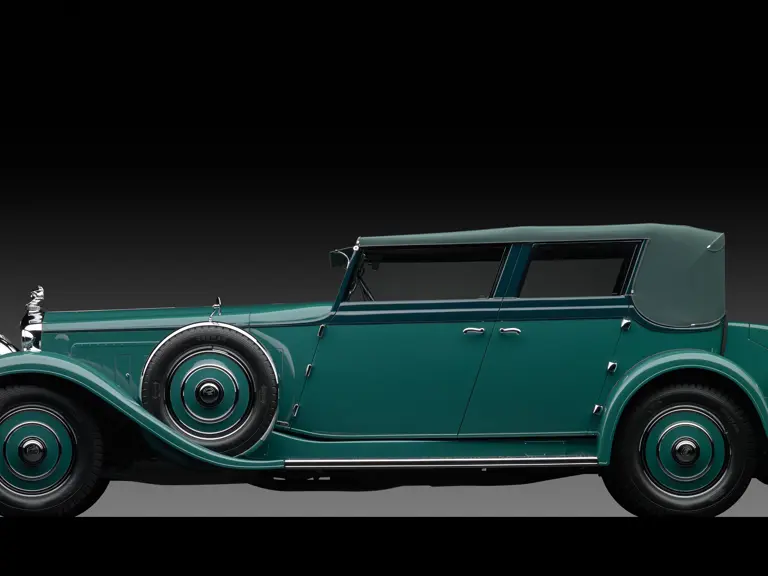

1931 Minerva AL Convertible Sedan by Rollston

{{lr.item.text}}

$660,000 USD | Sold

{{bidding.lot.reserveStatusFormatted}}

- A pioneering example of streamlined automotive design

- The only known Minerva AL chassis with American coachwork

- Purchased new by noted socialite Henry Walker Bagley

- Formerly owned by D. Cameron Peck and Gerald Rolph

- Award-winning concours restoration

Design critic Charles Richards wrote in 1929 that “the highest expression of modernism is the highest expression of eccentricity.” Richards was talking about furniture, not automobiles, but designers in the country’s coachbuilding houses seemed to agree.

There were exceptions, like show cars from LeBaron—the Aero Phaeton on a Lincoln chassis, with its torpedo of polished aluminum—and Brewster—the Rolls-Royce “Windswept” Coupe that took New York by storm. Most of the time, however, those designs failed to impress the majority of the blue-blooded buyers. In a time of worldwide financial calamity, to drive out-and-out avant-garde creations was not just economically unwise, it was, to many of American coachbuilding’s best customers, the height of bad taste. If one wanted to be at the cutting edge, it had to be handled gently and elegantly.

Thus, streamlined design crept into American automobiles slowly but surely. One of its first expressions was a Minerva AL chassis that was dressed by the Rollston Company. Rollston had a long-lived reputation as New York City’s king among coachbuilders, but they were not ordinarily a style setter. So, when Henry Walker Bagley and his Minerva came calling, they built him a convertible sedan. This time, however, they put a slant on things.

