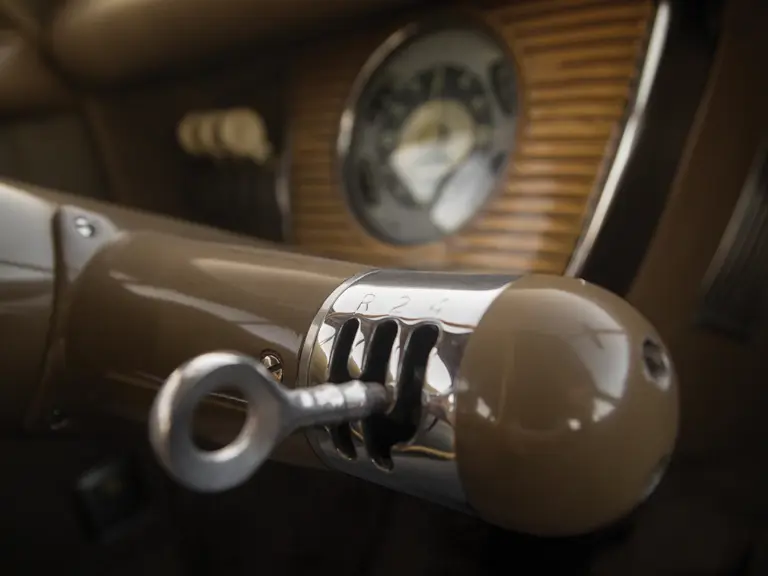

166 bhp, 335 cu. in. OHV horizontally opposed six-cylinder engine, Tucker Y-1 four-speed pre-selector transmission, four-wheel independent suspension, and four-wheel hydraulic drum brakes. Wheelbase: 130 in.

Road & Track magazine’s founder, John R. Bond, once said, “A little knowledge about cars can be dangerous.” Preston Thomas Tucker was an industry veteran with a lot of knowledge about cars, and he used that knowledge to dream bigger than just about anyone else in the U.S. automobile industry after World War II. The reasons why he did not succeed remain controversial, but success is not only measured in dollars and production numbers. It is also measured in lasting memories, and for many, the Tucker 48 remains a rolling symbol of the American dream and one of the most advanced early post-war automobiles.

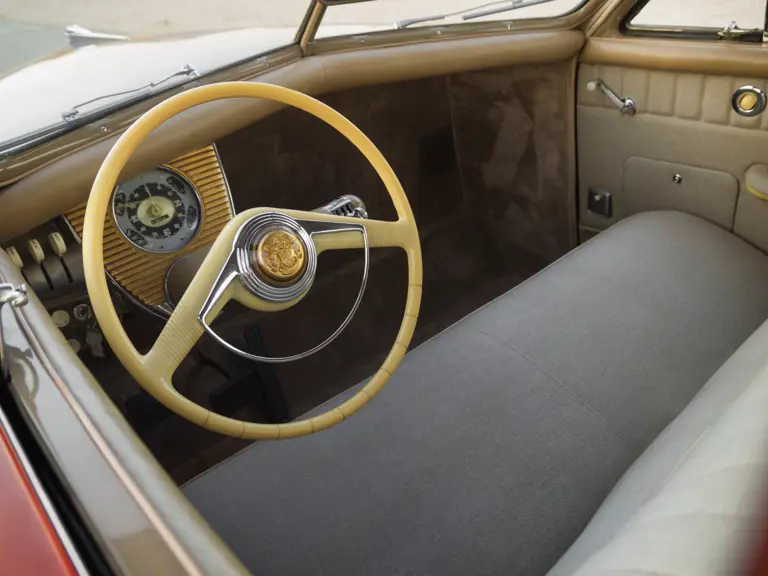

Tucker’s concept for his car was revolutionary. He intended to use a Ben Parsons-designed rear-mounted engine with all-independent Torsilastic rubber-sprung suspension and disc brakes on all four wheels. Drive was to be by twin torque converters, one at each rear wheel. The body design was penned by former Auburn Automobile Company designer Alex Tremulis, and it incorporated numerous safety features that Tucker promoted, including a windshield that would pop out in an accident, a wide space under the dash pad into where front seat passengers could duck before a collision, and a center-mounted third headlight that would turn with the front wheels.

Early in the production cycle, the Tucker saw some of those dreams evaporate. The safety features survived, but the Parsons 589 engine and direct torque converter drive proved impractical. Tucker purchased Air Cooled Motors, a New York manufacturer of small aircraft engines, and reworked their product for water cooling. He installed it in his car, along with a four-speed transaxle borrowed from the Cord 810 and 812.

Eventually, 51 examples of the Tucker 48 were assembled, and of those were the original “Tin Goose” prototype and 50 pilot-production cars. Public acclaim and desire for the new design was at a fever pitch. Unfortunately, it was all for naught. The Tucker Corporation came under the scrutiny of the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission. The wheels of government ground slowly, and by the time Tucker and his executives were eventually declared “not guilty” in early 1950, the public had lost faith and Tucker had lost his factory. The car once nicknamed the “Torpedo” had been, effectively, torpedoed.

A little knowledge about cars can be dangerous, but it can also result in something so full of passion and fascination that it can survive bureaucracy and time to become an icon of its age and the ultimate validation of its creator. It is the American dream on four wheels.

