Outstanding restoration of a very rare car, which tucks its wheels underneath for storage.

SPECIFICATIONS

Manufacturer: Robert Hannoyer

Origin: Levallois-Perret, Paris, France

Production: est. 17

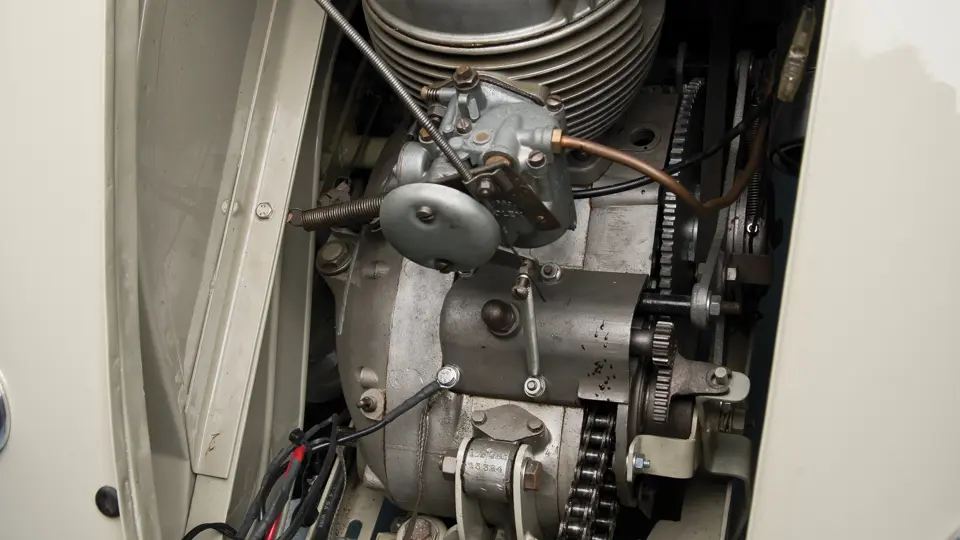

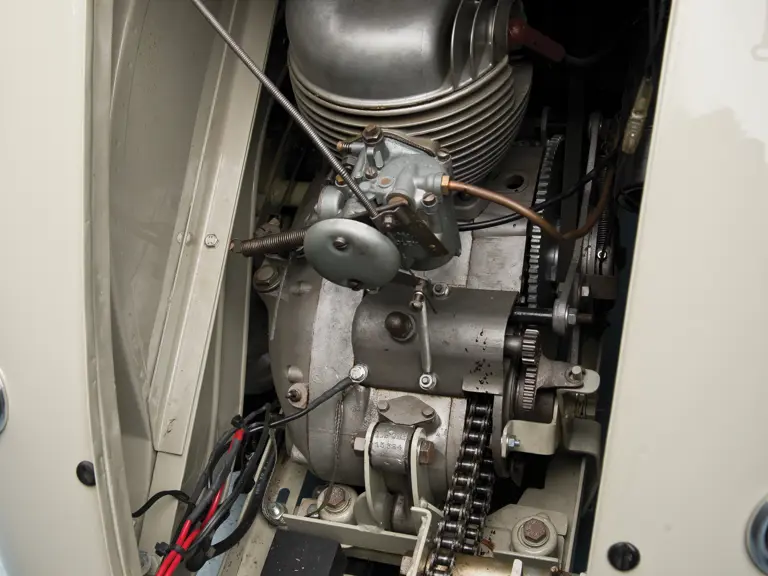

Motor: A.M.C. 1-cyl, 4-stroke

Displacement: 175 cc

Power: 8.5 hp

Length: 9 ft. 6 in.

Identification No. 1706

The post-war economic climate in France was one of shortages and restrictions. The cyclecar, with its fiscal advantages, was treated quite seriously, and a number of entrepreneurs (some inspired, others less so) entered this competitive field. One such entrant was “garagiste” Robert Hannoyer, proprietor of a large, successful auto repair shop in Paris. The startling vehicle he displayed at the Paris Salon of 1950, named Reyonnah for the reversed spelling of his name, was an exceptionally original conception that owed nothing to existing designs (the Messerschmitt and Inter three-wheeler tandems were both three years in the future).

One of the post-war restrictions was on public parking space. In answer to this, the Reyonnah’s most ingenious feature was its ability to fold up its front wheels under the car in order to reduce its width and be able to be moved off the street through a garden gate, courtyard doorway, or even into a house. This was made possible with the front suspension’s parallelogram arms and flexible hydraulic brake hoses. The car’s nose was easily lifted due to its light weight, and the wheels collapsed together on their own accord to a width of only 29 inches. There was no lock to hold them in the “garage” position when the car was rolled forward.

The prototype car on the stand at the 1950 show differed somewhat from the production models. Its sleek body shell, built by Jean Demarne, featured fully enclosed rear wheel “fender skirts” and elegant helmet-style front fenders, as well as a belt line that curved down and back from the folding chrome-plated windshield and up at the curved tail. The front seat was of the exposed-tube aircraft type. The car had unique radially-slotted wheels. There was no evidence of a top at the show, but the same car was photographed later with a sideways-tilting canopy incorporating a canvas top.

The production version of the car that emerged in the spring of 1951 looked slightly different, with its high, straight beltline, cutaway rear fenders, and simpler motorcycle front fenders. The windshield was now fixed and body-colored, and the car had a pair of narrow running boards, with aluminum footpads on the right side, for “leg up” access to the interior. The aircraft-style lifting canopy was hinged on the left and could be had with either a folding canvas top or a slightly taller steel hardtop incorporating side windows and a sunroof. The wheels of the pre-production car still owned today by the Hannoyer family have circular perforations and feature elaborate, colorful paintwork. Production cars used the solid disc wheels from the Simca Cinq. The interior was improved, and the large steering wheel was extended under the dashboard into the hinged front luggage compartment. There was a choice of motors by AMC or Ydral, at first with hand-starting via a long bar and later with an electric start.

Hannoyer was determined to make a splash in the press by entering his car in two ACF-sponsored events. In 1951, he entered the Paris-Chartres economy run, and in 1952, he built a special “Torpedo-Sports” model for a speed run at the Montlhéry race track. The Torpedo, which featured a low, streamlined windshield and tonneau cover, hit 100 km/h in a high-speed run, a notable achievement at the time for a 175-cubic centimeter car.

Despite five Paris Show appearances, press coverage, and full order books, which even gained an offer of production from a coachbuilding firm, actual production capital was not forthcoming in the end, and the determined entrepreneur closed his doors in 1954. This exceptionally rare car originated from France and was painstakingly restored by the museum to the condition seen today.

| Madison, Georgia

| Madison, Georgia