1924 Hispano-Suiza H6C "Tulipwood" Torpedo by Nieuport-Astra

{{lr.item.text}}

$9,245,000 USD | Sold

Offered from Masterworks of Design

{{bidding.lot.reserveStatusFormatted}}

- Inarguably the most famous Hispano-Suiza in the world

- Commissioned by aperitif heir and gentleman racer André Dubonnet

- Raced by Dubonnet in the 1924 Targa Florio and Coppa Florio, finishing 6th and 5th overall, respectively

- Stunning lightweight mahogany coachwork, a masterpiece of craftsmanship

- Part of several famed private collections over nearly a century

- The subject of artwork and models; featured in every book on the marque

- Extensively researched by marque historian Hans Veenenbos

ANDRÉ DUBONNET’S ‘TULIPWOOD’ TORPEDO

Aperitif scion André Dubonnet lived a life of excitement—six aerial victories as a young pilot during the Great War, development of a namesake automotive suspension he sold to General Motors, and a pioneer of solar energy. In between all these things he competed in Olympic bobsledding and loved fine, swift automobiles, racing Bugattis and Hispano-Suizas. It was the latter that would make his name immortal in motoring circles; he would commission a particularly fabulous streamlined coupe on an H6C chassis from Saoutchik, and create his own Hispano-Suiza-powered automobile, which failed to fledge. Both of these came after his most famous Hispano-Suiza, a car now known to enthusiasts as the “Tulipwood” Torpedo—a car that has been famous since virtually the moment of its birth.

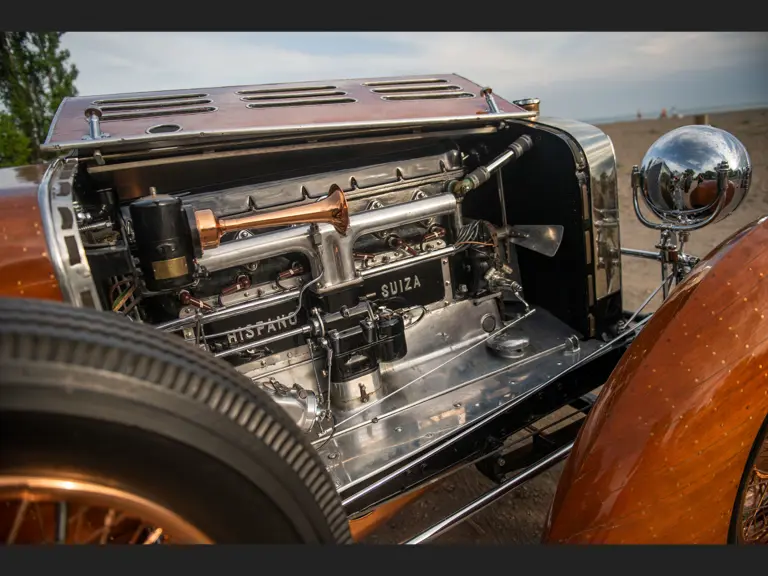

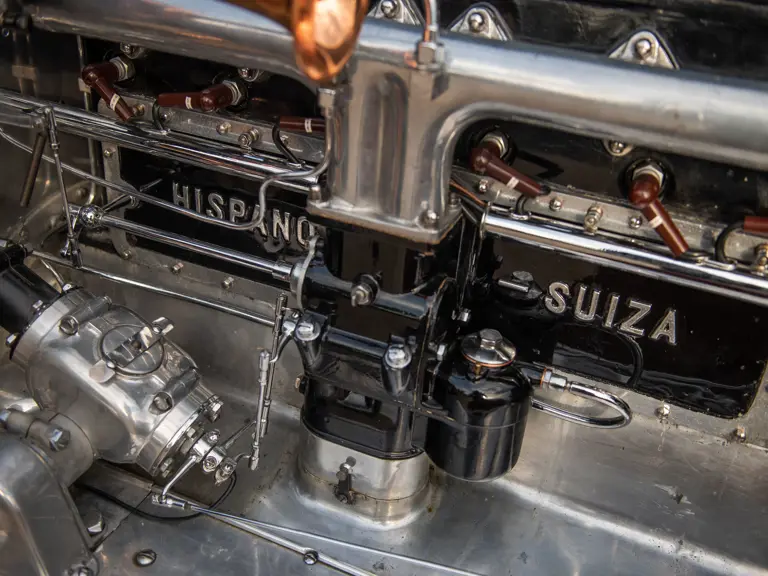

Dubonnet’s machine began as an 8-liter overhead-cam Hispano-Suiza H6C chassis of the newly developed Type Sport. Only Hispano-Suiza co-founder Marc Birkigt himself took delivery of an H6C earlier, reflecting the aperitif heir’s importance to the firm. Dubonnet’s was one of three factory-built lowered surbaissé chassis, fitted with a lowered radiator and a 52-imperial gallon fuel tank, a necessity for long rallies. That the frame was originally surbaissé is seen in a surviving photograph of the engine compartment when new, depicting the lower angle of the water hoses between the top of the cylinder block and the radiator, as well as by comparison of period photographs with other, standard H6C chassis.

