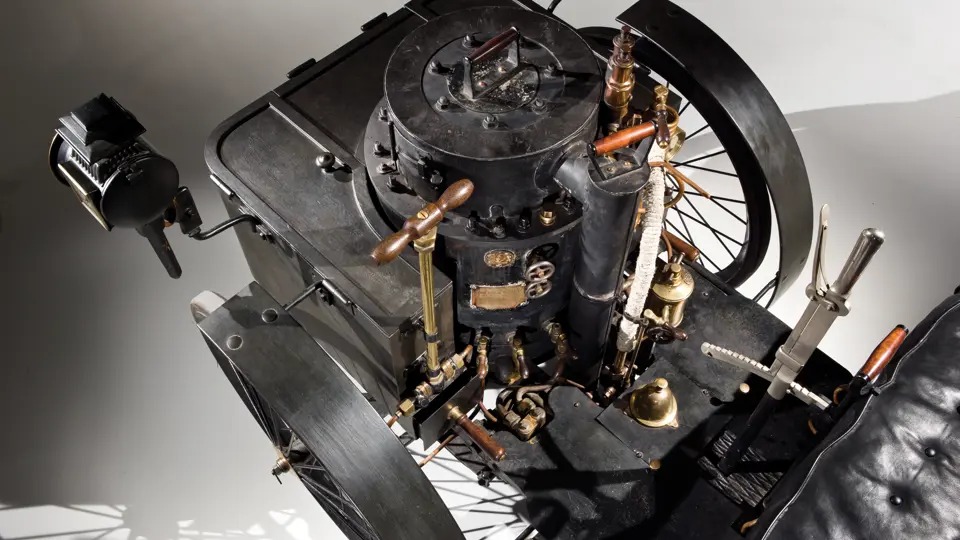

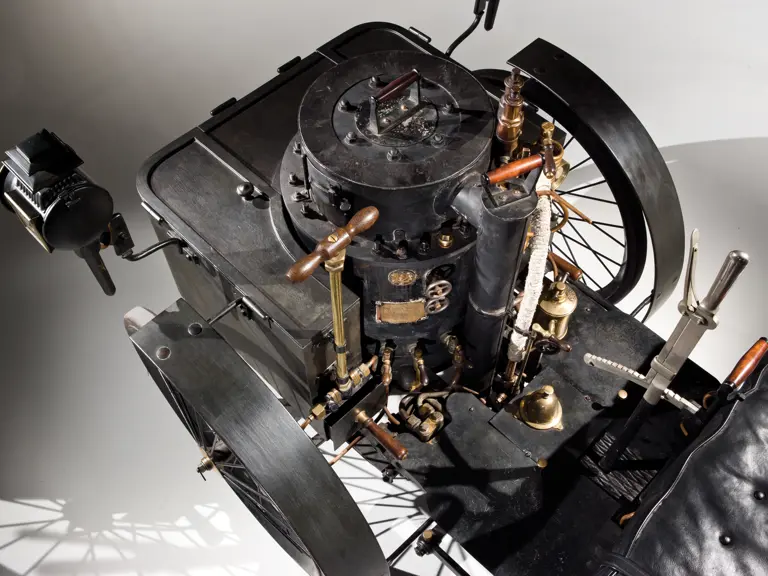

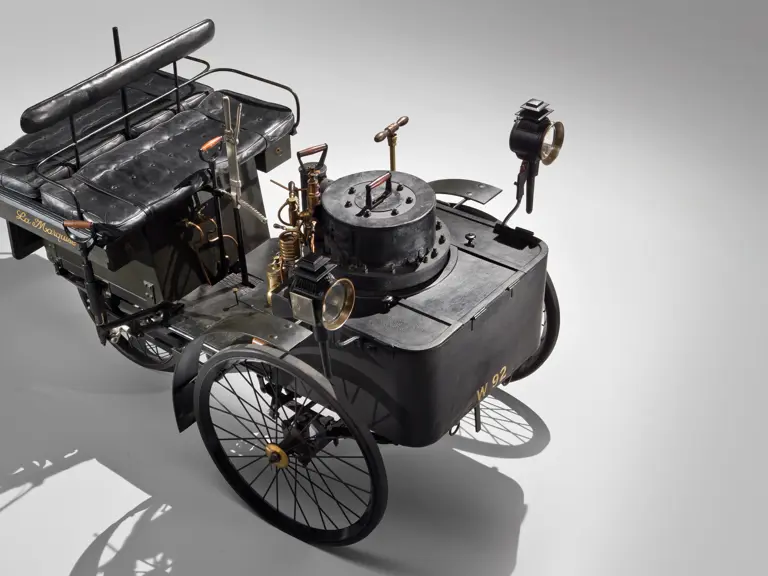

Twin compound steam engines, “spade handle” steering, solid front and rear axles with semi-elliptic springs, locomotive-style connecting rod motion, single-acting mechanical brakes. Wheelbase: 43"

- Named “La Marquise” after the Count de Dion’s mother

- At 127 years of age, the oldest running motor car in the world

- Single family ownership for 81 years and only four owners from new

- Participant in the first automobile race in 1887

- Veteran of four London-to-Brighton runs

- Pebble Beach Concours double award winner in 1997

- Capable of 38 mph, 20 miles on tank of water

- Veteran Car Club dating certificate #1750

- Offered from the Estate of John O’Quinn

When the young Comte de Dion stopped at the Giroux toy shop on Paris’s Boulevard des Italiens in December 1881, he was looking for toys to give as prizes at a ball he was planning. But he was intrigued by the quality of the workmanship of a model steam engine and asked who had built it.

Directed to the workshop out back, he found Georges Bouton and Charles-Armand Trepardoux. They were earning a measly seven francs a day building model boats and steam engines and scientific instruments. De Dion promptly offered them 10 francs a day and asked them to build a full-size engine, such as might power a carriage. So, in much the same way as the aristocratic Charles Rolls engaged engineer Henry Royce some 20 years later, a multi-class partnership was formed between a wealthy entrepreneur and working class craftsmen.

Bouton and Trepardoux set to work in a run-down building on the Rue Pergolese, near Avenue de la Grande Armee, the center of Paris’s bicycle industry, whose workers would soon be building automobiles. The problem with steam-powered vehicles was that efficient boilers were huge and powered locomotives and steamships. So how could one be miniaturized?

The two started off by adding a steam engine to a tricycle and then built a Victoria quadricycle in 1883. This had belt drive and inconvenient rear-wheel steering, and its liquid fuel was prone to suddenly catching fire. With its large vertical boiler up front, it looked like a coffee pot on wheels, so back to the drawing board they went. A year later, they came up with a much more practical arrangement, which is the car offered today.

