The record books show that this Mercedes-Benz W 196 raced only twice in period: a non-championship event in Argentina in January 1955, and the Italian Grand Prix later that year. But now consider this: having made its

debut in the hands of legendary five-time World Champion Juan Manuel Fangio, chassis 00009/54 was then driven in its second and final race by Stirling Moss, Fangio’s heir apparent and the man who would replace him as the sport’s acknowledged benchmark. So, two races—one with Fangio and one with Moss. Sometimes quality really does beat quantity.

Across the long history of grand prix racing, the return of Mercedes-Benz to top-flight competition in the 1950s after a 15-year absence was only a brief moment in time, but it would create an enduring legacy for the marque and its star drivers. Led by the portly, patrician figure of team manager Alfred Neubauer, the ‘Silver Arrows’ entered 12 Formula 1 points races between July 1954 and September 1955 and won nine of them, carrying Fangio to consecutive Drivers’ titles in the process. Then, mission accomplished, Mercedes-Benz was gone again, withdrawing from motorsport in order to focus its resources on its road cars.

Its success came courtesy of the W 196, which may have lacked the handling finesse of the Maserati 250F, but more than made up for it with sheer power and robust dependability. Designed by a team led by Rudolf Uhlenhaut and Dr. Fritz Nallinger, it was powered by a 2,496-cc straight-eight engine that featured Bosch fuel injection and desmodromic valve gear. The engine was canted over within the tubular spaceframe in order to reduce frontal area, and drove through a rear-mounted five-speed gearbox. Suspension was via double wishbones and torsion bars at the front, with low-pivot swing axles at the rear, while the brakes were inboard drums all round.

Two basic body styles were used: the flowing, all-enveloping Stromlinie, or streamliner; and the pugnacious open-wheeled Monoposto. Intended for use on fast circuits, the streamliners delivered a famous 1-2 for Fangio and Karl Kling on the W 196’s debut in the 1954 French Grand Prix at Reims. They would also be used later that year in Britain, Germany (a single car for Hans Herrmann alongside a trio of Monopostos), and

Italy, plus a non-championship round at AVUS.

Development continued into 1955, when the Stromlinie bodywork would be used only at Monza for the Italian Grand Prix, and all the cars went through a weight-saving program in preparation for the new year. A choice of three wheelbases would be available from the season’s second race (Monaco GP), the shortest of which featured outboard front brakes—a feature that would later be seen on some of the medium-wheelbase cars. As if that wasn’t enough, Mercedes-Benz also launched what would turn out to be a successful assault on the World Sportscar Championship with the 300 SLR (aka the W 196 S), which featured a 3-litre variant of the straight-eight engine.

The team strengthened its driver roster, too. Alfred Neubauer had contacted Stirling Moss in November 1954 to see if he was available for the following season, and the young Englishman duly travelled to Hockenheim in early December in order to test a W 196. He found it surprisingly difficult to drive, and in the book he later wrote with Doug Nye—My Cars, My Career—Moss said: "My feet were splayed wide to pedals separated by a massive clutch housing between my shins. The car rode very comfortably, but everything about it felt heavy. It undoubtedly possessed performance. Its engine was terrific… but the gear change pattern was the reverse of what I was used to, selecting second and fourth by backwards movements, third and fifth by pushing forward."

Although he reflected that driving the Mercedes involved "having to concentrate like hell," he was extremely impressed by the way in which the team was run. Even the smallest details were considered at that Hockenheim test: "As I climbed out of the car, rummaging in my pockets for a handkerchief or rag to wipe my face, a mechanic suddenly appeared, bearing hot water, soap, a flannel, and a towel!"

Moss had already won major races such as the Tourist Trophy by the time he signed for Mercedes-Benz, but 1955 was the year in which he grew from promising youngster to acknowledged ace. Racing for the team in both Formula 1 and sports cars, he established a strong relationship with Fangio that was based on great mutual respect, and Moss’s victories that season in the Mille Miglia and British Grand Prix would become career-defining successes.

His debut with Mercedes-Benz came on 16 January 1955 in the Argentine Grand Prix in Buenos Aires, the first round of that year’s World Championship. The race was held in fierce heat and Fangio outlasted his rivals to take victory, Moss having to be content with 4th place in a W 196 that was shared with Kling and Herrmann after his own car retired.