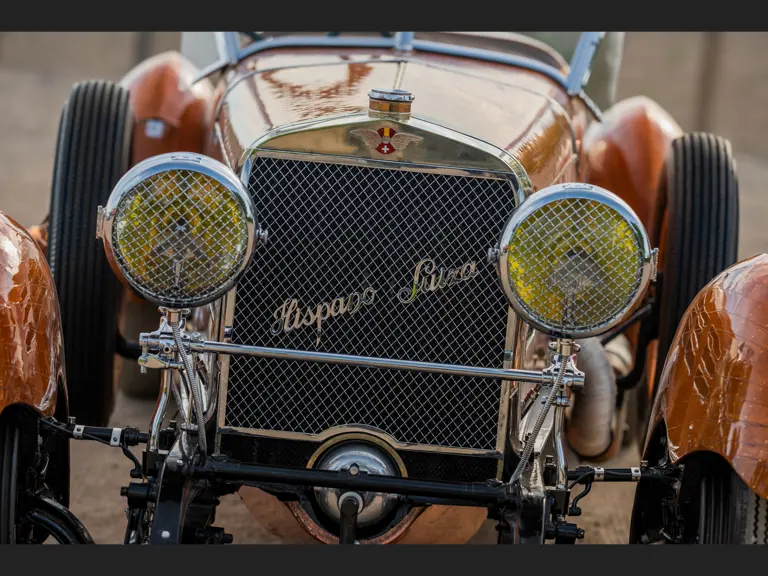

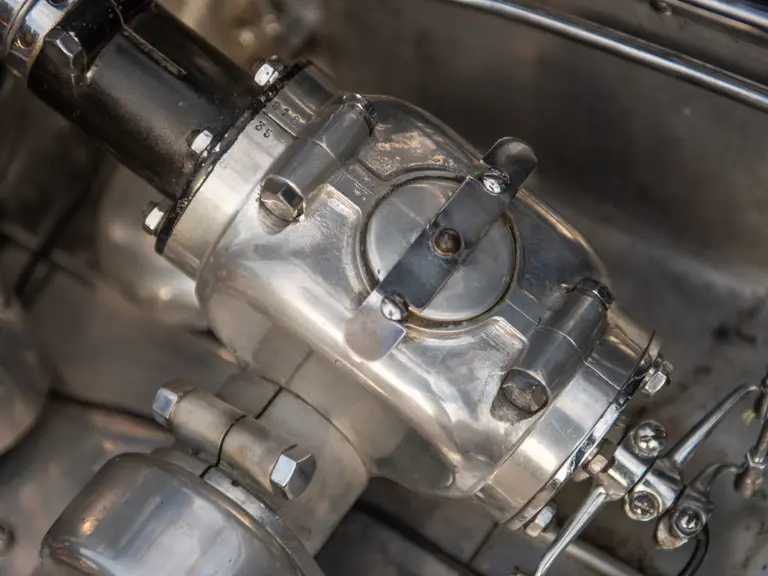

The true brilliance came in the coachwork. Some of Dubonnet’s competitors, many of themselves aviators, had begun to figure out that aircraft construction methods could yield techniques useful in the construction of lightweight bodies; thus emerged the earliest fabric-bodied coachwork of the period. Dubonnet seemed to cut out the drawing board between aviation and automobile, commissioning aircraft manufacturer Nieuport-Astra of Argenteuil to body his car. Their creation was designed by their engineer Henri Chasseriaux and formed of delicate 1/8-inch-thick strips of mahogany—not actually tulip wood, but romantic legends and alliterative names both die hard—formed over an external layer that was in turn laid over inner 3/4-inch ribs, all secured together by many thousands of aluminum rivets and varnished. Similar to the “skiff” bodies pioneered in the Teens and Twenties most notably by French coachbuilder Labourdette, Nieuport’s torpedo reportedly weighed only 160 pounds, featherweight by the standards of bodywork to be fitted to such a large automobile; by comparison, it added virtually nothing to the weight of its chassis and engine.

On 27 April 1924, Dubonnet drove the H6C, fitted with Paris registration 6966-I6, in the Targa Florio through the torturous Sicilian mountains, widely considered one of the most rigorous and dangerous performance tests of the era, and finished 6th overall. He then ran the additional lap to complete the Coppa Florio, running 8 1/2 hours on the Madonie circuit, to finish 5th overall, despite his appalling luck with tires. Both events demonstrated the practical success of Hispano-Suiza’s engineering and Nieuport-Astra’s innovation; Dubonnet’s driving skill and the fascinating wooden coachwork made a heavy brute—reportedly the largest car on the field—into a true competitor.

