In a world saturated with excess, Gordon Murray continues his quest for minimalist perfection, says Mark Dixon.

What does the man who could have any car in the world drive every day? In Gordon Murray’s case, for much of this century it was a Smart Roadster, the tiny two-seater powered by a 698-cc engine. He used it as his daily driver for 16 years before replacing it with an Alpine A110, an equally modest choice for someone who oversaw five Formula One championship-winning cars before going on to create what many still regard as the finest road car of all time: the McLaren F1.

Twenty-seven years later, now an independent manufacturer, he launched the T.50 under his own Gordon Murray Automotive (GMA) label. What links the humble Smart and Alpine with the hypercar McLaren F1 and GMA T.50 is that, above all else, they are driver’s cars. They were designed not as status symbols but as machines that put the fun back into driving by a re-evaluation of what’s really important in a car. It’s a philosophy that Murray has followed all his long life—he’s now 79—ever since building his first racing car in 1967, a Lotus Seven-like device with a 1,100-cc Ford Anglia engine.

That was in his native South Africa, from where Murray emigrated to the UK in 1967. Taken on by Ron Tauranac at Brabham as a junior draughtsman, he was soon promoted—by new team owner Bernie Ecclestone—to chief designer, which finally meant he got to meet his design hero, Colin Chapman. After Murray had made an impression with the Brabham BT44 during the 1974 season, Chapman offered him a job at Lotus. Murray turned him down. Even then, he just knew that they were both too single-minded to be able to work together.

That self-belief paid off, with Murray being instrumental in Brabham winning two F1 World Championships before he moved to McLaren and helped them secure three more. In 1991, however, he was appointed to lead a team to design McLaren’s first-ever road car: the F1.

Given his respect for Chapman’s ingenuity, it’s no surprise that Murray took the Lotus boss’s famous dictum ‘add lightness’ to the extremes. His target weight for the McLaren F1 was famously 1,000 kg. Production realities—having to use steel brake discs rather than the planned carbon items, among other details—pushed that up to 1,130 kg, still incredibly light for a 240-mph hypercar. More than a decade later, the Bugatti Veyron needed four turbos and four-wheel drive to best its performance. However, it weighs over 1,800 kg whereas the T.50 has come in at 997 kg, so Murray got there in the end.

Even by the standards of the early 1990s, the F1 was very analogue; partly to save that all-important weight but also to keep the driving experience as pure as possible. There are no turbochargers, no power brakes or power steering, and, of course, no traction control. Even the air conditioning was minimised so that it only cools the car’s occupants rather than power being wasted on demisting the windows, a task dealt with by using electrically heated plasma-sprayed laminated glass.

Unfortunately for McLaren, the F1 was launched in the financially depressed years that followed the boom-and-bust of the late 1980s, and it struggled to find buyers—a situation almost unimaginable today. As the actor, comedian, and loyal F1 owner Rowan Atkinson said recently: “For anyone to commit, 30 years ago, to spend £635,000 on the purchase of a road car from a company that had never made one represented an extraordinary leap of faith.” Jay Leno, another long-time F1 owner, has admitted, “I had to talk to everyone I knew before I bought it. It was such a huge amount.” But Jay, Rowan, and every other owner who bought an F1 back in the day and hung on to it has seen their judgement vindicated, with standard F1 road cars currently valued between £14 million and £20 million—and upgraded or the race-spec versions worth even more.

It's hard to overstate the impact that the F1 made on its launch in 1993. Although it was relatively conventional-looking for a hypercar—a deliberate choice by Murray, who drafted in noted designer Peter Stevens to shape it—the F1 featured a whole raft of innovative features. Some were immediately obvious, such as the central driving position flanked by two passenger seats, which optimised the pilot’s view and ability to position on the road; others less so—the infamous gold foil-lined engine bay, for example, to reflect heat, or the use of titanium for the main exhaust silencer, which also acted as the rear end’s crush structure. Murray went to extraordinary lengths over every aspect of the car, borrowing a whole raft of classics including the Ferrari 250 GTO and F40 from his pal Nick ‘Pink Floyd’ Mason in order to evaluate what he liked and didn’t like about each.

Hard-bitten motoring journalists who were already familiar with seriously fast cars such as the F40, Lamborghini Diablo, and Jaguar XJ220 found they had to recalibrate their mental receptors when they first got behind the wheel of an F1. Yet the irony of this incredible performance—0-100 mph in 6.3 seconds and a top speed around 240 mph—is that it’s derived from an old-school, normally aspirated V-12. Murray had originally courted Honda, which supplied McLaren’s Formula One engines, but it was wary of committing to a new road car unit. Then Murray happened to meet BMW Motorsport’s technical manager, Paul Rosche, and the German company agreed to make a bespoke V-12 just for Murray’s new project.

