1938 Bugatti Type 57C Atalante

{{lr.item.text}}

$2,200,000 - $2,500,000 USD | Not Sold

{{bidding.lot.reserveStatusFormatted}}

- Displayed at the 1939 New York World’s Fair

- One of the final Atalantes produced; one of only 12 aluminum-bodied examples

- Formerly owned by Al Garthwaite of Algar and John W. Straus of Macy’s

- Known history from new documented by Pierre-Yves Laugier

- Desirable late-production 57C chassis with all original components

- Spectacular French Art Moderne design at its finest

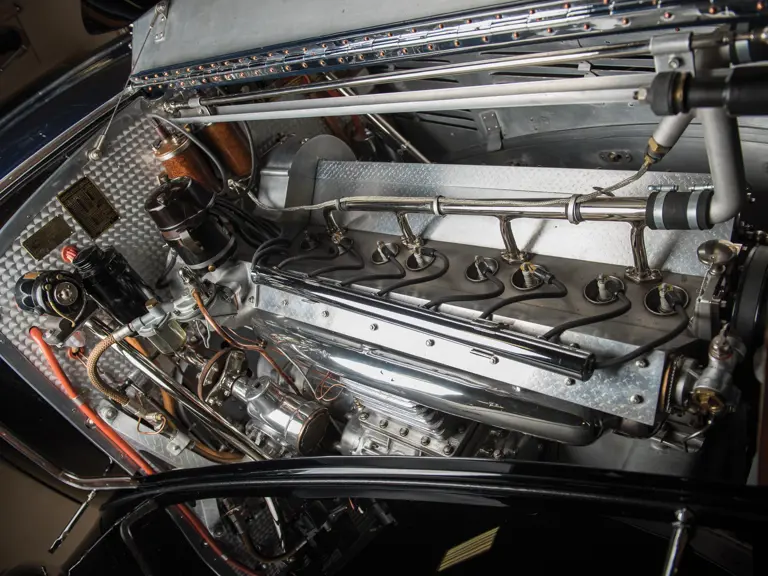

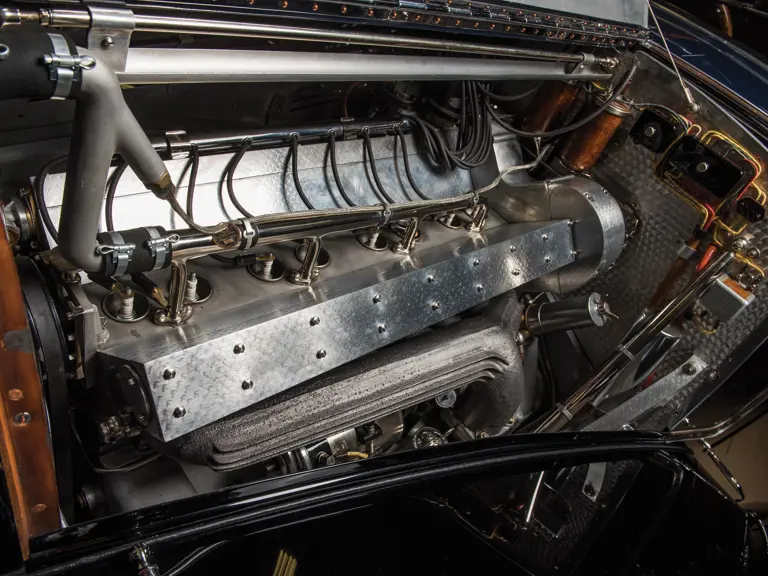

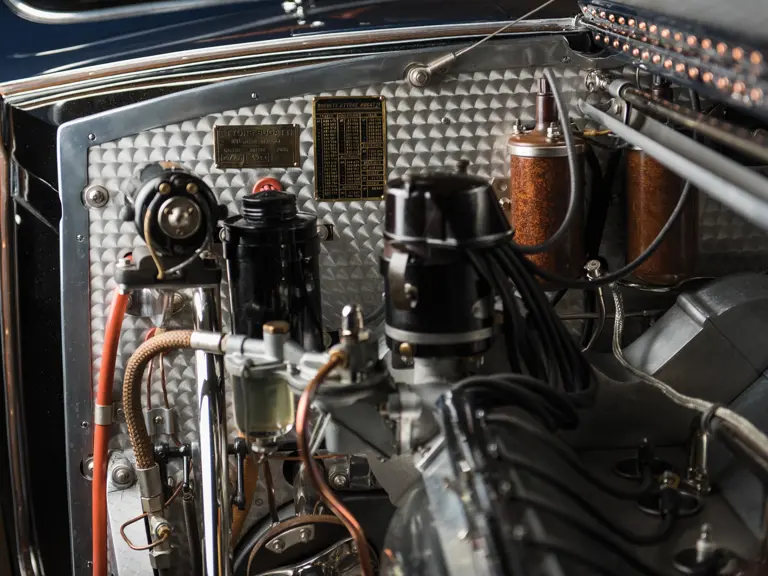

160 bhp, 3,257 cc DOHC inline eight-cylinder engine with Roots-type supercharger, four-speed manual transmission, solid front axle with semi-elliptical leaf-spring suspension, live rear axle with reversed quarter-elliptical leaf-spring suspension, Houdaille shock absorbers, and four-wheel Lockheed hydraulic drum brakes. Wheelbase: 130 in.

THE WORLD’S FAIR ATALANTE

The French Pavilion at the 1939 New York World’s Fair was designed, in typical Gallic brilliance, to show off the best that its country had to offer—and it did so with precision and flair. Arguably, more than any other nation’s exhibit at the fair, it left the most behind in the U.S. in its contributions to art, culture, cuisine, and most particularly in automobiles. Some of the finest custom coachbuilders in France had bodied the country’s best chassis to advanced and spectacular designs, not least of which was the Bugatti on display, carrying the late Jean Bugatti’s stunning Atalante design.

The Atalante embodied everything great about French Art Moderne design: arching fenders, a svelte “notchback” body with a curving roofline, a slanting tail that descended dramatically over the rear fenders, and a wonderfully subtle two-tone color scheme that emphasized its lines. It was the country of France on wheels: bright, modern, spectacular, and proud, and, most importantly for the French Government, it was a stunning contrast to the stolid American designs of 1939. Nothing could beat it for advanced design of chassis, engine, or