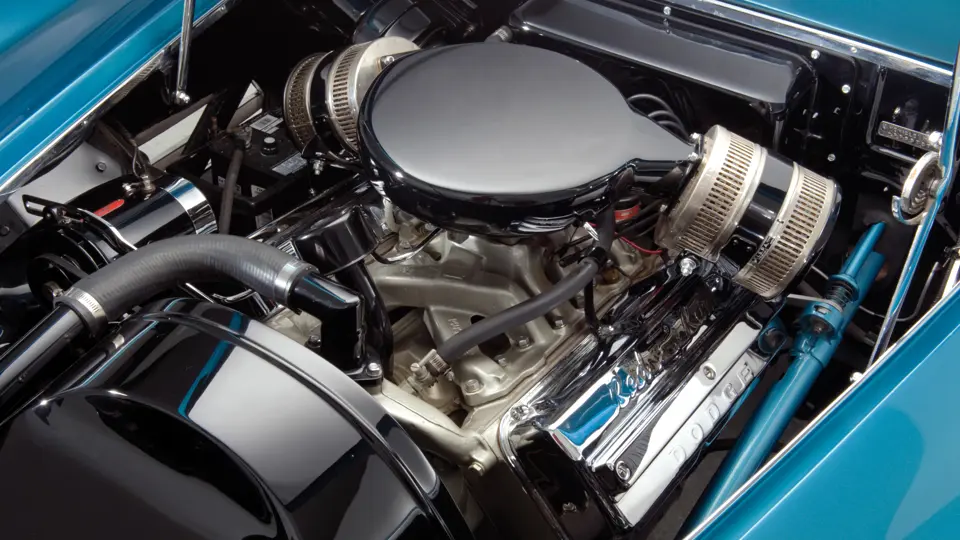

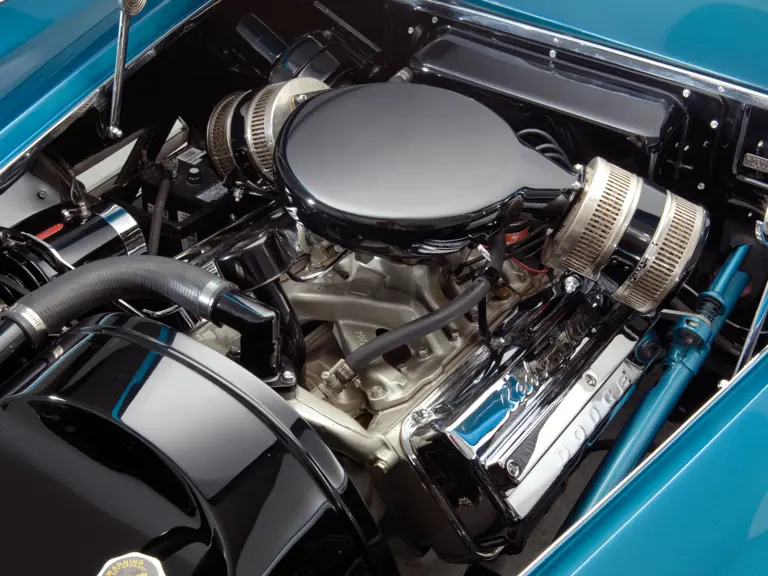

150 bhp, 241 cu. in. Hemi-head OHV V-8 engine, PowerFlite automatic transmission, independent front suspension with coil springs, live rear axle with semi-elliptic leaf springs, and Safe-Guard four-wheel hydraulic drum brakes. Wheelbase: 119"

- A Virgil Exner/Ghia masterpiece

- Restoration by Fran Roxas

- Driven to a closed-course speed record by Betty Skelton

During the early 1950s, such technological advances as air travel by jet, consumer electronics and rocketry captivated America’s imagination. Bringing a bit of outer space closer to earth were America’s burgeoning automakers, which created a succession of sensational dream cars. Of all such companies, though, Chrysler Corporation advanced the art and science of the concept car and carefully ensured that each of its respective divisions fielded their own variations on the theme.

In 1953, Dodge unveiled the Firearrow, a sleek, out-of-this-world roadster that provided a glimpse of what everyone’s new automobile would look like in just a few years. While it did indeed look like it was ready to drive the highways of tomorrow, it was just a rolling concept display model and had no running gear, unlike the majority of Chrysler’s other concept cars of the early 1950s. Public enthusiasm was strong enough that approval was given to design and build an actual running prototype, resulting in Firearrow II. Taking many styling cues from the first static model, this car also won acclaim fuelling speculation that a limited-production version would soon follow.

It was decided that further refinement was needed and that this car should be an aerodynamic masterpiece, a closed coupe with all the amenities needed for the modern driver. Since 1951, Chrysler worked closely with Turin, Italy’s venerable Ghia coachworks for its unparalleled expertise in producing eye-catching, “one-off” designs. Both the original Firearrow and the running second-series car were effectively designed and produced at Ghia, but Chrysler’s Chief of Advanced Design, Virgil Exner, was often credited with many of the corporation’s show-car designs and executions during this period. However, unlike some design leaders who insisted that they receive credit for everything produced under their direction, Exner believed that credit should be given to those who actually put pen to paper. That person, in the case of the Firearrow III project, was Ghia stylist Luigi Segre.

Having served with Ghia for several years, Segre was already instrumental in several earlier Chrysler projects, including the C200 roadster and the later K310 coupes. He established a working relationship with Exner as both men shared an appreciation of what these show cars should look like.

