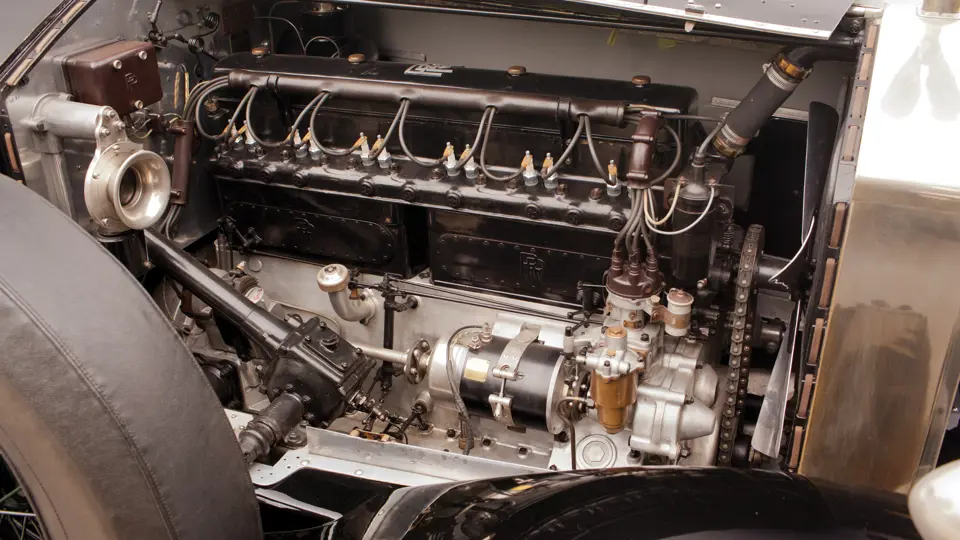

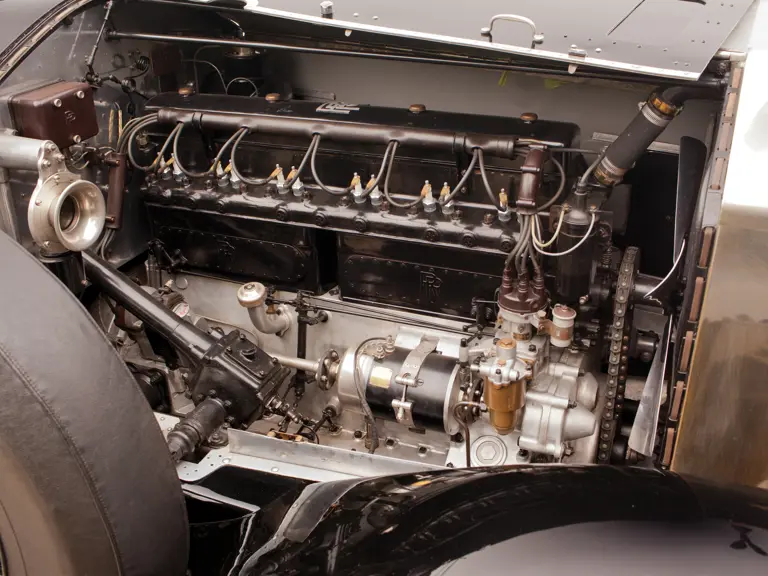

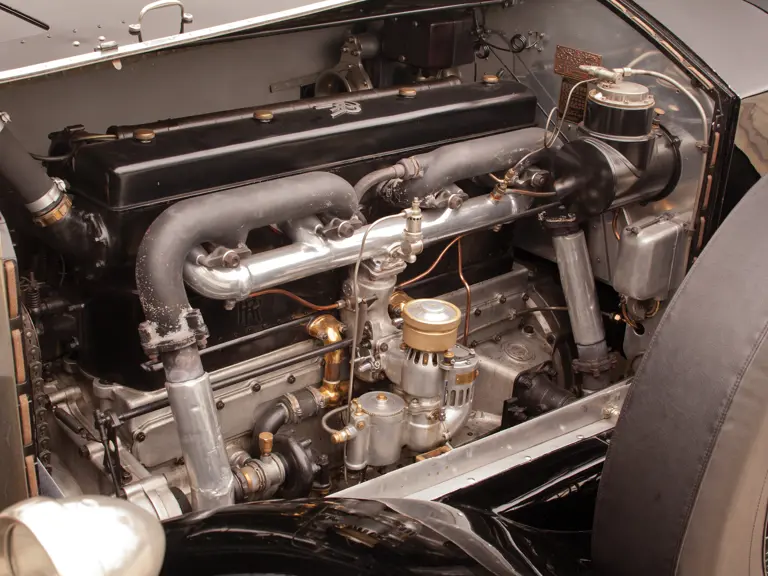

40/50 bhp, 7,668 cc overhead-valve six-cylinder engine, four-speed manual transmission, solid front axle with semi-elliptic leaf springs, live rear axle with cantilever leaf springs, and four-wheel servo-assisted brakes. Wheelbase: 150.5 in.

Before today’s megamarts and big-box stores, the pre-eminent name in American retailing was Woolworth. Frank Woolworth’s chain of five-and-dime stores, where one could buy everything from pantyhose to a hammer and have a slice of apple pie on the way out, made his family one of the wealthiest in America.

A considerable portion of Mr. Woolworth’s estate, which accounted for 1/1,214th of the U.S. GNP at the time of his death in 1919, passed to his daughter, Jessie. Jessie, in turn, married James Donahue, whose rather unglamorous family business (fat rendering) had nonetheless made him considerably wealthy. When Mr. Donahue died of a self-inflicted gunshot wound, Jessie inherited that fortune as well. As such, she became an extremely wealthy lady, which was fortunate for her, because few socialites of the era spent money quite like Jessie Woolworth Donahue.