Having been unimpressed by turbocharged engines of the era, which were still notably laggy under initial throttle inputs, Murray challenged Rosche to produce a compact V-12 producing 550 bhp and weighing no more than 250 kg. The design Rosche came up with actually weighed 266 kg—but it also generated 627-bhp from its 6,064-cc, way over target. Being a BMW engine, it was also untemperamental and reliable, something that was dramatically proven when a McLaren F1 won the 24 Hours of Le Mans in 1995.

Murray had been actively against racing the car, arguing that it was not designed for circuit use, but was pressured into it by customer demand; fortunately, his caution proved unnecessary when, of the seven F1 GTRs entered for Le Mans that year, the top four finished in 1st, 3rd, 4th, and 5th places. Murray has said it is one of his fondest memories: “Winning that race first time out is, in my opinion, more difficult than winning back-to-back Formula One Championships.”

Today, according to the data analysed by a global classic car insurer, the F1 and F1 GTR are the two most collectable cars in the world, ahead even of perennial favourites such as the 250 GTO. That’s partly due to changing demographics—the buyers with the money want the cars they aspired to when they were young, which now means cars of the 1980s and ’90s—and partly because the F1 ticks literally every box: design, technical innovation, performance, racing pedigree, rarity, usability… and the elusive ‘cool factor’ associated with a Murray design (he’s an all-round cool kind of guy, who counted the late Beatle and petrolhead George Harrison among his closest friends and reckons that music has been as important to his life as cars). And yet, while F1 values are already stratospheric, they could still go much higher.

Like any car, of course, the F1 is not perfect; its design is more than 30 years old. Which is why Murray felt moved to create a ‘new’ F1, one that could address the F1’s few niggles—unassisted steering that is heavy at low speeds, a race-type fuel cell that has to be replaced every few years—and move his quest for perfection even further on. The result was the T.50, which debuted (after a Covid-19 pandemic-induced delay) in August 2020. Superficially, in its cab-forward design with central driving position and general proportions, it looks a little like an F1 and it is very similar in size, being just 60 mm longer and 30 mm wider. It also features a normally aspirated V-12 engine, like the F1.

This time around, the V-12 is by Cosworth. It has a capacity of 3,994-cc and is the lightest, most power-dense, and fastest-revving V-12 ever fitted to a road car. Aside from its astounding 12,100 rpm red line, 661 bhp, and 353 lb-ft of torque, perhaps its most incredible feature is the ability to rev to the limiter from idle in just 0.3 seconds. And yet the T.50 will accelerate cleanly in fifth gear from 20 mph to 186 mph and go on to a top speed in sixth of about 230 mph, depending on gearing.