body. Of the 33 Atalantes produced by Bugatti, only the final 12, including the World's Fair example, were produced with aluminum coachwork. It was the world’s ultimate automobile, and France had built it. Now it was theirs to show off on the world stage, shaking up automotive design on two sides of the Atlantic.

IN THE HANDS OF ENTHUSIASTS

Prior to 1946, the World’s Fair Type 57 Atalante, chassis 57733, came into the possession of early American Bugatti enthusiast Ray Murray. Murray also owned Type 57C chassis 57766, a Stelvio Cabriolet originally delivered new to gentleman racer Nicholas Embiricos. Embiricos had the Stelvio shipped to his residence in Palm Beach, and Murray probably acquired it in 1941 shortly after Embiricos’ passing. This chassis was of the latest and best Bugatti design, with such sought-after late-Type 57 features as Bugatti-Lockheed hydraulic brakes, tubular shock absorbers, and rubber engine mounts, significant changes that deeply improved the car’s riding and handling qualities. Desiring the most potent combination of the lightweight aluminum coachwork and a supercharged Type 57 chassis, of which only five were originally constructed, Murray swapped the two bodies, bringing 57766 to its present and most desirable specification.

In 1947, the now supercharged Atalante was purchased by the legendary Pennsylvania enthusiast Al Garthwaite, most famous as the founder of the Algar Ferrari dealership in suburban Philadelphia. Mr. Garthwaite was an active racer who was deeply involved in early SCCA activities in his spare time and who promoted road-racing extensively throughout the East Coast. Unsurprisingly, the Bugatti became his latest steed, and its first known outing was the Watkins Glen Junior Prix on October 2, 1948. It was also exercised in the 100-mile feature event at the Bridgehampton Road Races on Long Island on June 11, 1949, where the car performed admirably but was waylaid by a broken connecting rod. Repaired, the Bugatti ventured to the Mount Equinox Hillclimb in Vermont on July 29, 1950, and set the eighth fastest time of the day—just behind a brand-new XK 120!