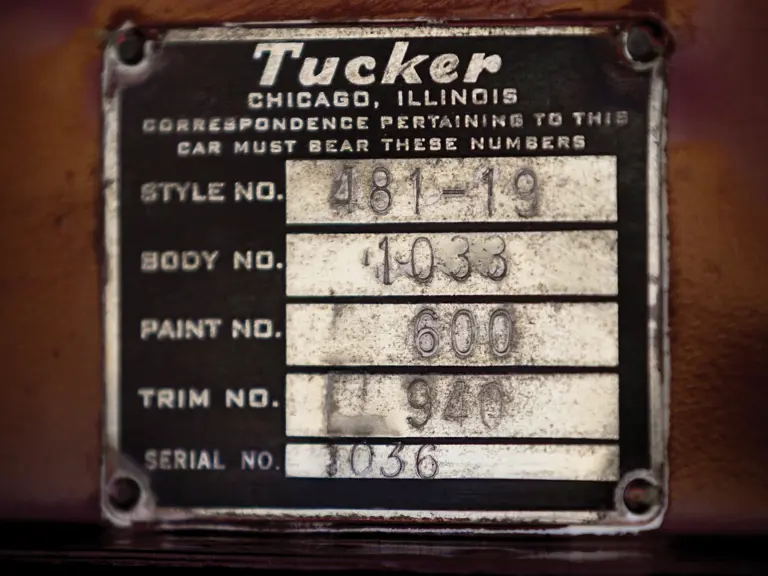

TUCKER NUMBER 1036

A factory report dated October 28, 1948, held in the Tucker archives at the Gilmore Car Museum, indicates that chassis number 1036 had been completed on October 20, with body number 33 and engine number 335-85, and it was one of a dozen cars painted Maroon (paint code 600). No transmission was listed, as it is believed that this was one of the over a dozen Tuckers that remained unfinished and were waiting for transmissions when the factory closed. This is confirmed by the final factory inventory, dated March 3, 1949, which shows the car being in factory building number four with no transmission and having a price/value of $2,000.

Along with the other cars, chassis number 1036 was eventually completed by faithful Tucker employees somewhat “off the record.” On October 18, 1950, this car, along with the other Tuckers built and all the other contents of the factory, went to auction at a sale conducted by Samuel L. Winternitz and Company, which took place on site at 7401 South Cicero Avenue. The car is believed to have been sold to the St. Louis area, where it was finally outfitted with a transmission and made roadworthy.

Around 1951, this car and a second Tucker were given to Ova Elijah Stephens, of Denver, Colorado. Stephens was known to the Denver public as “Smilin’ Charlie,” a nickname bestowed because the well-known underworld figure was never known to smile. He accepted the two Tuckers as down payments on the sale of the Silver Star Saloon, a watering hole and brothel in the small Centennial State town of Flippin, as is documented in surviving IRS records, copies of which are on file.

Smilin’ Charlie had no real use for the Tuckers, and chassis number 1036 was sold through Hugo Sills Motors, a Hudson dealer in the town of Littleton, to Rex McKelvy. In a lengthy interview for the August 12, 1988, issue of the Rocky Mountain News, McKelvy recalled the Tucker as “a fabulous car and good performer,” which had only 20 miles recorded when he purchased it!

With Preston Tucker’s downfall still fresh in the public’s consciousness, one of his cars was a “must” for the roadside antique automobile museums popping up all over America in the 1950s. Accordingly, when Denver businessman Arthur H. Christiansen opened his Colorado Car Museum at the foot of Lookout Mountain in 1958, he purchased Tucker number 1036 from McKelvy. Unfortunately, Christiansen’s museum lasted for only a year before its doors were shuttered and its cars were sold at auction.

Tucker number 1036 was acquired at the auction for $3,500 by Wayne McKinley, a successful Chevrolet dealer from O’Fallon, Illinois, and charter member of the Tucker Automobile Club of America. Mr. McKinley would be the Tucker’s longest-term owner, selling it after a quarter century in 1986 to Ken Behring’s Blackhawk Collection in Danville, California. In December 1989, the car was restored to its present appearance by Bob Holland’s Phaetons and Fins, of Menlo Park, California. A year later, it passed to Nobuyo Sawayama, of Osaka, Japan, for a figure widely reported as $500,000, which is believed to have been the highest price paid for a Tucker at the time.

In 1997, the Tucker was acquired by Bob Pond. For a decade, it remained as the centerpiece of his legendary collection, spending many years on prominent display, alongside his other most prized possessions, at the Palm Springs Air Museum.

The car is still wearing Mr. Holland’s restoration and is finished in an eye-catching shade of metallic bronze, which believed to be the 1966 Ford Emberglo. Its chrome and paint still have a nice shine, and the correct broadcloth interior shows only light wear; in fact, the broadcloth is believed to be the original material from 1948! Importantly, the car retains not only a proper Tucker Y-1 transmission—the gearbox that it was meant to have when new—but also the correct, proper late dashboard switchgear and Kaiser-sourced door handles. Only 1,914 miles are recorded, likely the actual mileage covered since new in the ownership of Smith, McKelvy, McKinley, Behring, and Pond.

To acquire one of the most legendary American cars is a rare opportunity. To acquire one with such well-known and utterly fascinating history is especially priceless. The saying remains as true today as in 1948: “Don’t Let a Tucker Pass You By.”

Special thanks to Mike Schutta.

| Monterey, California

| Monterey, California