It is not exaggeration to state that the Tulipwood Torpedo was as advanced and remarkable a performance automobile in 1924 as the Pagani or McLaren are held to be today; both employed their time’s most potent drivetrains and state-of-the-art lightweight materials to ensure maximum performance, with no regard to cost. The results were breathtaking in every regard.

THE MOST FAMOUS HISPANO-SUIZA IN THE WORLD

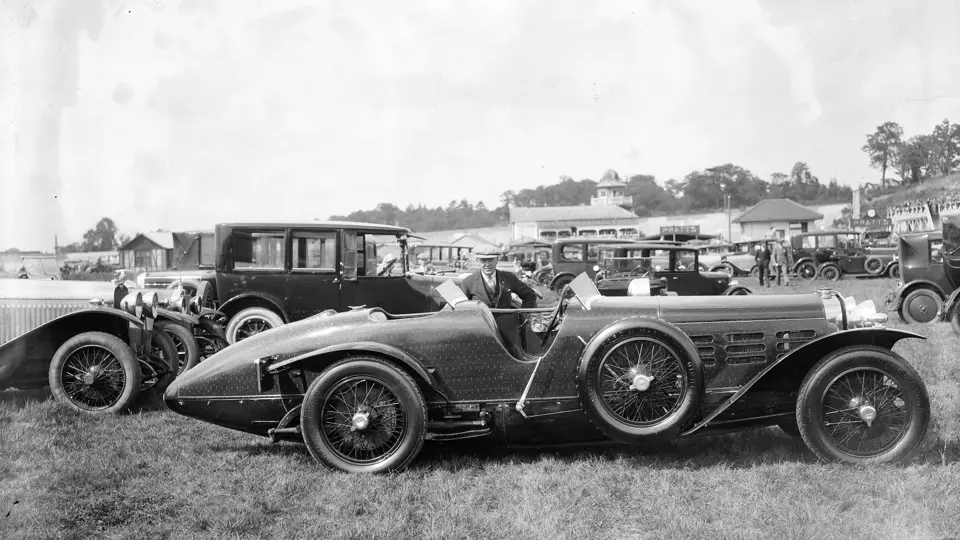

Subsequent to its brief but successful competition career, Dubonnet equipped his car for road use, with flat open fenders, a low windscreen, a small door and a large searchlight added on the passenger’s side, headlights, etc., as shown in a photograph taken of him with the H6C. Subsequently the Hispano-Suiza was briefly owned by a Coty, believed to have been the noted Hispanophile Roland Coty, the perfume magnate’s son. According to the biography A Zest for Life, marmalade heir, archaeologist, and automobilist Alexander Keiller from Scotland acquired the car from Coty in early 1925. It was registered by him in London as XX 3883 soon thereafter.

During Keiller’s ownership the car was photographed in the parking field at Brooklands. Additional photographs from his ownership show that the car now had a cover over the rear seat; tendril-like flowing wings, later replaced with cycle-style fenders, and other minor trim changes, as well as what appears to be a new exhaust system. The flowing open fenders and other touches were likely added for Keiller by coachbuilder Barker, whose name appears on original photographs of the car in the Nethercutt Collection’s library; they are very similar to those on Barker-bodied Mercedes-Benzes and Rolls-Royces of the era.

Keiller eventually put the Hispano-Suiza away in the storage facilities of a coachbuilder, possibly Hooper, in Plymouth, and there it remained through the duration of World War II. According to the late, great British motoring historian Bill Boddy in his article “White Elephantitis,” published in the September 1959 issue of Motor Sport, while in storage “a bomb splinter caused some damage to the tail but otherwise it remained in original trim.”

In 1950, Rodney Forestier-Walker discovered the car in storage, and after tea with Mr. Keiller, succeeded in its acquisition. After covering the war wounds in the tail with plywood, modifying front and rear windscreens, and replacing the original Blériot headlights with Lucidus lights, he kept and drove the Hispano-Suiza for six years, writing fondly of his travels in it in an article, “A Journey to Remember,” published in the 3 March 1954 edition of The Motor.

Gerald Albertini, a Standard Oil heir and passionate automobile enthusiast living in London, spotted the car at roadside in 1955, and in the age-old fashion left a note on the windshield offering to buy it. Six months passed before a change in Forestier-Walker’s circumstances led to the consummation of the transaction, held at an appointed spot on a Welsh roadside, as the seller’s family was heartbroken and did not want to see the car go. The return trip home necessitated a pause for fuel, at which Mr. Albertini sat down for a leisurely cup of tea, emerged, and found the attendant still laboriously hand-pumping vast quantities of fuel into the tail’s 52-gallon tank! To add insult to injury, the wealthy owner found his wallet empty, and was forced to pawn his watch to pay for the fuel.

