When Tom Walkinshaw was entrusted with Jaguar’s Group C programme during the 1980s, he said that winning the 24 Hours of Le Mans—the jewel in the crown of sportscar racing—would take three years. The burly Scot proved to be absolutely right, delivering a famous victory in 1988 after coming up short in the previous two attempts, and whether intentional or not, his prediction mirrored the path that Ford had followed 20 years earlier.

Winning the 1966 24 Hours of Le Mans was Ford’s day of days, an achievement that has been immortalised in history books and on the silver screen, and like Walkinshaw and Jaguar, it came at the third time of asking. Reaching that point had been a long and occasionally troubled process, but everything finally came together during a season in which the GT40 you see here—chassis number P/1032—played a central role.

The origins of that successful Le Mans campaign lay in Enzo Ferrari’s eleventh-hour decision in 1963 to walk away from negotiations that would have resulted in Ford buying a majority stake in his eponymous company. Ford was embarking on its image-boosting Total Performance programme and taking over Ferrari seemed to offer a very useful shortcut to world domination. But while Enzo was prepared to cede some of his power over the road-car business, he came to the last-minute conclusion that Ford’s intention to also control the Scuderia’s competition programme was a step too far.

Story has it that Il Commendatore left numerous members of Ford’s top brass sitting around a table after he got up and walked out of the decisive meeting, and the American company resoled to beat Ferrari with its own competition programme. A Special Vehicles Department was created and a UK base established, and a team of designers working under Roy Lunn—including Eric Broadley, Len Bailey, and Phil Remington—began work on the car that became the GT40.

The scale of Ford’s task should not be underestimated. From 1960 onwards, Ferrari would win Le Mans six times in a row. Its 250 GTO won the International Championship for GT Manufacturers—the World Sportscar Championship in all but name—in 1962, 1963, and 1964. And, just for good measure, Ferrari also added the Formula 1 Drivers’ World Championship in 1961 and 1964, courtesy of Phil Hill and John Surtees respectively.

Bringing an end to such entrenched domination would involve more than simply throwing money at the problem, and Ford initially stumbled out of the gate. A squad of three GT40s was just about ready for Le Mans in June 1964, but little testing had been carried out and all three cars retired.

For 1965, an impatient Ford took control of the factory competition programme away from the UK-based Ford Advanced Vehicles and instead handed it to Shelby American Inc. in Los Angeles. Shelby went to Le Mans that year with two revised ‘Mk II’ GT40s that featured 7-litre Ford V-8 engines in place of the original 4.7-litre units.

Frustratingly, the mistakes of 1964 were repeated. The Mk IIs were clearly the fastest cars at Le Mans but had once again gone into the race largely untested and dropped out early as Ferrari romped to yet another victory. Throughout that season, however, improvements were made in terms of the Mk II’s transmission, brakes, and cooling—and elsewhere there were signs that the times they were a’changing, as Shelby wrestled the International Championship for GT Manufacturers away from Ferrari thanks to its Cobra Daytona coupe.

The big breakthrough came in 1966, the year in which top-level sportscar racing moved away from its experiment with GT-based machinery. The World Championship would instead be fought out by Group 4 and Group 6 sportscars, and by now Ford was fully into its stride. At the season-opening 24 Hours of Daytona, the Mk IIs were out in force, sweeping Ferrari aside en route to a dominant 1-2-3 and setting the tone for the rest of the year.

Next time out at Sebring, P/1032 joined the fray as a Holman-Moody entry for popular veteran Walt Hansgen and a promising youngster by the name of Mark Donohue. The two Americans had come to know each other well while racing in Sports Car Club of America events, and Hansgen had taken Donohue under his wing. They were returning to Sebring having shared a Ferrari 250 LM there the previous year, and had opened their 1966 account by finishing 3rd aboard another Holman-Moody Mk II in that clean sweep at Daytona.

Hansgen and Donohue qualified a strong 4th at Sebring, taking P/1032 around the bumpy airfield circuit in 2 minutes and 58 seconds, just ahead of the Shelby entry of Daytona winners Ken Miles and Lloyd Ruby. Come the race itself, they were forced to pit after only seven laps because the door had flown open, but after that, they had a strong run to 3rd position. That became 2nd when the Mk II of Dan Gurney and Jerry Grant was disqualified for being pushed across the finish line, as Miles/Ruby led another Ford 1-2-3.

Privateer GT40s continued to rack up points in subsequent rounds of the World Championship before it was time for the big one: Le Mans. No fewer than eight Mk IIs were entered—three for Shelby, three for Holman-Moody, and two for UK entrant Alan Mann. Ferrari returned fire with two Works-entered 330 P3s, plus another that was run by Luigi Chinetti’s hugely successful NART outfit.

Having taken part in a couple of test sessions in the US following its Sebring outing, P/1032 was again being run by Holman-Moody and had been repainted in the Mustang shade of Emberglo with white stripes. Sadly, however, Hansgen was missing from the driver roster, having succumbed to injuries suffered in a high-speed stunt during April’s Le Mans Test Weekend. Donohue would therefore be sharing P/1032 with talented Australian driver Paul ‘Hawkeye’ Hawkins, who had won his class at La Sarthe in 1965 aboard an Austin-Healey Sprite.