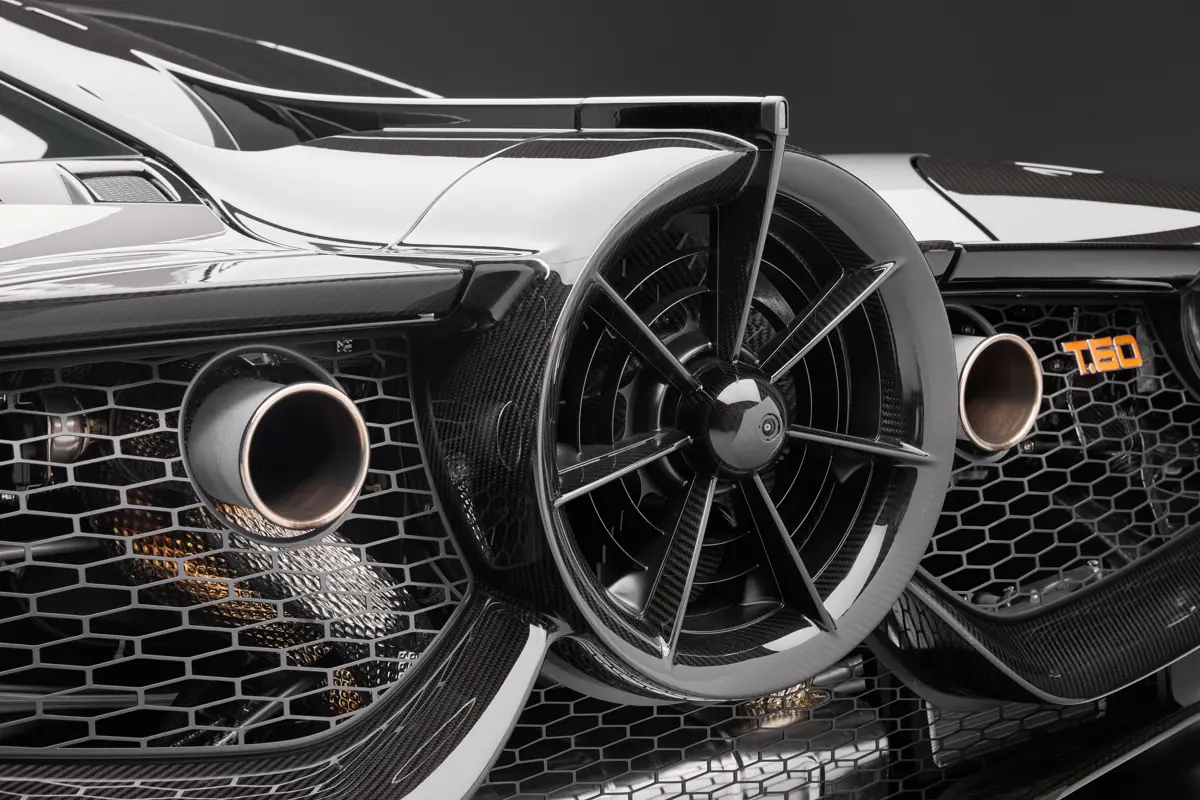

Enough of the Top Trumps statistics. Aesthetically, you can’t miss the huge rear-mounted fan, which instantly recalls Murray’s successful but abortive Brabham BT46B Formula One ‘fan car’ that had just one outing, at the Swedish Grand Prix in 1978. A classic piece of Murray lateral thinking, the Brabham’s fan was ostensibly there to pull cooling air over the horizontally mounted radiator above its Alfa Romeo flat-12, while also just happening to create downforce. Other teams protested that it broke the rules, particularly since it won the Grand Prix and was clearly a game changer, and it never raced again.

The similar-looking fan on the T.50 might therefore be dismissed as a retro-themed gimmick but nothing could be further from the truth. The T.50 uses revolutionary aero of which the fan is a vital part, sucking air along the car to add downforce. Three-time Indy 500 winner Dario Franchitti, who came on board with Murray to develop the T.50, recalls that during early testing the fan suddenly switched off mid-corner, “…and trust me, it’s not a gimmick!”

Despite its staggering performance and roadholding, the T.50 also features all the comforts that today’s drivers have become accustomed to. There’s power steering (to help with parking; it declutches above 15 mph), modern air conditioning, a 10-speaker and 700 W audio system—even, whisper it softly, an infotainment screen. While not many T.50 owners are likely to use their cars every day, it would be no hardship to do so. It is, just as Murray envisioned, like an F1 but better.

After a rocky start, McLaren ended up building just 106 examples of the F1, while there were even fewer of the T.50 made, the 100-strong production run having ended this summer. List price of the T.50 was £2.36 million plus taxes but such was the demand that every car was sold within 48 hours of the global unveiling—and the example to be offered by RM Sotheby’s in Abu Dhabi this December, the first T.50 ever to come to auction, is expected to fetch much more.

Gordon Murray says that one of the reasons he created the T.50 was because F1s had become so valuable, owners were becoming scared to use them. The T.50 would be an even better car, he argued, yet cost much less than an F1 in today’s market. Whether time will bring them closer together in value remains to be seen. Ladies and gentlemen, place your bets…

OWN GORDON MURRAY’S MASTERPIECES

1994 McLaren F1

An exceptional opportunity to acquire the most celebrated supercar of the modern era will present itself at Abhu Dhabi Collectors’ Week on 5 December as chassis 014—the 14th of just 64 road-specification examples of the McLaren F1—goes under the hammer.

Delivered new to the Brunei Royal Family and first finished in Titanium Yellow over black, this hugely significant example later returned to McLaren’s Woking factory in 2007, where its livery was changed to Ibis White and it was fitted with the exceptionally desirable High Downforce Kit and LM-specification interior. Complemented by its original Facom tool chest, it is expected to sell for in excess of $21 million.

The 1994 McLaren F1 will be sold during Abu Dhabi Collectors’ Week on 5 December. Visit rmsothebys.com for more information.

2025 GMA T.50

This year’s Abu Dhabi Collectors’ Week marks the first time a GMA T.50 has ever been publicly offered at auction. This spectacular car is the 35th of only 100 examples produced and is beautifully presented in Harrier grey with gloss carbon accents over a Charcoal Alcantara, Chromite Black, and Matrix Orange leather interior.

The car is accompanied by a four-piece fitted luggage set, a tool chest, and diagnostic computer, while its odometer shows just 217 km since leaving the factory. It offers the first opportunity to acquire Gordon Murray’s groundbreaking reinterpretation of the McLaren F1 at public auction and is expected to fetch in excess of $5 million.

The 2025 GMA T.50 will be sold during Abu Dhabi Collectors’ Week on 5 December. Visit rmsothebys.com for more information.

GMSV S1 LM

Headlining this year’s Las Vegas auction offerings is arguably Gordon Murray’s most exciting design—a fusion of the cutting-edge technology and space-age materials of the groundbreaking GMA T.50 with the styling and presence of the McLaren F1 GTR. The GMSV S1 LM is the best of all possible worlds, powered by a 4.3-litre GMA Cosworth V-12 mated to a six-speed manual gearbox and clothed in evocative bodywork inspired by a legend.

One of five examples commissioned to commemorate the GTR’s stunning victory at the 1995 24 Hours of Le Mans and the only available for acquisition, this sale offered an unparalleled opportunity to participate in the specification, testing, and ownership of arguably the world’s hottest supercar.

The GMSV S1 LM sold at the Las Vegas auction on 21 November. Visit rmsothebys.com for more information.