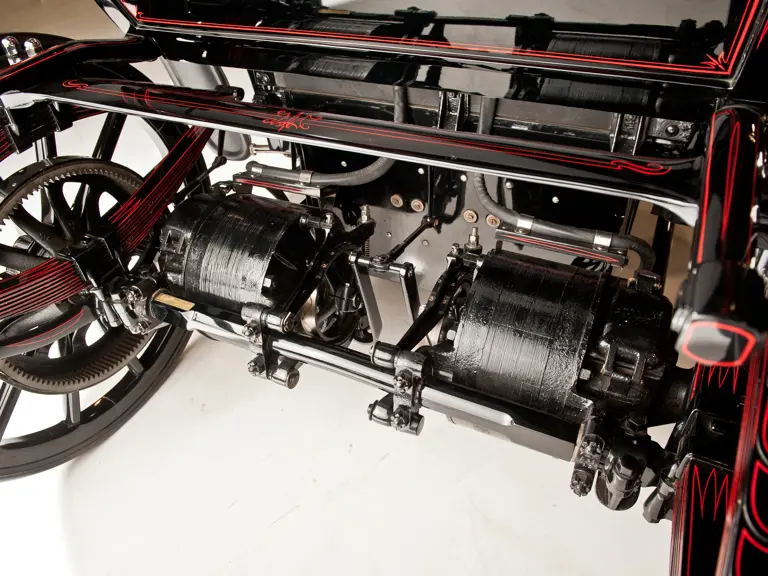

Mark XXXV. Dual direct-drive Edison DC motors, solid front and rear axles with full-elliptic leaf springs, and two-wheel mechanical brakes.

- Ex-James Cousens

- Elegant electric Landaulet

- Believed to be the only survivor

- Zero-emission horseless carriage!

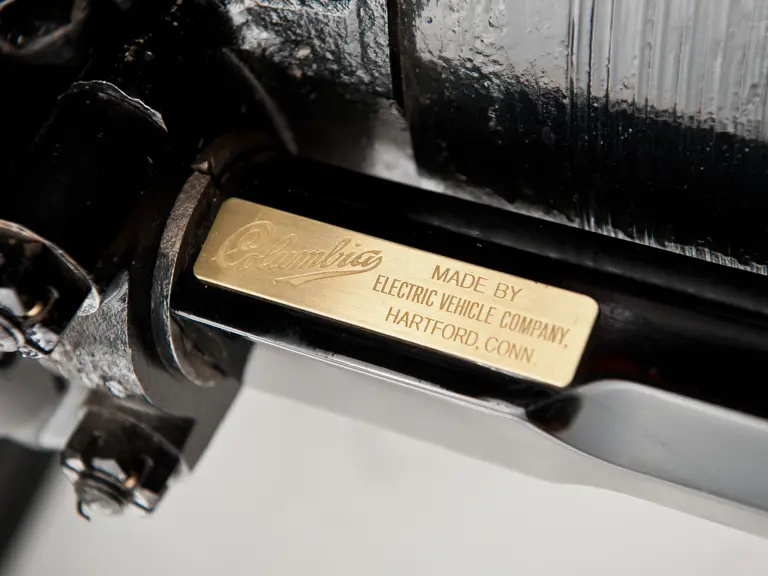

Colonel Albert Pope had become the nation’s largest bicycle manufacturer, and he aimed to do the same with cars. In 1896, he completed an experimental electric car and the next year hired Hiram Percy Maxim to head the motor carriage department of the Pope Manufacturing Company in Hartford, Connecticut. By 1899, they had built several hundred more electrics under the Columbia name, which he also used for his bicycles.

Meanwhile, the Electric Vehicle Company had been started by Isaac L. Rice in New York City, with the intention of building electric taxicabs. Rice had managed to put several dozen in service, which performed quite well during the city’s blizzard of 1899. Financier William Collins Whitney took notice and bought the company.

Whitney needed a manufacturing base, so he went to see Colonel Pope. The result was the Columbia Automobile Company of Hartford, organized in 1899. The Electric Vehicle Company was to be a holding company for a series of taxicab operating firms that Whitney wanted to create. Whitney, moreover, had grander ideas.

That same year, he purchased the rights to the Selden Patent, a very broad assemblage of claims that George B. Selden, a Rochester, New York patent attorney, hoped to use to collect royalties from the burgeoning number of manufacturers of gasoline motor vehicles. Whitney and Pope maneuvered the Electric Vehicle Company into a holding company and began issuing licenses to the likes of Buick, Cadillac and Oldsmobile. The income from the Selden licenses provided positive cash flow for Electric Vehicle, which soon took over from Columbia Automobile Company as manufacturer of Columbia cars, which were being built in both electric and gasoline form.

By 1902, there were nine models of Columbia electrics, carrying such names as “Mark XXXI Elberon Victoria” and “Mark XXX Seabright Runabout,” as well as a single Mark VIII gasoline runabout. In 1904, there were 22 separate electric models and three gasoline cars. Gradually the gasoline models surpassed the electrics in production, and the Selden Patent cash cow was slain by Henry Ford, the one “outlaw” manufacturer wealthy enough to take on the Electric Vehicle Company. In 1911 the patent was ruled valid, but it was found that existing gasoline manufacturers were not infringing, since no one used the type of engine on which Selden had based his “invention.” The company name had been changed again, to Columbia Motor Car Company, but its time was short. In 1910 it became part of Benjamin Briscoe’s United States Motor Company, a failed attempt to emulate General Motors. The Columbia car expired in 1913, by which time more than 27,000, both gasoline and electric, had been built.

Purchased from the James Cousens Cedar Crossing Collection in 2008, this Mark XXXV Columbia is believed to have been the sole example built with a three-position top. It is further believed but not documentable that following completion it was sent to Stevens Institute of Technology in Hoboken, New Jersey for testing and was then used in transit service in New York City, carrying officials and their guests.

Subsequent oral history holds that it was acquired by a wealthy plantation owner from Charleston, South Carolina, who had it transported south by train. After a few years of use, it was retired to storage, in large measure because of the difficulty in recharging. In the early part of the Twentieth Century, even major cities were not fully wired for electricity, and in rural areas it was all but unknown. This “infrastructure gap” hindered the popularity of the electric car prior to about 1912. Even after electricity became more readily available, improvements in starting and operation of gasoline cars rendered them more convenient to use for travel of any significant distance.

This Columbia was discovered in a Charleston carriage house in 1976. It was in need of restoration, which was subsequently carried out by Bruce Amster’s Hyannis Restorations in Massachusetts. The restoration was meticulous, and while it is now some years older, it has held up well. The body is painted gloss black, with extensive red moldings and striping matching the bright red leather interior. The running gear is black, with red striping on the springs and wheels. It runs on solid rubber tires. An imposing car, it is an extraordinary piece of engineering from the turn of the 20th century.

Please note that this car is offered on a Bill of Sale.

| Monterey, California

| Monterey, California