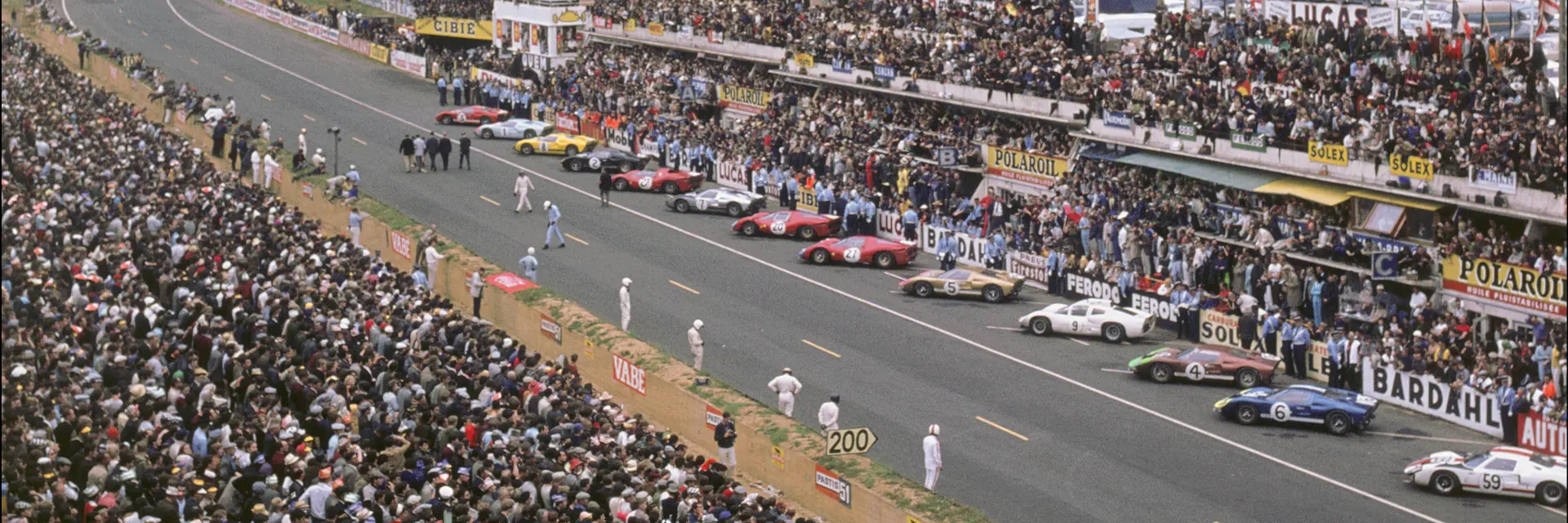

The pair qualified 11th fastest, P/1032 having gained DayGlo green patches in order to help the pit crew identify the car as it went past. Ford locked out the first four positions in the starting lineup and Ferrari was already in trouble, its lead driver John Surtees having stormed off after an argument with team boss Eugenio Dragoni.

Things didn’t get any better for the Italian squad when the race got under way. In what must have been an omen, Henry Ford II himself dropped the flag and the Mk IIs sprinted away into the lead. At the end of the opening lap, Hawkins bought P/1032 into the pits with a broken half-shaft, and it took a while for the Holman-Moody mechanics to replace it.

The car did eventually make it back into the race but soon stopped again in order to have a loose tail section taped down. The fix didn’t work and the panel came away at high speed on the long Mulsanne Straight. P/1032 continued to circulate without it, but was eventually forced out of the race once and for all with transmission problems.

Up front, the Ferrari of Pedro Rodríguez and Richie Ginther had valiantly tried to hold on to the pace-setting Fords of Gurney/Grant and Miles/Hulme, but the Italian challenger retired in the early hours of Sunday morning. It was now Ford’s race to lose, and the pace dropped as the end approached and rain started to fall. The Shelby-entered Mk IIs of Miles/Hulme and Amon/McLaren were in 1st and 2nd, and still on the same lap. As they fell into formation along with the 3rd-placed Holman-Moody car of Ronnie Bucknam and Dick Hutcherson, which was 12 laps behind, a plan was hatched among Ford management to stage a dead heat.

McLaren and Miles duly crossed the line virtually together, but the race organisers ruled that the McLaren/Amon Mk II had covered the greater distance in 24 hours due to having started a few metres behind its sister car. It was a clumsy piece of stage management that robbed Ken Miles of the chance to add victory at Le Mans to his successes at Daytona and Sebring earlier that year, and took some of the shine off things for the New Zealand duo of McLaren and Amon.

But no matter—for Ford, it was a case of ‘mission accomplished’. Three years after being spurned by Enzo, it had beaten Ferrari in the world’s most famous race and was about to embark on its own period of domination—variations of the GT40 would go on to win the 24 Hours of Le Mans four times in a row.

As for P/1032, it was immediately retired from front-line competition and pressed into service as part of Ford’s promotional tour following that breakthrough 1966 victory. It appeared at that year’s Paris Motor Show, then at the Geneva Motor Show in early 1967, and along the way it was repainted in the same colours as the McLaren/Amon Le Mans winner—with the notable exception of white stripes rather than the correct silver.

It eventually returned to the US and was donated to Anton ‘Tony’ Hulman, owner of the Indianapolis Motor Speedway. It first went on display at the Brickyard’s Museum in March 1968 and later spent a number of years in the Early Wheels Museum in nearby Terre Haute.

In the mid-2000s, P/1032 was restored and returned to its Holman-Moody 1966 Le Mans colours, after which it was kept in the IMS Museum’s famous Vault, to be appreciated and enjoyed by guests on VIP tours. It took part in demonstration runs, too—the sight and sound of this famous car instantly evoking that historic 1966 season, when Ford changed the motorsport landscape forever.