Est. 120 bhp, 298.6 cu. in. overhead camshaft inline eight-cylinder engine, three-speed manual transmission, solid front axle and live rear axle with semi-elliptic leaf springs, and four-wheel hydraulic drum brakes. Wheelbase: 131"

• Rare bespoke Corsica coupe with interesting dorsal fin coachwork

• Legendary Stutz Vertical Eight

• Optional high-compression engine

Stutz was advertised as the “car that made good in a day.” The day was May 30, 1911, when a car designed by Harry Clayton Stutz competed in the inaugural Indianapolis 500. It did not win—that honor went to Ray Harroun in a Marmon—but its 11th-place finish, for a car completed just days before the race, was sufficiently remarkable to launch production of the Stutz Model A and one of the world’s most memorable automobile slogans. Most notorious among early Stutz cars was the Bearcat speedster model, and a racing team, called the “White Squadron,” held sway with specially-designed overhead cam four-valve engines from 1915 to 1917.

After a period of corporate instability and the departure of Harry Stutz, the Stutz Motor Car Company came under the direction of Hungarian-born engineer Fredrick Moskovics. Moskovics completely redesigned the Stutz car, with a new six-cylinder overhead cam engine, a double-drop chassis frame and worm gear rear axle, safety glass and four-wheel hydraulic brakes. The latter feature was noteworthy for its design. Termed “hydrostatic,” the system used water with an anti-freeze additive, but for one year only. Although somewhat boxy in comparison to competitors, the Stutz rode several inches lower. “The Safety Stutz,” it was called, with the “Vertical Eight” engine. These terms would be used for the remainder of the company’s life.

Stutz returned to racing with the Vertical Eight, the first competition being the Stevens Challenge Trophy race of 1927 for closed-body production cars. A steel-bodied Stutz sedan clocked an average of 68.44 mph for 24 hours at the Indianapolis Motor Speedway to win the Stevens Trophy. The Stutz Black Hawk, a two-passenger aluminum-bodied speedster later added to the catalogue, was the AAA Stock Car champion of 1927, winning every race in which it was entered. Stutz is perhaps best-remembered, though, for the race it didn’t win. At a particularly boisterous gathering of wealthy car enthusiasts, Moskovics made a $25,000 bet with his friend Charles Weymann, inventor of the Weymann fabric body construction for which Stutz held the American rights. The wager turned on the results of a match race to be run between Moskovics’ Black Hawk and a Hispano-Suiza, odds-on favorite due to its three-liter advantage in displacement. Run at Indianapolis three days prior to the Stevens Challenge, the contest was to be a 24-hour ordeal, and Moskovics counted on his car’s greater agility and acceleration to carry the day. They didn’t. After 56 laps, the Stutz swallowed a valve, giving the race up to the Hispano. Weymann was impressed with the Stutz performance, however, so much so that he entered one at Le Mans the following year.

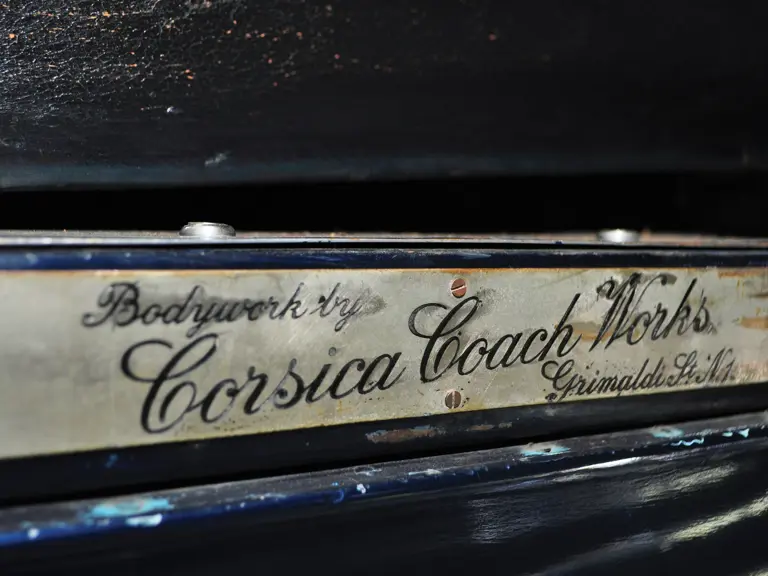

This car began life as a Black Hawk speedster. Bodied by Millspaugh & Irish, the Indianapolis coachbuilders best known for work on Model A Duesenbergs, on a right-hand drive chassis, it was purchased by the owner of an Australian winery. Some time thereafter, and most likely in period, it was re-bodied into the current distinctive two-passenger coupe by British coachbuilder Corsica of London.

Corsica Coachworks was established at Kings Cross, London in 1920 by Charles Stammers and his brothers-in-law Joseph and Robert Lee. Never large, the firm claimed not to have employed designers, preferring instead to directly carry out its customers’ devices and desires. Because Corsica was small and could cater intimately to customers’ whims, the workshop attracted many of the sporting crowd, and while little is known of the early ’20s Corsica output, a good deal of it is believed to have involved Bentley.

The early 1930s brought some of the best-known Corsica coachwork, including a low-slung sports body for the Double Twelve Daimler and an open two-seater for Donald Healey’s 1935 Triumph Dolomite, by which time the works had moved to Cricklewood. Other Corsica clients commissioned work on Rolls-Royce, Alfa Romeo, Mercedes-Benz and Bugatti chassis. Like many of the bespoke builders, Corsica closed its doors during World War II, never to re-open.

The car’s second owner used it to promote his popular circus in Australia. It came to the United States in the 1950s and was repainted in the current blue over the original black. Otherwise it is an amazing original car, unmolested since the period re-body into the intriguing dorsal-fin coupe. It was recently re-commissioned for the road, with new tires and a complete service of the fuel and braking systems.

| Phoenix, Arizona

| Phoenix, Arizona