Two weeks later, Mercedes-Benz returned to the same venue to take part in the Gran Premio Ciudad de Buenos Aires, a non-championship race that was run to Formule Libre regulations. The team was typically

well prepared and entered three W 196s with Monoposto coachwork in which the standard 2.5-litre engines had been replaced by the developmental 3-litre unit that would power the forthcoming 300 SLR. These would be driven by Fangio, Moss, and Kling, while Herrmann had to make do with a Formula 1-spec, 2.5-litre car.

Extra louvres and ducts were cut into the bodywork in an attempt to combat the midsummer heat, and Fangio was entrusted with chassis ’09,’ which had been built late the previous year. The event comprised two 30-lap

heats, with the overall winner to be decided on aggregate times, and Moss led the first race from Fangio and the Ferrari of Giuseppe Farina. Moss was struggling with locking brakes and fatigue, and his rivals eventually got past, Farina later overtaking Fangio to take victory by five seconds.

In the second heat, however, a tired Farina soon wilted and went off the road, leaving Fangio in the lead with Moss close behind. The youngster noted in his diary that "Fangio was slower than me on the mid-speed curves and a bit faster on the fast one, until later when I was about the same." He eventually made it past and went on to win, but the ever-astute Fangio had one eye on the aggregate classification and stayed close enough to take overall victory. Moss finished second in the combined standings and said that he’d learned a great deal from the close-quarters racing with Fangio.

Chassis 09 was subsequently fitted with a Formula 1-spec 2.5-litre engine, but it wouldn’t race again until the Italian Grand Prix in September, which ended up being the final round of the 1955 World Championship. There had been a two-month gap since the previous round in Britain due to the cancellation of the German and Swiss Grands Prix in the aftermath of the Le Mans tragedy; October’s Spanish Grand Prix would also be cancelled for the same reason.

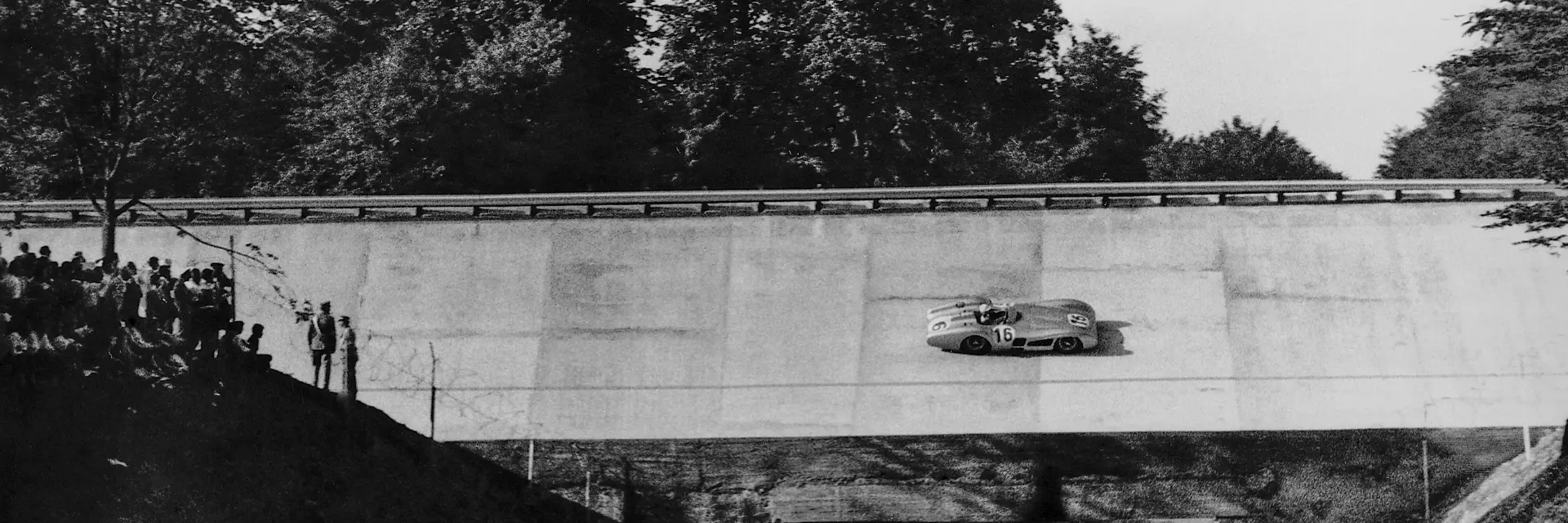

The historic Monza circuit had been much modified since 1954, a new banked oval having been built and the road circuit gaining the Parabolica right-hander to replace the two Vedano corners at the end of the lap. The 1955 Italian Grand Prix would use both layouts, giving a combined lap length of 10 kilometres and speeds high enough to cause headaches for the tyre manufacturers.