THE BAGLEY MINERVA

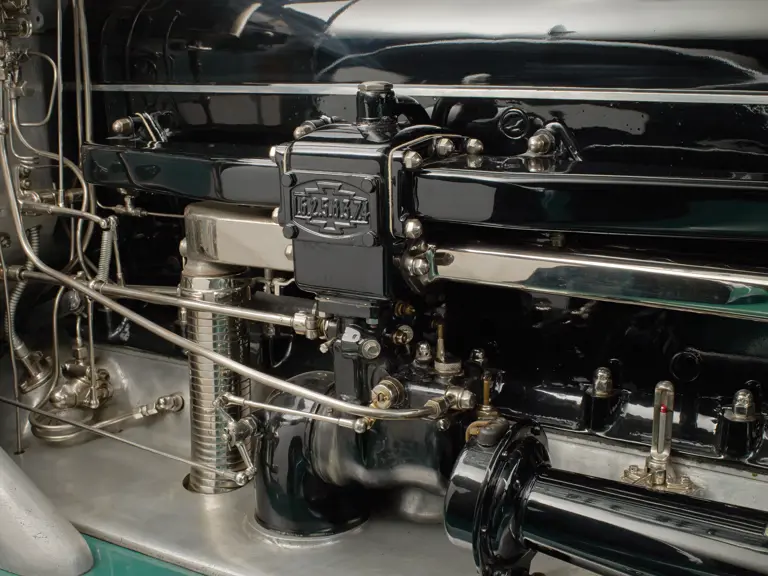

Bagley and his wife, tobacco heiress Nancy Reynolds, chose for their personal conveyance Belgium’s finest luxury car, the Minerva AL. The 153½-inch wheelbase AL featured the most developed version of the Belgian automaker’s sleeve-valve engine. This innovative design replaced conventional poppet valves with mechanically actuated steel sleeves, which moved up and down within the bore and within which the piston reciprocated. When the ports in the two sleeves aligned with the exhaust port, the exhaust cycle was underway. Intake worked according to the same principle. The action of the sleeves moving up and down was caused by a fairly conventional crankshaft, which acted on roller bearings that were affixed to arms that were attached at the bottom of each sleeve.

The design was complicated but peerlessly silky-smooth, and the AL, which displaced 6,625 cubic centimeters over eight cylinders, was also powerful; this was everything that one wanted in a luxury car.