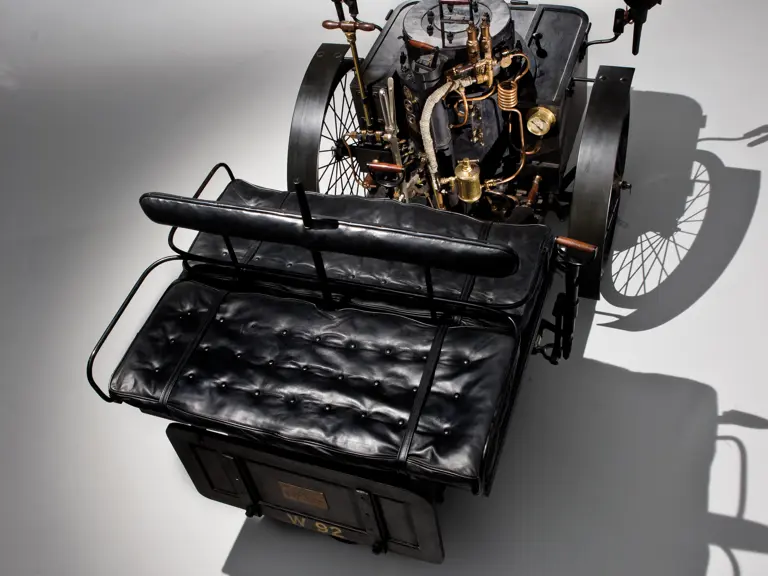

Dubbed “La Marquise,” after the Count de Dion’s mother, this quadricycle is much more compact, steering with its front wheels and driving the back wheels through connecting rods, rather like a locomotive. (The same principle was applied to the contemporary Hilderbrand & Wolfmuller motorcycle, though it proved difficult to ride, with so much unbalanced weight whizzing around.)

De Dion’s little quadricycle can claim to be the first family car, despite its arcane power source. What makes it different from road-going locomotives dating back to Cugnot’s 1770 tractor is its sophisticated boiler, which can be steamed in 45 minutes. It is also compact at only nine feet long and relatively light at 2,100 pounds. But, it has four wheels, seats four, and can be driven by one person – like a modern car.

Writer David Burgess-Wise examined “La Marquise” closely for Automobile Quarterly in 1995. He pointed out that it is both De Dion’s prototype quadricycle and the oldest running real car in private hands, so its credentials are unmatched.

“The only older functioning vehicle is the 1875 Grenville,” (basically a powered gun carriage), he said. “Amedee Bollee’s ‘L’Obesissant’ of 1872, now in the Conservatoire des Arts et Metiers in Paris, was working in 1923 and presumably could be got working again, but the museum doesn’t normally run its exhibits. There’s the chassis of the 1830 Gurney Drag in the Glasgow Museum, and the 1854 Bordino steam coach in the Turn museum is apparently complete, but neither is likely to run again.”

