The post-war sports car in America is a thing of beauty, and the man almost singularly responsible for recognizing that American audiences would appreciate such beauty and performance was Max Hoffman, for whom the world’s automakers created art in metal for, for over two decades. He was the ultimate muse: a man who inspired beautiful machinery with a simple command, and one that had the resources and influence to back up his inspirations.

It was the drumbeats from Hoffman’s New York office that led to the creation of the Porsche Speedster, the Mercedes-Benz 300 SL and 190 SL, and this car, the BMW 507. BMW would have eventually recognized the performance capabilities of its engineering, or how the American market’s thirst for fast, beautiful open two-seaters had not yet been quenched, but it was actually Hoffman who spurred on the effort, by demanding stylish machinery that would bridge the divide between low-priced MGs, the Porsches, and the pricey 300 SL in his lineup.

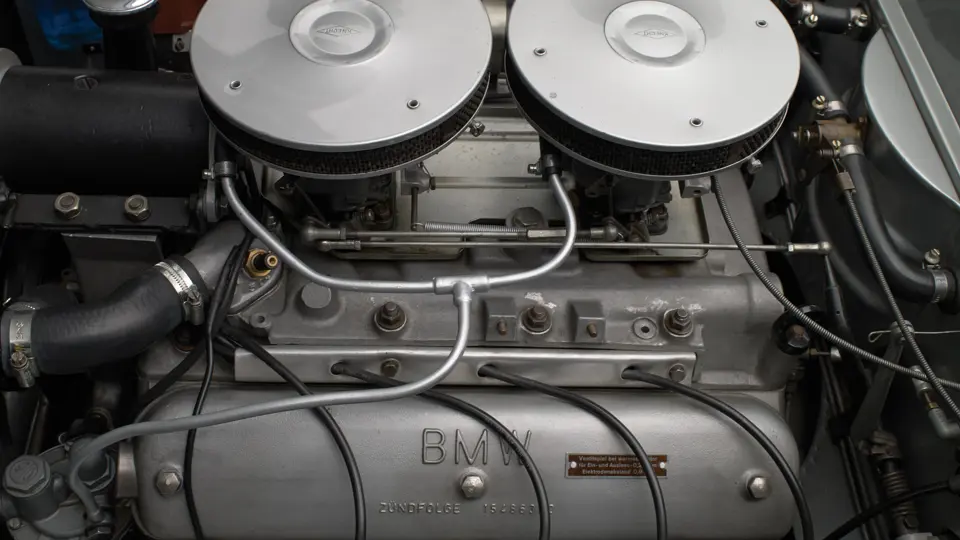

The 507 would utilize the best of Bavaria, with mechanical components sourced from the 502 and 503 series, including a 3.2-liter, overhead-valve aluminum block V-8, which had been improved with twin carburetors in order to produce some 150 horsepower. Like most great automobiles, however, it would not have become a legend if not for its flowing, downright sensuous curves. It was Max Hoffman who had final approval of the design, so he requested the services of Count Albrecht von Goertz, a protégé of famed industrial designer Raymond Loewy, whose futuristic themes for Studebaker in the early fifties had caught Hoffman’s discerning eye. For Hoffman and BMW, Goertz imagined some of the most beautiful lines ever folded into metal.