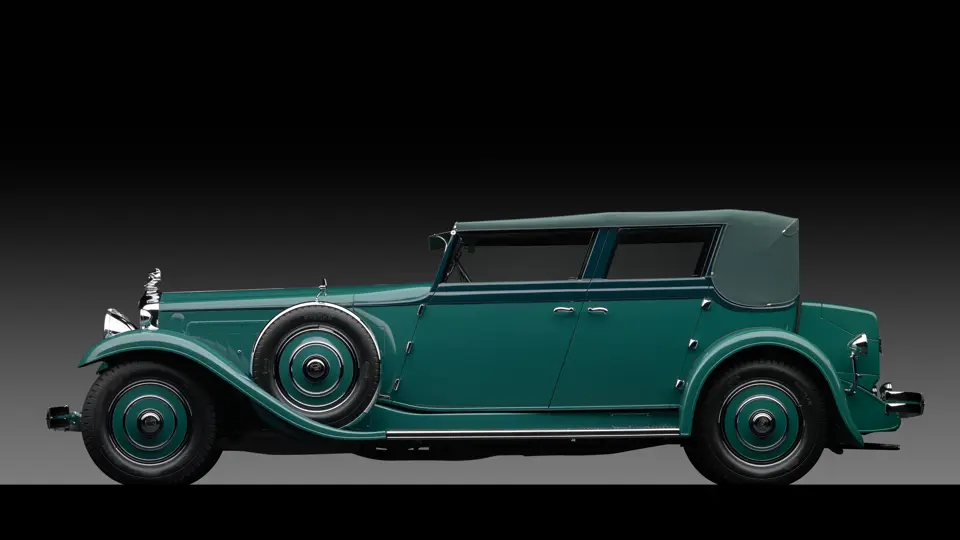

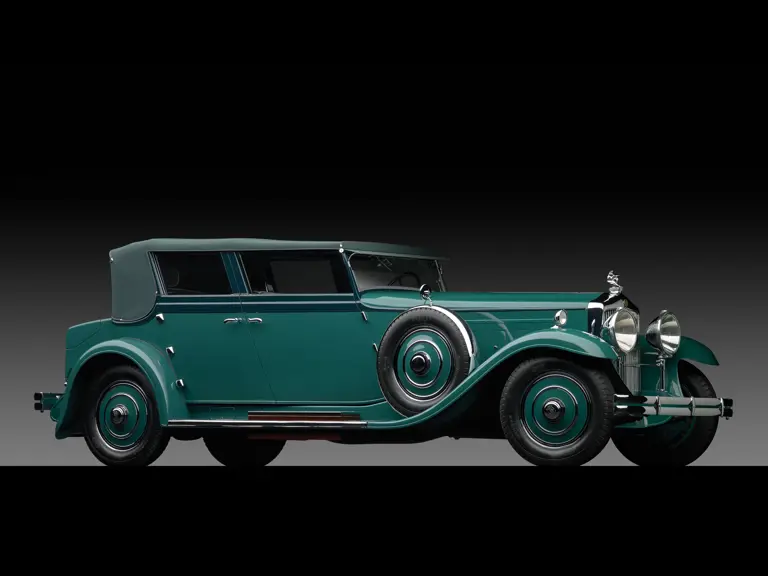

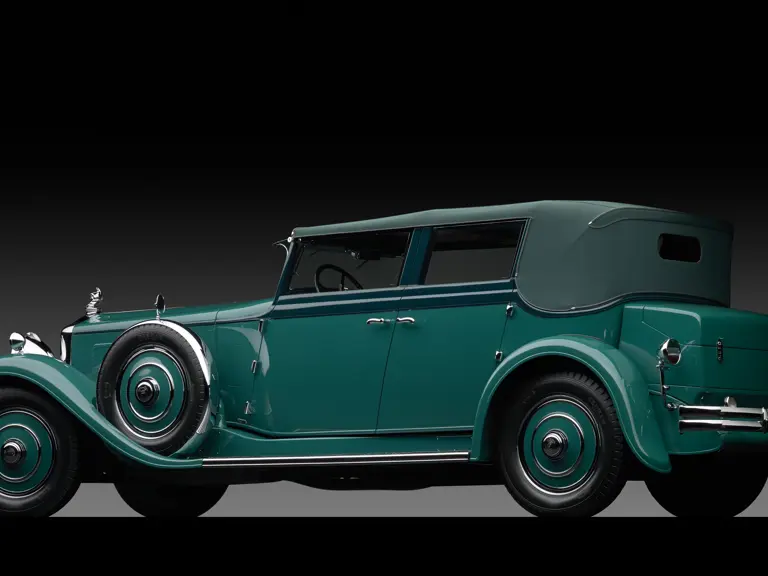

Rollston’s body for this silent motor car was, in many ways, a traditional convertible sedan, with elegant but dignified interior appointments and a fully insulated soft top, which made the car a formal sedan when it was raised and transformed it into an airy convertible when it was lowered.

What distinguished this car was that the doors were angled backwards at a dashing rake, and they were mounted on hinges carefully engineered to suit. This “slant door” design had been tried before by Hibbard & Darrin, of Paris, and Brewster, of Long Island, both on Rolls-Royce chassis. It was, in all likelihood, the Brewster “Windswept” Coupe, shown in New York in 1930, that inspired the Bagley Minerva’s design.

Rollston’s genius, however, was in improving upon the lines by matching the windshield, pillars, and even the shapes of the windows to the rake of the door lines. As with all great design, colors were used to guide the eye home, with a flow of darker paint along the beltline, accentuating how the design seems to be pushed rearward, by the force of its own drama. It is a cliché to say that a design makes a car “look fast when it is standing still.” In this case, the idea was not to make the car look fast; the idea was to accentuate the power suggested by its heft. Perfection is in the details, and even the Minerva mascot atop the radiator, a head that is mounted far back on an elegant neck, recalls the angles that define this car.

The Minerva was eventually acquired by pioneering collector D. Cameron Peck, of Chicago, and it was later passed through the hands of Fred Bultman and Dr. James Dees. It was acquired in 1967 by well-known enthusiast and collector Gerald Rolph, then of Texas. Mr. Rolph was among the Minerva’s most passionate connoisseurs, penning the definitive history on the AL for the March/April 1973 issue of Antique Automobile magazine. Naturally, his own Rollston-bodied car was featured on the magazine’s cover.

Mr. Bagley’s Minerva remained in the Rolph Collection for an astonishing 30 years, before being sold in 1997. It was next acquired by Charles Morse, of Washington State, and with its original restoration “of age,” it received the concours-quality restoration that the AL still wears today. Following its completion, the Minerva was awarded Best in Class at the Pebble Beach Concours d’Elegance, as well as receiving awards at Meadow Brook, Amelia Island, and the Louis Vuitton Concours.

Norman Bel Geddes, the renowned industrial designer, stated in 1932 that the beginning of the decade would be recalled as such: “In the midst of a world-wide melancholy owning to an economic depression, a new age dawned with invigorating conceptions, and the horizon lifted.” This Minerva marks that moment, as the automotive bellwether of the streamlined age.

| New York, New York

| New York, New York