Mercedes-Benz arrived at Monza with a variety of cars: long, medium, and short wheelbase; and a choice of open-wheeled or streamlined bodywork. Having tested at Monza two weeks before the race, it had expected the medium-length streamliner to be the best option, but when official practice for the Grand Prix got underway, Moss declared it to be ‘impossible.’ The long-wheelbase streamliner proved to be far more manageable on the high-speed banking, but there was only one of those available and it was reserved for Fangio.

With typical dedication and efficiency, Mercedes-Benz immediately prepared another long-wheelbase streamliner and dispatched it to Monza on its famous high-speed transporter, ‘Das Blaue Wunder.’ This was chassis number 09, and Moss would use it in final practice on the Saturday, the session being extended due to heavy rain during the morning. His time of 2 minutes 46.8 seconds on a still-drying track was the fastest of the day and good enough for second on the grid, only 0.3 seconds behind Fangio’s benchmark from the previous day. Their Mercedes teammates Karl Kling and Piero Taruffi were both in open-wheeled cars and would line up third and ninth respectively.

When the flag dropped at the start of the race on Sunday, Moss tore away into the lead from the middle of the front row and Taruffi came through to make it a Mercedes 1-2-3-4. The Ferrari of Eugenio Castellotti, roared on by the partisan Italian crowd, offered token resistance in the early stages before falling away, but soon the pattern of the race seemed set. Fangio took the lead from Moss and the two streamliners began to edge clear of the open-wheelers, the Argentine maestro running slightly higher on the banking than his young apprentice.

The status quo was broken on lap 19, when Moss came into the pits with a smashed aero screen, which, as he later recalled, "was very small but you could not drive without it. The wind pressure at Monza was enormous—we were doing 160-170 mph round the banking. The first the mechanics knew of it was when I came into the pits pointing at it, and it was not an easy thing to see."

Even so, they removed it and fitted a replacement in less than two minutes, and Moss rejoined in 8th place. He soon passed Bristolian privateer Horace Gould, as well as Mike Hawthorn, setting what would remain the race’s fastest lap in the process, but a piston failed while he was gaining on Jean Behra and he was forced to retire. Kling retired not long afterwards, but Fangio and Taruffi pressed on and finished 1st and 2nd. Italian veteran Taruffi was keen to win on home soil but the wily Fangio was in control as they completed the final lap. "I watched him carefully," he said, "and we finished in formation with me winning by 0.7 seconds."

It was an emphatic demonstration of Mercedes-Benz superiority, Castellotti crossing the line a valiant but distant 3rd. As it turned out, it would prove to be the final outing for the W 196, which had carried Fangio and Moss to 1st and 2nd places in the 1955 Drivers’ Championship. The following month, what had been mooted at the beginning of the season was confirmed: that Mercedes-Benz was withdrawing from motor racing with immediate effect. A ceremony was held at the Stuttgart factory to celebrate its success not only in Formula 1, but also the World Sportscar Championship and that year’s European Touring Car Championship. Then dust sheets were placed over the cars as Alfred Neubauer theatrically wiped away his tears. What was claimed to be a "temporary" withdrawal in terms of Formula 1 actually lasted until 1993, when Mercedes returned as an engine supplier for the Sauber team.

While the W 196 would never compete again, the model’s spirit lived on in the Uhlenhaut Coupé, a brace of spectacular would-be road racers that shared their DNA with both the famed Grand Prix machines and their W 196 S stablemates. Despite their competition pedigree neither car was ever raced, with chassis 00008/55 ultimately going on to become the most valuable model in automotive history after being sold by RM Sotheby's for €135,000,000 in 2022.

As for W 196 chassis 09, it lay dormant at the factory until 1965, when it was thoroughly overhauled by Mercedes-Benz before being donated to the Indianapolis Motor Speedway Museum on 31 May. The date was significant not only for hosting that year’s Indy 500, which would be won by Scottish legend Jim Clark, but also because it marked 50 years to the day since Italian-born American Ralph DePalma had driven a Mercedes to victory in the famous race.

Having last raced at one temple of speed, Monza, it was entirely fitting that it should find a long-term home in another. Still wearing its spectacular streamliner bodywork, it provided a reminder not only of its individual race history with Fangio and Moss, but of a time when the famous Silver Arrows swept aside their rivals from Italy, France, and England. After racing for the German marque during that momentous 1955 season, Stirling Moss was unequivocal in his assessment: "Mercedes were, in my mind, certainly in my era, the greatest team in the world."