The extraordinary life of the Chevrolet Corvette is unmatched in American automotive history. In 1953 it was the first production sports car to come out of Detroit. Today, 72 years later, the name lives on in the eighth-generation mid-engined C8 which, in ZR1 trim straight from the showroom, will go from zero to 150 mph in under 10 seconds.

Along the way, the Corvette has built a massive following of knowledgeable enthusiasts. Passionate collectors have hungrily tracked down the special ones: the factory show cars, the development prototypes, cars with triumphant race history, or past celebrity ownership.

But there is one Corvette they have never been able to buy: Project XP-64. It is a pure factory race car, and the only one in existence. Since its creation more than six decades ago it has never been sold. It is the holy grail.

Now, after spending long silent years in the Indianapolis Motor Speedway Museum, emerging only occasionally to be shown at public events, it will be sold at RM Sotheby’s Miami auction on 27-28 February. The guide price is between $5 million and $7 million.

The fascinating story of XP-64 is inextricably linked with one man, Zachary “Zora” Arkus-Duntov. Of Russian-Jewish extraction, he escaped from Europe to the USA during World War II and set up in business as an automotive engineer, later racing at Le Mans for Allard and Porsche. When he saw the original six-cylinder Corvette at General Motors’ Motorama show in New York in 1953, he realized that its potential was not matched by its performance. So he wrote to Chevrolet’s chief engineer Ed Cole, who had overseen the Corvette’s creation, and offered his services to develop and improve the car. Cole hired him at once.

As a man who had raced in Europe and was familiar with British and Italian race car thinking, he brought a fresh perspective to GM’s Americentric approach. After initial excitement at its introduction, Corvette sales were not doing particularly well, and at one point the company’s axe hung over the car. Duntov knew that an enhanced specification, plus exposure on the race track, were what the Corvette needed.

By 1955, under his direction, the Corvette’s original straight-six had been replaced by a V-8, and roadholding and handling had been improved. But the top brass at GM disapproved of getting involved in racing. If it left privateers to run their own cars, the argument went, the company could take kudos from their success; but it would not be harmed by their failures. But Duntov had an ally in Ed Cole, by now Chevrolet’s general manager, and another in GM’s head of design Harley Earl. Persuading GM management that wins on the track would be a powerful marketing tool for the Corvette, he took three near-standard cars to the 12 Hours of Sebring in 1956. One finished 9th and won its depleted class; two retired.

Three lightened and dressed-up Corvettes were then built, called SR-2: they were basically show cars, although one was raced by Harley Earl’s son Jerry. But what Duntov wanted was a pure sports-racing car which could race on equal terms with, and maybe beat, Jaguar’s D-Type and Ferrari’s 250 TR. That meant he had to start from scratch.

Duntov wanted to build a three-car team for the 24 Hours of Le Mans. But when the Chevrolet bosses finally gave their approval in September 1956 it was for just one car—and it had to be ready for Sebring in Florida in March. In a hastily walled-off corner of the Chevrolet Engineering Center Duntov gathered a small, hand-picked team. In strict secrecy they worked around the clock on what would officially be called the Corvette SS, although internally it was known by its styling design number, XP-64.

Duntov knew that weight and aerodynamics were major factors in creating a car that could compete with the best that Europe could offer. As the basis of the car, he wanted a tubular space frame, which would be light and very stiff. His final design closely followed the frame of the Mercedes-Benz 300 SL, using chrome-molybdenum steel tubing, and weighed just 82 kilograms (180 pounds). The fuel-injected Corvette V-8 engine retained the production car’s 283 cubic-inch capacity, but was lightened with aluminum cylinder heads, and breathing was improved to give a higher rev range. Suspension was by coil spring/damper units all round, with de Dion tube and chassis-mounted quick-change diff at the rear. The massive aluminum brake drums were finned to aid cooling, and each had its own vacuum servo. The car rode on Halibrand magnesium knock-off wheels.