She had a home on East 80th Street in Manhattan, and there was also a palatial seaside home in the Hamptons, where guests used solid gold cutlery and the pool house alone had seven bedrooms. There was Cielito Lindo, the winter house in Palm Beach, and there were fabulous parties, too many of them to count over the years, that would have made Jay Gatsby green with envy. The Duke and Duchess of Windsor loved Jessie, and she single-handedly funded their lifestyle for some years, considering it a small price to pay for royal friendship.

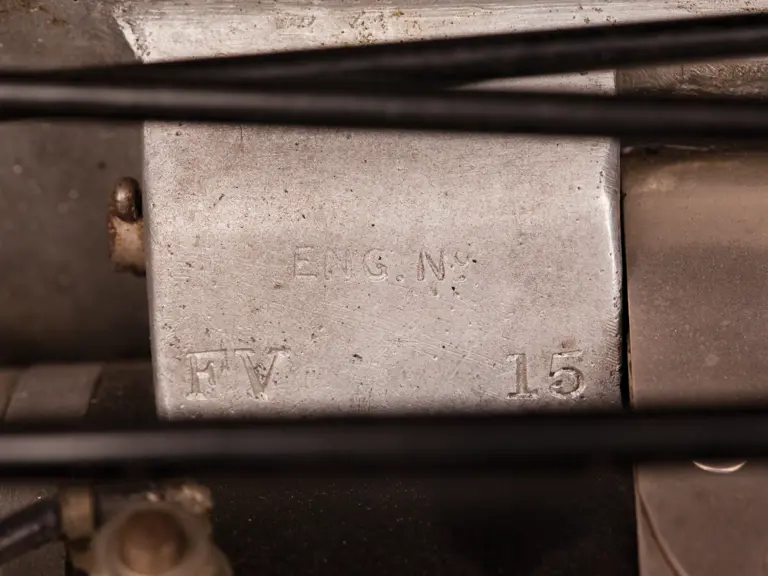

Then, of course, there were the Rolls-Royces. Jessie owned quite a few of them over the years, and they were always custom-built to suit her tastes. Among them was this Phantom I, chassis number 61RF. It was built at the factory in Derby to “Madame’s” exacting specifications, and then it was sent on to Parisian coachbuilder Henri Binder, who constructed an utterly splendid Brougham de Ville body.

This Rolls-Royce was just the thing for its owner’s annual visit to Paris, as it was conservatively trimmed in dark shades and outfitted with Grebel headlights and jewel-like carriage lamps. What little nickel used throughout gleamed against the finish like silver against velvet. The interior was upholstered in the finest of broadcloth and was surrounded by parquet woodwork that rivaled the floor of the finest ballrooms. The effect, with its open driver’s seat, was of an elegant carriage for strictly about-town use by the lady. The rear compartment seated exactly two adults, no more, with no provision for additional passengers or, for that matter, luggage.

Jessie enjoyed her Rolls-Royce in Paris before having it shipped to Manhattan. Upon its arrival stateside, it was fitted with bumpers and rear lighting, as were required for American roads. The car proceeded to remain in its glamorous owner’s stable for several years.

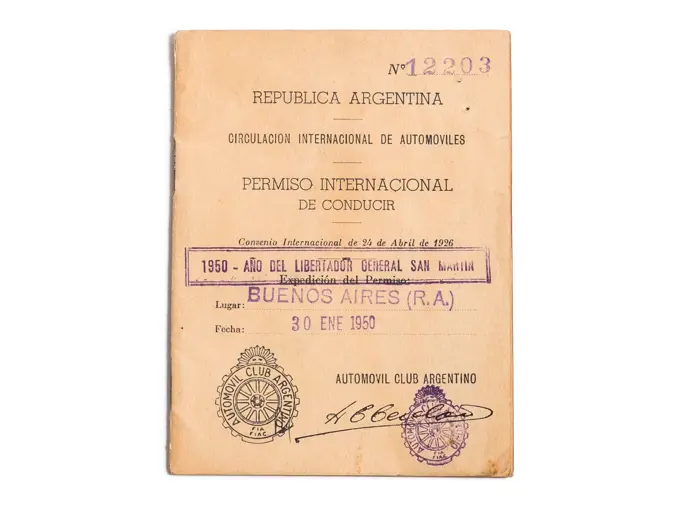

Records from the Rolls-Royce Foundation, copies of which are on file, indicate that the car was acquired on May 23, 1934, by P. Everett Lockhart, of Lockhart International Inc. in New York City. It then passed to Albert Brucklacher, of Williamsport, Pennsylvania, in February 1947; Albert A. Hood, of Wyckoff, New Jersey, in 1952; and F. Lisle McCormick, of Ogdensburg, New York, in 1953. It was eventually exported to the United Kingdom, where it would remain for some time.

Upon its return to the U.S. in 1998, the Phantom I was part of two prominent West Coast collections, those of John Spencer Bradley and David E. Walters, both of whom were parted with the glamorous Rolls only by their passing. In 2004 it was chosen to appear in the Rolls-Royce centenary exhibit, A Century of Elegance, at the Petersen Automotive Museum. Throughout its recent ownerships the car has continued to be well detailed, well cared for, and sympathetically maintained.

While many formal Rolls-Royces of this era survive today, and all are elegant, Jessie Woolworth Donahue’s striking, sporting Brougham de Ville is certainly one of the most elegant. It remains today very much as it was when its original owner first commissioned her Rolls-Royce, and it is a spectacular tribute to what sufficient funds and a silver spoon can create together.

| Plymouth, Michigan

| Plymouth, Michigan