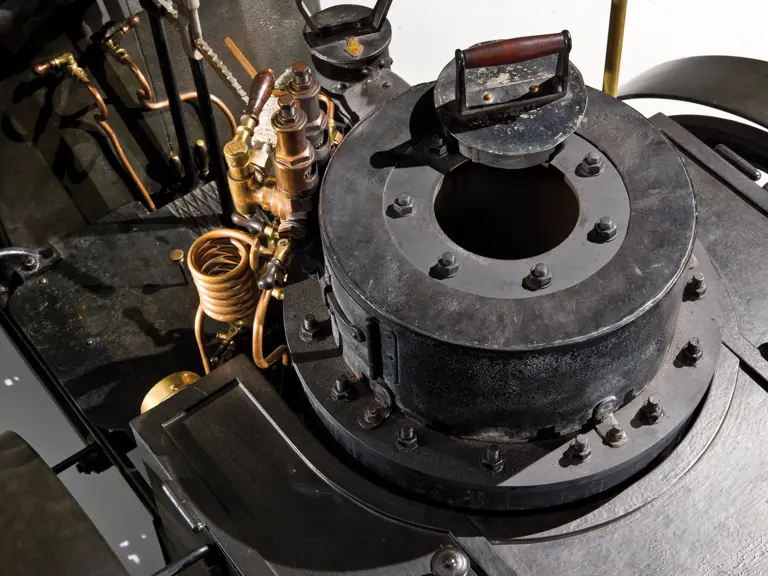

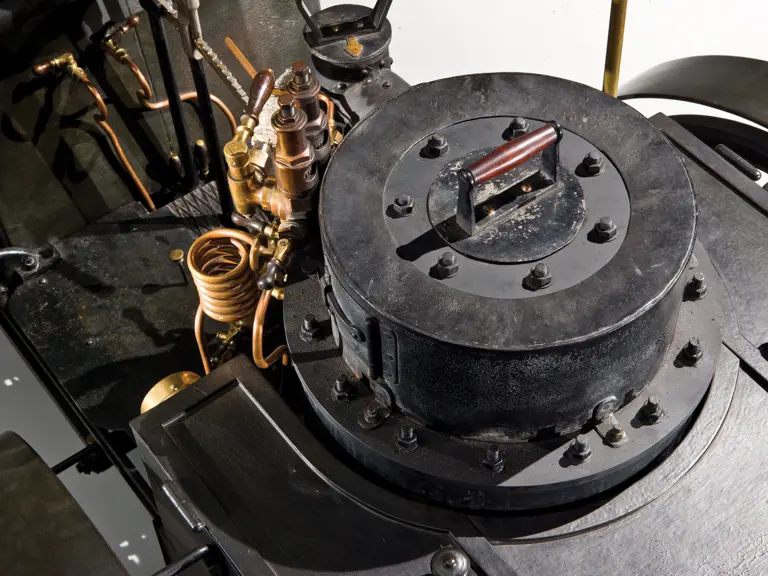

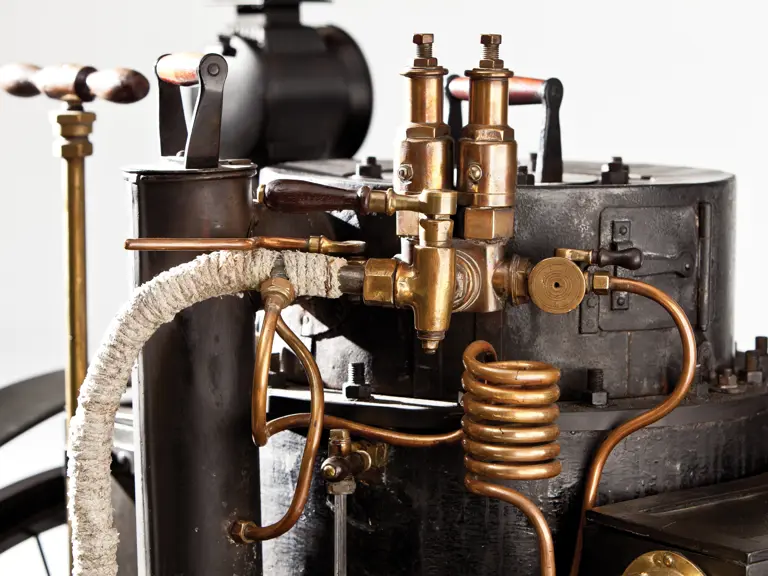

The mechanical breakthrough, which led to the building of La Marquise, was a new boiler design. The vertical boiler was much shorter and consisted of concentric rings, rather like Russian dolls. The two engines beneath the floor drove close-set back wheels via locomotive cranks. Water was carried in a tank under the seat, coke or coal in a square bunker surrounding the boiler. Coke was withdrawn via drawers at the bottom and poured down a pipe in the center of the boiler onto the fire beneath.

Driving “La Marquise,” Bouton participated in the first motor car race in 1887, (he was the only car to show up) averaging 16 mph for the 20 miles from Paris to Versailles and back and hitting 37 mph on the straights, according to an observer who timed him. The next year, De Dion in “La Marquise” beat Bouton on a three-wheeler, at an average of 18 mph.

De Dion produced sales brochures as early as 1886, with illustrations of a steam phaeton, dog-cart, truck, carriage and even an 18-seat bus (this when Benz and Daimler were still struggling with primitive three-wheelers). By 1889 you could buy a tricycle for 2,800 francs ($540) and a quadricycle for 4,400 francs ($850).

Those prices were certainly out of the reach for the average enthusiast, when a French laborer might make five francs a day, and sales were confined to the very rich. As a result, only about 30 De Dion steamers were made: 20 tricycles, four or five quadricycles, and a few larger carts and carriages, according to the world’s first automobile magazine La France Automobile in 1894. Two quadricycles remain and six tricycles are known, but none of those are operable.

By 1893 gasoline was the up-and-coming power source, and steam devotee Trepardoux left the firm and presumably went back to toys. A celebrated duelist and ladies’ man, De Dion was keen on animal welfare and made a few large steam trucks in an effort to free horses from hauling heavy carts, and then he and Bouton focused on gasoline automobiles. They patented their transmission in 1895 and dominated the early years of the 20th century, with De Dion engines powering some of the first great marques, like Renault, Pierce-Arrow and Delage. There were 88 De Dion Bouton cars in the London-to-Brighton Centennial run in 1996 – the largest single make.