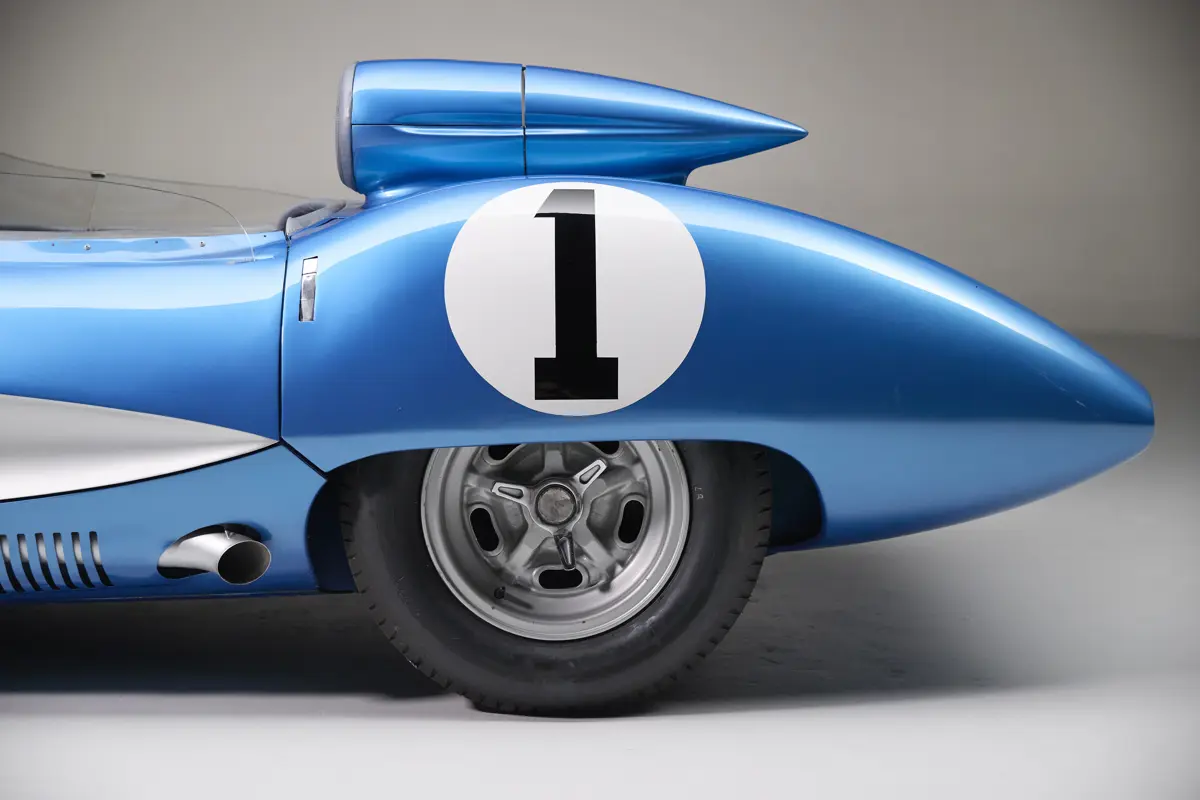

Meanwhile the Chevrolet Styling team had come up with a sensational shape for the car, with a low nose, bullet-shaped headrest and long, tapered tail. The bodyshell was then created in magnesium to save more weight, and both the front and rear sections were hinged to open completely. At the front, a grille echoing the toothy equivalent of the production Corvette provided a useful link to keep the marketing men happy. When it was finished the car was compared in the wind tunnel with a borrowed D-Type, and its aerodynamics were found to be almost the same. Its weight, at 841 kilograms (1,850 pounds) was some 45 kilograms (100 pounds) lighter than the Jaguar.

Before the single XP-64 was completed a test car was built up—the “Mule”—with the same chassis and suspension under a rough glassfibre body to evaluate all the components. In 2,000 miles of testing valuable lessons were learned.

The whole project—from approval through design and build—was completed in five months. According to Chevrolet records the little team plus the styling department clocked up over 16,000 hours; that probably failed to take account of many all-night stints. Thanks to their extraordinary efforts, the car was ready—just—for the 12 Hours of Sebring.

The Mule was sent ahead to Florida while, inside the truck carrying XP-64 the 1,200 miles from Detroit to Sebring, the team worked away to finish as many details as they could. While waiting for it to arrive, Duntov asked both Fangio and Stirling Moss to try the Mule. Almost at once Fangio lapped in 3 minutes and 27.2 seconds, equalling Mike Hawthorn’s lap record from the previous year in a D-Type. Moss quickly turned in 3 minutes and 28 seconds and said that, given a few more laps, he could have carved a couple of seconds off that. Clearly, the recipe was there for one of the world’s fastest sports-racing cars.

In the race XP-64 was driven by the experienced American John Fitch and the veteran Italian Piero Taruffi. It suffered from braking and electrical troubles which could all be blamed on lack of development time. Stifling cockpit heat within the magnesium shell was also a serious problem. Eventually the car was stopped by a rear suspension joint failure. But the speed was clearly there, and a reassured Ed Cole gave the go-ahead to build a three-car team for Le Mans.

Then came the fatal blow. The members of the Automobile Manufacturers Association, the industry body to which all the major American car manufacturers belonged, voted to instruct its members to “take no future part in racing, and refrain from suggesting speed in passenger car advertising.” Ironically, the prime mover in this was GM’s president Harlow Curtice. At once the command came down from on high: scrap every piece of the whole XP-68 project. Now its potential would never be realised.

Somehow, Zora Arkus-Duntov managed to evade the order to destroy both XP-64 and the Mule. The usual fate of most prototypes and experimental cars was a one-way trip to the crusher, but he moved XP-64 from location to location, determined to keep it “off-inventory” and away from the bean counters. The Mule later ended up in the hands of GM styling chief Bill Mitchell, and became the basis of the Sting Ray prototype.

As for XP-64, behind the scenes Duntov could not forget his brainchild. In December 1958 he sneaked it to GM’s Arizona proving ground and lapped the five-mile oval at a blinding 183 mph. For a while GM occasionally allowed it to be brought out for public appearances, like the inauguration of the Daytona track in 1959. But eventually GM decided it did not want a redundant oddball hanging around, and ordered Duntov to dispose of it.

Determined to keep it intact, Duntov offered it to the Indianapolis Motor Speedway Museum, which became its home for the following 59 years. In 1987 it was refreshed and flown to California for Chevrolet’s 75th anniversary at Monterey. Duntov was there to see it, and so was John Fitch. Other outings included the Corvette’s 70th anniversary celebrations at Lime Rock.

And now, for the first time in its life, it is being sold. It is perhaps the most charismatic and historically significant Chevrolet Corvette ever built. Zora Arkus-Duntov would be pleased that now it can be used, enjoyed, and cherished by someone who is, as he was, a true Corvette believer.