| Los Angeles, California

| Los Angeles, California

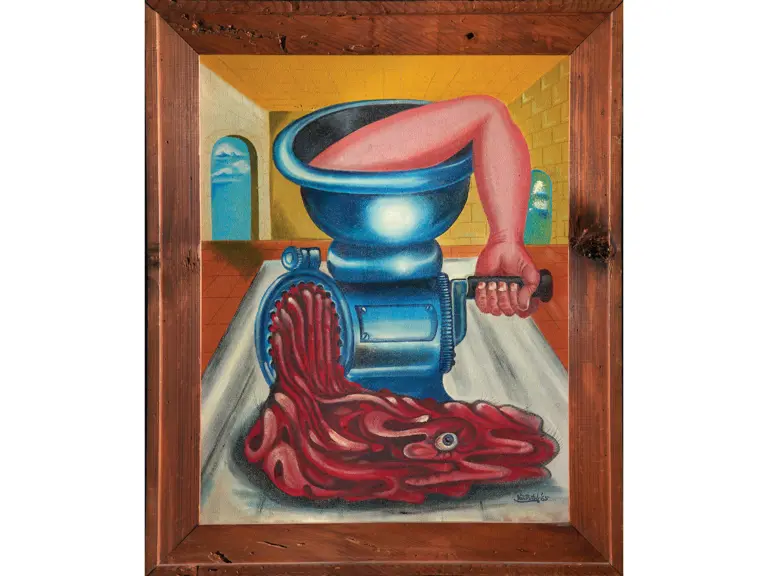

Von Dutch

Oil on canvas

Signed and dated lower right

1965

24 × 20 in., framed

Considered one of his most recognizable works, Good-Bye Cruel World is claimed to be Dutch's second "self-portrait." The piece features a meat grinder in the foreground processing what appears to be a human body. A hand protrudes from the top of the grinder and turns the crank. It should be noted that despite the fact that the body has been ground into raw meat, a single eyeball has gone through the grinder unscathed and remains intact staring out at the viewer. This is significant for a multitude of reasons.

The flying eyeball was Dutch's self-proclaimed signature and calling card, and in the years to come was almost as recognizable as Dutch himself. The significance of the remaining eye is highly indicative of Dutch's personal thoughts on the Third Eye and enlightenment concepts, known also as the Sixth Chakra, or sometimes even as remote viewing. Belief in this concept varies across the board, but one can infer that the soul and subconscious can live on despite the body's demise, whether serene or violent, as pictured in Good-Bye Cruel World.

Without question, one of Dutch's favorite artists was Salvador Dali. By the 1940s Dali was considered the ultimate surrealist. At a time when artists such as Dali, Pablo Picasso, and Jackson Pollack were featuring their strange new art forms, Dutch was doing so as well. Practicing artists were trying to break away from conventional painting, and it is not hard to see how Dutch's imagery fit into all of this. It is thought that his infamous flying eyeball was in homage to Dali, as it is reminiscent of the eyes in an Alfred Hitchcock movie where Dali painted the dream scene. The exaggerated perspective seen in Good-Bye Cruel World is very characteristic of Dutch's later paintings. The cruel and dramatic subject matter is not new and is once again a commentary on social behavior in the world at the time.

Dutch's popularity began in the late 1950s; his pinstriping was legendary, and people sought out his work from everywhere; meanwhile, stories of his outlandish behavior were beginning to grow daily. Dutch found this personally troubling, as he did not want to be known as a personality; however, his seclusion and introspective personality only fueled more rumors. He became a man trapped in a myth. Dutch became trapped within this persona and thought he could not grow artistically without diverging from it. The painting can be often viewed as a commentary on this matter with the underlying concept being that the largest weakness a person can have is his or her self.

Jimmy Brucker, on the other hand, saw this painting as a premonition. In the last years, hard living and drinking caught up to Dutch. Dutch loathed doctors and hated hospitals, and though he was in a great deal of pain in the final years of his life, he continued to remain reticent and resistant of professional medical assistance. By the end of his life, Dutch had quit drinking, but it was too late and the damage was already done. Brucker asserts the painting was illustrative of Dutch's inner feelings. Dutch was indeed his own worst enemy and inevitably destroyed himself, whether through his excessive lifestyle or instability.

Exhibition History: Laguna Art Museum, Laguna Beach (17 July–7 November 1993); Maryland Institute College of Art, Baltimore (3 December–23 January 1994); Center on Contemporary Art, Seattle (29 May–17 July 1994).