“La Marquise” was built in De Dion’s new factory across the River Seine in the Rue de Pavillons at Puteaux, to which the company moved in 1884, when it outgrew its original premises. “We could employ as many men as we liked –12-15 and sometimes even 20,” boasted De Dion.

The new steamer seated four people in pairs and back-to-back “dos-a-dos” as it was known. The seats were located on top of the steel tank, which held 40 gallons of water, good for about 20 miles. The vertical boiler was ahead of the driver and surrounded by a bunker, which kept the fire fed with coal or coke through hoppers at the bottom, eliminating the need for stoking. A manual pump supplied water to the boiler initially, and when pressure was up to the operating level of 170 psi, donkey engines began working and water was supplied automatically.

Later in life De Dion declared that “La Marquise” “can be considered the embryo of the first touring automobile. It had four seats and it was already a family car.”

Count De Dion kept “La Marquise” until 1906, finally selling it to French army officer Henri Doriol. The Doriol family owned it for 81 years but never had it running, since it had lost brass and copper fittings to the war effort in 1914. Doriol displayed “La Marquise” at the Grand Exhibition at Grenoble, Switzerland in 1925 and was awarded a special Diplome d’Honneur.

Doriol and his son attempted to restore the quadricycle in later years but finally gave up and put it up for auction at a Poulain sale in Paris in 1987. Incomplete and non-running, it was bought by Tim Moore, a British Veteran Car Club Member. Another museum at Le Mans in France had an 1890 model, so Moore went to work copying the missing pieces on his car and had it running inside a year. Despite being a steam novice, he recreated the rear foot platform and wooden seat bottom, remanufactured brass fittings and pipes that had been sacrificed to the 1914 war effort, and re-tubed the boiler in 1993 at a cost of $20,000. He also replaced incorrect wooden, iron-tired wheels with correct spoked wheels and hard rubber tires.

The existence of the 1890 car, which differs in numerous details, enabled Moore to be absolutely certain that “La Marquise” was indeed De Dion’s prototype. Close examination of ancient photographs showed that one of the brackets holding the water tank to the frame had been extensively re-cut to clear a frame lug. Other unique features include the absence of “dumb irons” for the front springs; it’s the only car made with four-leaf springs all round and the only one with single acting brakes – the others all have extra brake pads at the rear. It also has unique sliding latches on the side vents on top of the boiler. More obvious evidence is the car’s original brass plate attached to the boiler, which records mandatory five-year boiler inspections in 1889, 1894 and 1899, after which it was probably retired.

After getting "La Marquise” back on the road, Moore campaigned her enthusiastically. He competed in four London-to-Brighton runs, at which he was always the first car away as the oldest entry, and successfully completed the trip at the 1996 Centennial, which attracted 661 of the 850 pre-1905 cars remaining in the world. Awards won by “La Marquise” include the 1991 UK National Steam Heritage Premier Award for Restoration and Preservation, a double award at Pebble Beach in 1997, winning the U1 steam class and the Automobile Quarterly Historian’s Trophy, class winner of Pre-Century Steam Cars at Goodwood in 1999, and honored at the 1996 Louis Vuitton Concours at the Royal Hurlingham Club in London in 1996.

Ironically, the last two times “La Marquise” has been sold, it was because owners Doriol and Moore each had two children and didn’t want to decide whom to leave it to. “I can’t cut it in half,” said Moore in 2007, “but it’s been a real wrench putting the papers together. I’m a very reluctant seller.”

With impeccable provenance, fully documented history, and the certainty that this is the oldest running family car in the world, “La Marquise” represents an unrepeatable opportunity for the most discriminating collector. It is unquestionably and quite simply one of the most important motor cars in the world.

| Hershey, Pennsylvania

| Hershey, Pennsylvania