After several years of avid enjoyment, Mr. Garthwaite passed his Bugatti on to a friend and client, Dr. Samuel Scher, a pioneering U.S. collector best known for his sports car racing and stable of Brass Era automobiles. Dr. Scher took the car to the famous New York “garage of stars,” Zumbach’s, for service, and while there it was spotted by John W. Straus. For the Macy’s heir, it was love at first sight, and he had soon acquired the Bugatti from Dr. Scher.

The Straus garage was not so much a collection as an old-school gentleman’s stable that included a fine automobile for every purpose, from the family Duesenberg and a Springfield Rolls-Royce to a Mercedes-Benz 540 K, a Ford Model T, and two Jaguars. At least in the early years of his ownership, it seems that the Bugatti was among the cars that Mr. Straus drove most, running it regularly in the New York area and socializing with Ralph Stein and other enthusiasts of the age. Yet in the early 1960s, he began to move away from his motoring adventures, and the Atalante was parked in a garage in the suburbs; down came the garage door, and the Bugatti was seemingly forgotten. It was not until Mr. Straus’s estate was being settled in 2007 that the garage door was opened again, revealing the “lost” Bugatti, intact and well-preserved under 45 years of dust.

THE RETURN TO NEW YORK

The car was sold to an East Coast enthusiast, who had it sensitively cleaned and returned to operational condition by Sargent Metalworks of Fairlee, Vermont, and then displayed it in the hotly contested Prewar Preservation class at the Pebble Beach Concours d’Elegance in 2007. Afterward, the Atalante participated in the American Bugatti Club’s Annual Meet at Watkins Glen and was shown as part of the special “Barn Finds” exhibit at the Saratoga Automobile Museum in New York.

After changing hands shortly thereafter, the Bugatti was returned to Scott Sargent’s shop for a complete restoration. Pebble Beach Best of Show-winning restorer Scott Sargent, who once looked after the well-known Williamson Bugatti Collection, tackled the job of restoring such an intact, original car with aplomb.

The body’s structural wood was found to be in very good condition, with much of the factory paint still covering the frame. The interior wood, including the dashboard, garnish moldings, and window trim, was in such good condition that it was able to be cleaned, re-veneered, and mounted back into place. The body panels themselves were found to be incredibly original, with the body number 32 still stamped into the fenders, doors, original wooden floorboards, brackets, dashboard, and firewall. Amazingly, the engine, rear end, transmission, and front axle are the original pieces installed at the factory and stamped “57C.”

These original components were carefully dismantled, restored, and put back together, with a thorough rebuild of the engine being undertaken by Gary Okoren and Sam Jepson. Well-preserved original interior components allowed renowned upholsterer Mike Lemire to recreate the distinctive grain and color of the original leather, while O’Donnell Classics refinished the original body panels in a period-correct French Blue and Black combination.

With its restoration completed, the Bugatti made a return to Pebble Beach, where it completed the Tour d’Elegance and earned 2nd in Class in the concours. In its ownership following the Pebble Beach Concours, it has been selectively shown at only a handful of further events, resulting in Best of Show honors at the Saratoga Invitational in 2012 and, in its present care, at the Lake Mirror Classic in 2014.

Nearly seven decades after its debut at the 1939 World’s Fair, the Atalante is presented once more in New York. Again in show-worthy condition, as striking and detailed as when it was completed, it offers the best imaginable combination—the most developed, highly original 57C chassis and the most striking, historic, and last Atalante body.

The World’s Fair Atalante is a showstopper, and certainly the craftsmen who built it would not have had it any other way.

| New York, New York

| New York, New York