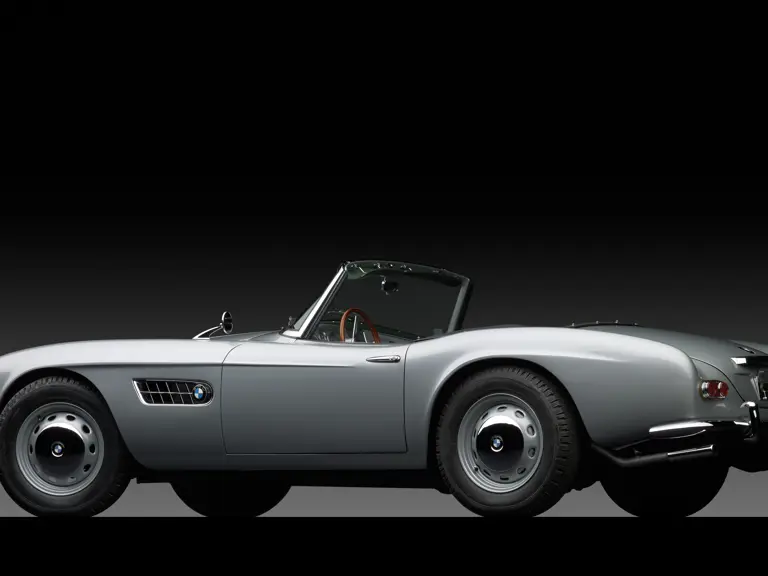

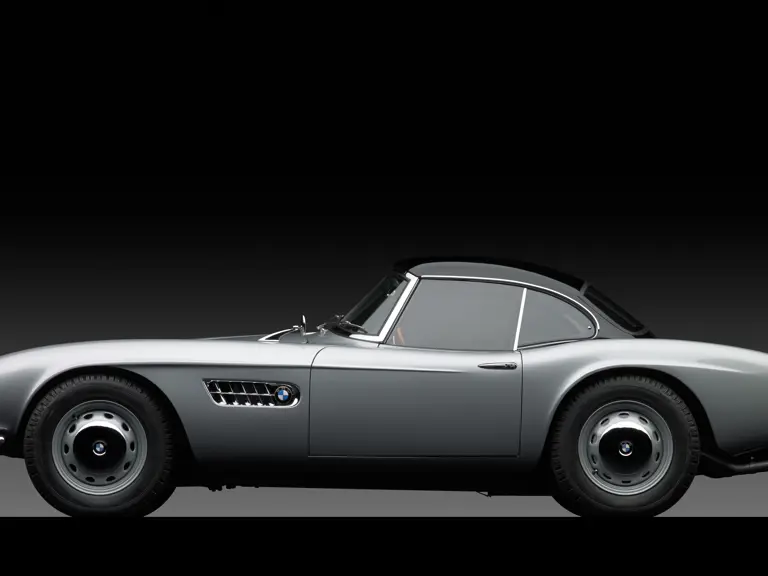

The 507 design had a lightness that was combined with a hint of feline power and unmatched refinement. Its long, sinuous fenders kicked at the rear and swept elegantly towards the front, framing a glamorously stylized version of the traditional BMW “twin kidney” grille, in itself molded and refined, with voluptuous creases that were prominent from every angle. Narrow chrome bumpers did not interfere with the flowing simplicity of the design, but it instead accented its grace. Most prominent to the stylist’s eye are the intricate shark-like ventilation “gills” along the front fenders, which echo those on the Mercedes-Benz 300 SL, which was Hoffman’s earlier inspiration. It is a reminder of the visionary muse behind Goertz’s art, and it is a stylistic feature that is still visible decades later in many of BMW’s sports cars, beginning with the Z8.

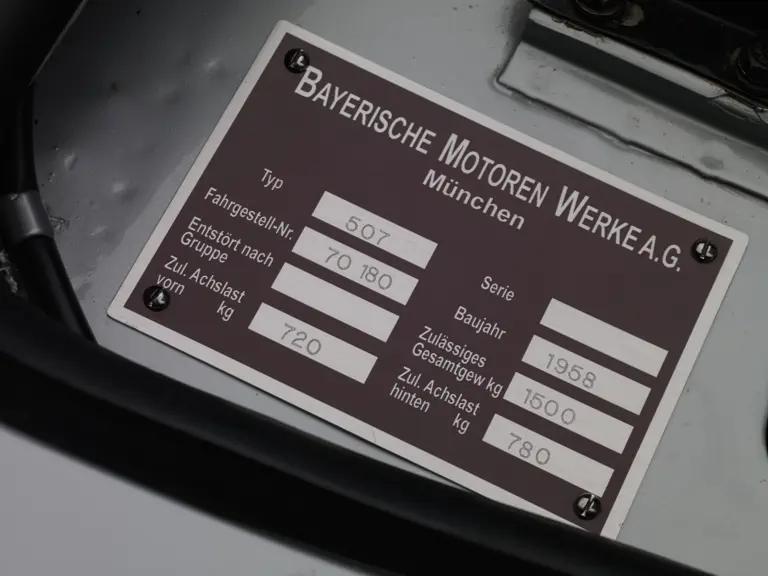

The 507 was hand-built at a price that eventually reached over $11,000, which was a towering sum for a car in the day, and it was discontinued after only two-and-a-half years and 251 examples. Those 251 people looked at the car, soaked up its beauty, and likely forgot the price. Elvis Presley reportedly gave one to Ursula Andress, who was entranced with it. Eventual World Champion John Surtees received a 507 from Count Agusta, the motorcycle manufacturer. The basic lines of the 507 went on to inspire the greatest modern BMW, the Z8, which became its spiritual successor in the carriage houses of the wealthy and stylish.

Offered here is a desirable Series II variant with increased engine output and a little additional space behind the seats, offering those taller drivers a more comfortable seating position. It has been beautifully restored in striking Silver with contrasting handsome Green leather upholstery, making it an elegant, period-correct, and beautifully subtle alternative to the sea of white 507s more often offered. It is presented in excellent overall condition, and it has been nicely detailed, with correct steel wheels fitted and an original 507 factory hardtop. Importantly, the 507’s hardtop was “designed in” by Goertz, and the car is as striking with the hardtop fixed as it is when opened to the breeze.

Most importantly, in a recent road test by an RM specialist, the car started with ease and was superb in operation, with an easy clutch, responsive brakes, and exhilarating performance. Even at 60 mph, it traveled straight down the road, and heading into a curve, it handled adroitly, just as Max Hoffman would have expected of it.

In those days of the new America, as memories of World War II faded and the Baby Boom echoed through streets of prosperity, sports cars became a symbol not just of speed, but also of freedom. The BMW 507 has become an iconoclastic object of that time, and it is at home in history as it is in the garage.

| New York, New York

| New York, New York