Albertini soon undertook a restoration of his new acquisition, with the mechanical components rebuilt under the supervision of the great Hispano-Suiza technician, George Briand; reportedly the car had only a little over 17,000 miles and showed virtually no wear aside from the clutch. To suit Mr. Albertini’s build, a smaller steering wheel was mounted and the seat moved back, necessitating fitment of a longer outside cranked gear-lever.

Coachwork restoration was handled by Panelcraft of Putney, with repairs made to the areas damaged in the war using new wood, numerous trim changes including copper plating throughout, and the interior outfitted in cream leather. The cycle-style fenders fitted by Mr. Keiller were replaced by the elegant wooden torpedoes currently mounted. Each was meticulously hand-crafted by an elderly boat-builder, Harry Day, who assured Mr. Albertini that “if a craftsman can make them in metal, be assured I can make them in wood.” Each fender was formed of a hand-beaten alloy shell, over which was laid a skin of polished wood, steamed to fit and secured by matching aluminum rivets, then sanded perfectly smooth and polished. The result was fenders that appeared not as an afterthought but to have been there all along, and they still do to this day.

At its completion by Panelcraft, the restored Hispano-Suiza was taken by Mr. and Mrs. Albertini on an extended tour of France and Italy; a photograph taken in 1957, published on the cover of the German magazine Auto Motor und Sport, shows it with luggage mounted for the tour!

In 1964 the Hispano-Suiza made its way stateside courtesy of renowned Bentley collector E. Ann Klein. It was rapidly acquired by Richard E. “Jerry” Riegel, Jr., a longstanding enthusiast, motoring historian, and much-missed friend of many, with a letter in the file from Panelcraft describing to him work completed in Mr. Albertini’s care. In Mr. Riegel’s ownership the Hispano-Suiza was occasionally shown with pride during the 1960s. It appeared in the annual Sports Cars on Review exhibit at the Henry Ford Museum in 1965, and four years later at the New York Auto Show.

The Hispano-Suiza was bought from Mr. Riegel at Kirk F. White’s 1973 Philadelphia auction by the late John Warth, who, his son Richard fondly recalls, collected it thereafter and drove it from Pennsylvania into New York City to dine at Lutèce with the restaurant’s owner, fellow French coachwork partisan André Surmain. According to Richard Warth, his father subsequently sold the car to Anthony Bamford, later styled Lord Bamford, then again brokered its sale to wealthy racing driver Michel Poberejsky, also known by the nom de course “Mike Sparken,” who registered it in France in Hauts de Seine as 2396 EA 92. From Poberejsky the car is believed to have passed in 1982 to a Greek shipping executive, Ares Emmanuel, living in London. Around this time, it was also the basis for one of Gerald Wingrove’s elaborately detailed models.

In 1983, the car was acquired from Emmanuel by a new owner, and beginning in late 1985 subsequently underwent an eight-month restoration by Mike Fennel. It was debuted at the completion of the restoration at the 1986 Pebble Beach Concours d’Elegance, winning the Alec Ulmann Trophy for Most Significant Hispano-Suiza. Several years later, it was purchased for the present collection, where, aside from very occasional museum display, it has remained since—preserved and largely out of sight, but seldom out of mind of passionate collectors. During this time, it has continued to occasionally be featured in books and magazines, most recently in November 2021 in the heavily detailed edition of the Hispano Drivers Club Newsletter No. 16, by its editor/publisher Hans Veenenbos.

Overall, the “fuselage” body remains largely in preservation condition. It retains its original woodwork, including the inner sub-layers of wood that shape the outer curves, as noted by recent inspection by RM Auto Restorations. RM notes that some portions have been patched over the years, likely correction of the aforementioned shrapnel damage, with early repairs with aluminum and wood, those done by Panelcraft, and later repairs using some fiberglass. Whereas the car exhibits some age from storage, as well as several fender and metal trim modifications made at Albertini’s behest by Panelcraft, it still makes an impressive statement. At the time of the latest restoration the body was refinished with an orange stain and an outer clearcoat, rather than the original furniture-type varnish. This gave the body rivets a brass tint, but they are actually all aluminum as original. The number “6096” was found marked in chalk on the back of the front seat. Accompanying the car is a fascinating history file, including photographs and research compiled by the noted Hispano-Suiza historian, Hans Veenenbos.

The “Tulipwood” Torpedo is, to borrow an apt cliche, the stuff that enthusiast dreams are made of. Admired and desired its entire life, it is inarguably the best-known Hispano-Suiza, and among the most famous French automobiles ever built—a car held along the Bugatti Atlantic and “teardrop” Talbot-Lagos, a pantheon of small and select company.

| Monterey, California

| Monterey, California