

| Amelia Island, Florida

| Amelia Island, Florida