The visual impact of the new Dodge Firearrow III was impressive, a skilful combination of sheet metal, chrome, glass and paint, which represented a quantum leap forward in styling. Up front, its most notable feature was the smartly styled chrome grille fitted into a rectangular opening with concave vertical slats acting as air intakes. Four headlights, two standard hi-lo sealed-beam bulbs paired with smaller high-intensity driving lamps mounted to the outside, were placed in a recess on the centerline from which a defining trim line radiated, lending a most distinctive look. A pair of neat chrome bumperettes was mounted under the main lights, with two nearly concealed parking/turn signal lights mounted to the outer edges.

Peaked blade-like accents acted as a mid-level belt-line starting at the leading edges of the front fenders, wrapping around and continuing down the entire length of the body. A pair of handcrafted and functional chrome exhaust pipes produced an inspiring throaty rumble even at idle, with outlets routed through each rear quarter-panel. No detail was overlooked, with even the rear panel treated to custom touches including a broad, rearward-sloping trunk lid operated by a concealed pushbutton, while the taillights were carefully mounted into the trailing edges of the rear fins. Back-up lights were flush-mounted in the chrome-plated rear license plate holder, which was flanked by chrome bumperettes. Unlike European sports cars of the day, the wheel openings were flat towards the top, not the usual full-radius cutouts, while fashionable wide whitewall tires were mounted on chrome wire wheels with simulated “knock-off” centers.

Generous amounts of glass were utilized, starting with the steeply raked windshield, providing excellent visibility in concert with ample side glass and a large wrap-around backlight, which was one of the largest single pieces of glass used in any car up to that time.

Despite standing less than five feet high, the interior of the Firearrow III was quite spacious for the driver and passenger alike, starting with plush adjustable leather seats featuring Opal Blue bolsters and white leather inserts. The interior decor also reflected the car’s futuristic design theme with easy-to-operate controls within reach, and modern amenities including a fully functional heater-defroster system and top-of-the-line pushbutton radio. Heavy-pile carpeting padded the floor, and another important appointment was included – a large ashtray between the front seats.

As with the earlier Firearrow variants, this Series III coupe was mounted on a Dodge Royal regular-production chassis, the running gear and suspension was left stock, and the “Red Ram” mini-“Hemi” V-8 engine provided plenty of power, mated to the new, fully automatic PowerFlite transmission. Studies aimed at optimizing weight distribution resulted in handling far superior to the Firearrow III’s regular production stable-mates.

Once completed, the sleek blue coupe was earmarked to be the center of attention at the opening of Chrysler’s new Chelsea Proving Grounds in June 1954, at which point a daring young woman named Betty Skelton entered the picture. By the early 1950s, Miss Skelton had made quite a name for herself. Her first love was flying (she had flown solo at age 12 and by age 20 was considered one of the best aerobatic pilots in the world), and she had taken on a job as a charter pilot, often transporting racing drivers between events. She had also befriended NASCAR founder Bill France. He told her about the excitement surrounding Speed Week in Daytona and offered to locate a sponsor so she could attend. As a result, Betty Skelton was the talk of the beach and piloted a variety of Chrysler products to several records before being invited to take part in the opening of the Chelsea Proving Grounds.

Also invited were the top three drivers from the 1954 Indianapolis 500, and after being challenged by the men, Miss Skelton was given the privilege of driving Jack McGrath’s second place-winning racing car. However, the real reason she was there was to take the Firearrow III out on the new banked oval and open it all the way. She did, and in the process set a new world speed record for a woman on a closed course of 143.44 mph, while wearing a dress and high heels!

After Betty Skelton’s speed runs at the Chelsea Proving Grounds, Firearrow III was placed on the show circuit, becoming a crowd favorite and serving as the basis for Firearrow IV, an open-top variant. Soon after, the Series III and Series IV Firearrows provided Eugene Casaroll with the inspiration for his limited-production Dual-Ghia convertibles, which were offered in 1957 through Dodge dealers.

According to the prior owner of this exquisite car, once its show career ended, Chrysler arranged with U.S. Customs that in order to avoid paying hefty import duties due to its Italian coachwork by Ghia, the car would go back to its country of origin. Accordingly, in early 1955, Firearrow III was crated and shipped back to Ghia in Turin, Italy. From there, it was sold to a private individual in France, where it remained under the same ownership for the next 30-plus years.

During this period, the Firearrow III was maintained and, at first, used regularly. Later, it was driven and exhibited rather sparingly. Believed lost or, worse yet, destroyed, it was during the 1980s that an inquiry to an automotive magazine caught the attention of then-GM Chief of Design, the late Dave Holls. A letter to the editor from the owner of the car, still in Italy, was trying to locate some information about this unique coupe. Holls alerted a contact to the car’s whereabouts, and the pursuit to add this one-of-a-kind dream machine to a growing collection of similar historic concept cars began. After several months, contact was made with the owner, and then in short order, the Firearrow III was purchased and returned to the USA.

Next, Firearrow III received a “ground up” restoration by Fran Roxas, who returned the car to its original appearance. Finished in its original Opal Blue metallic paint with a color-coordinated interior of matching leathers, it looks just as it did when Betty Skelton was behind the wheel in mid-1954. Today, it stands proudly as an icon of when the American automotive industry led the world. While there are indeed a number of “dream cars” from the 1950s remaining in existence today, it is indeed rare to find a car such as this, which has been so painstakingly restored to its original configuration.

Of course, one of the most important aspects of the collector-car hobby is being able to own and preserve a part of history. The Firearrow III presents a most significant chapter as the only concept/dream car to ever set and hold a land-speed record, demonstrating that this beautiful blue coupe was not just built for show, but also for go!

| Monterey, California

| Monterey, California