Among the rarest and most spectacular early competition cars ever built, the 1908 Mercedes 17.3-Liter 150 HP 'Brookland' Semmering Rennwagen represents a true Holy Grail moment for collectors.

A brief but pivotal era in motorsports history gave birth to some of the most exhilarating and legendary automobiles ever created. This period, characterized by unrestricted displacement and groundbreaking innovations, propelled motorcars to an unparalleled level of performance that remained unchallenged for decades. No other epoch in motorsports history featured such massive power plants at the pinnacle of competition. This peak, which lasted from 1904 to 1908, was exclusively reserved for racing and never intended for public road use and the few surviving examples of these cars have become highly sought-after artifacts in the annals of motoring history. During this era, Mercedes dominated the technical landscape, occupying a virtually unchallenged position of superiority.

The Mercedes, which was introduced in 1901 by Daimler Motoren Gesellschaft, quickly established its reputation as the finest car of its time. The masterwork of Wilhelm Maybach and Paul Daimler’s design team, the Mercedes built upon earlier designs of Gottlieb Daimler, Paul Daimler, and Panhard et Levassor.

The Daimler motorcars that existed before 1902 were still heavily based on Gottlieb Daimler’s pioneering designs of the 1880s. With intake valves of the atmospheric type, opened by suction, and engines regulated by a governor keeping them at a constant 800 rpm, the operator had little control over the engine besides selecting gears. Ignition was either by hot tube or mechanical make-and-brake, again with no control by the operator, while chassis were quite high with unusual transaxles and chain drive. These Cannstatt Daimler cars were high-quality and expensive machines, but by 1901 were heavily outclassed by the products of France.

Enter Emil Jellinek, a DMG sales agent and motoring enthusiast. He felt Daimler was not producing cars as modern as the competition and challenged engineers to design something “Not for tomorrow but for the day after tomorrow.” To tempt Maybach engineers to design this superior car for him, he offered a prize of 550,000 DM.

Maybach delivered on the challenge, producing the groundbreaking product we now know as a Mercedes. To avoid conflicts with licensing of the Daimler name throughout Europe DMG needed a different name for this product, so Jellinek’s daughter Mercedes became the namesake.

Wilhelm Maybach’s innovations included large, mechanically operated intake valves, a refined spray-jet carburetor with throttle and automatic mixture control, and a flexible, driver-controlled engine, replacing the mechanical governor. The Mercedes/Bosch make-and-brake ignition system provided full control over ignition timing while engine displacement was significantly increased, with more aggressive camshaft timing resulting in a responsive and powerful motor far surpassing anything Gottlieb had envisioned.

The Mercedes was promptly fitted into a chassis heavily influenced by the Panhard et Levassor and Paul Daimler’s light car design but now featuring longer and lower pressed C-channel steel frame members. A remarkable transaxle with four-forward speeds and a groundbreaking H-pattern shift quadrant completed the package. These innovations produced the first truly modern high-performance automobile.

The 35 hp version, initially the highest performer, was followed by the legendary 60 hp. Despite its introduction in 1902, few cars could match its stellar performance even a decade later.

Daimler knew racing success sold cars so he was determined to dominate the highest level of competition, and its new Mercedes racing cars quickly showed their capability against their established rivals. The 60 horsepower race cars claimed prominent victories in the Coupe Gordon Bennett and the Vanderbilt Cup in America. However, a devastating fire soon destroyed the factory fleet of rennwagens. In a daring move, Daimler borrowed previously sold customer 60 hp cars to compete in the upcoming grands prix.

Despite the success of the 60 horsepower, Daimler faced significant challenges in creating a superior successor. The much anticipated 90 horsepower model failed to meet expectations, while a short-lived six-cylinder racing model, despite its impressive 120 horsepower, also proved to be a flop. Recognizing the importance of returning to the foundation that had made the 60 horsepower such a landmark, Mercedes decided to revert to its roots.

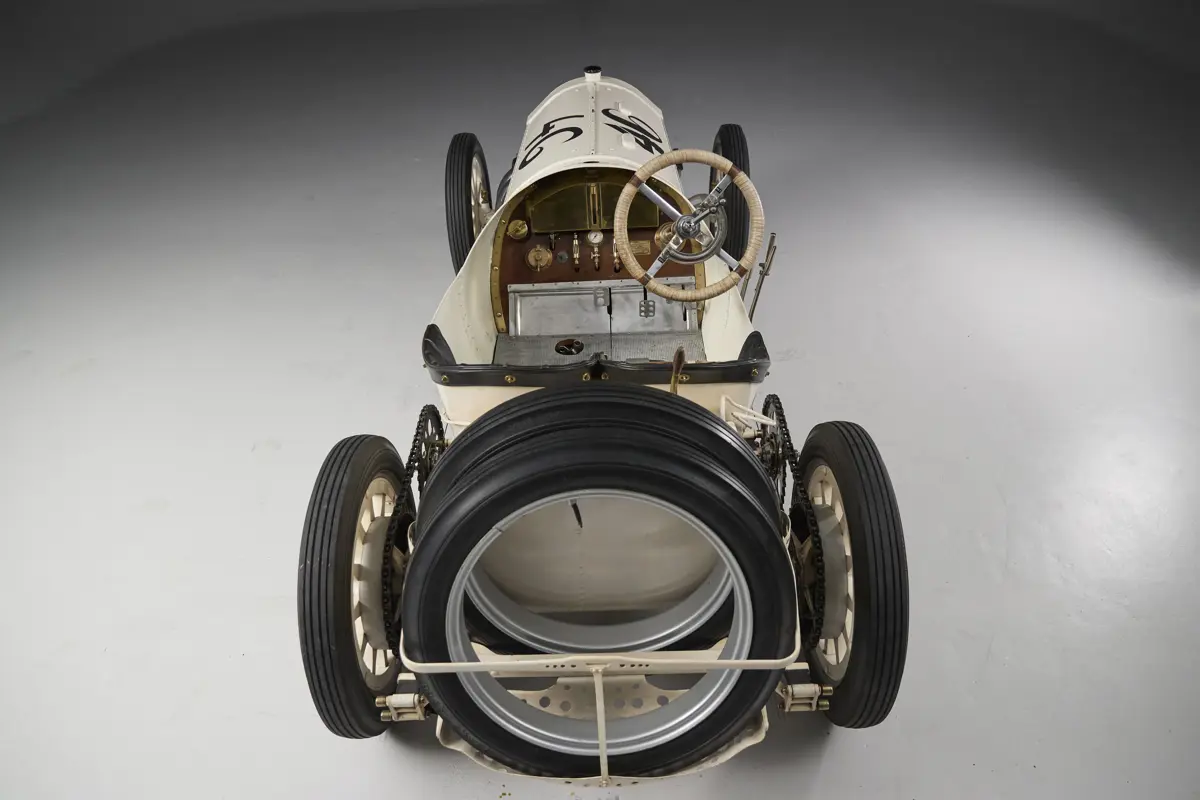

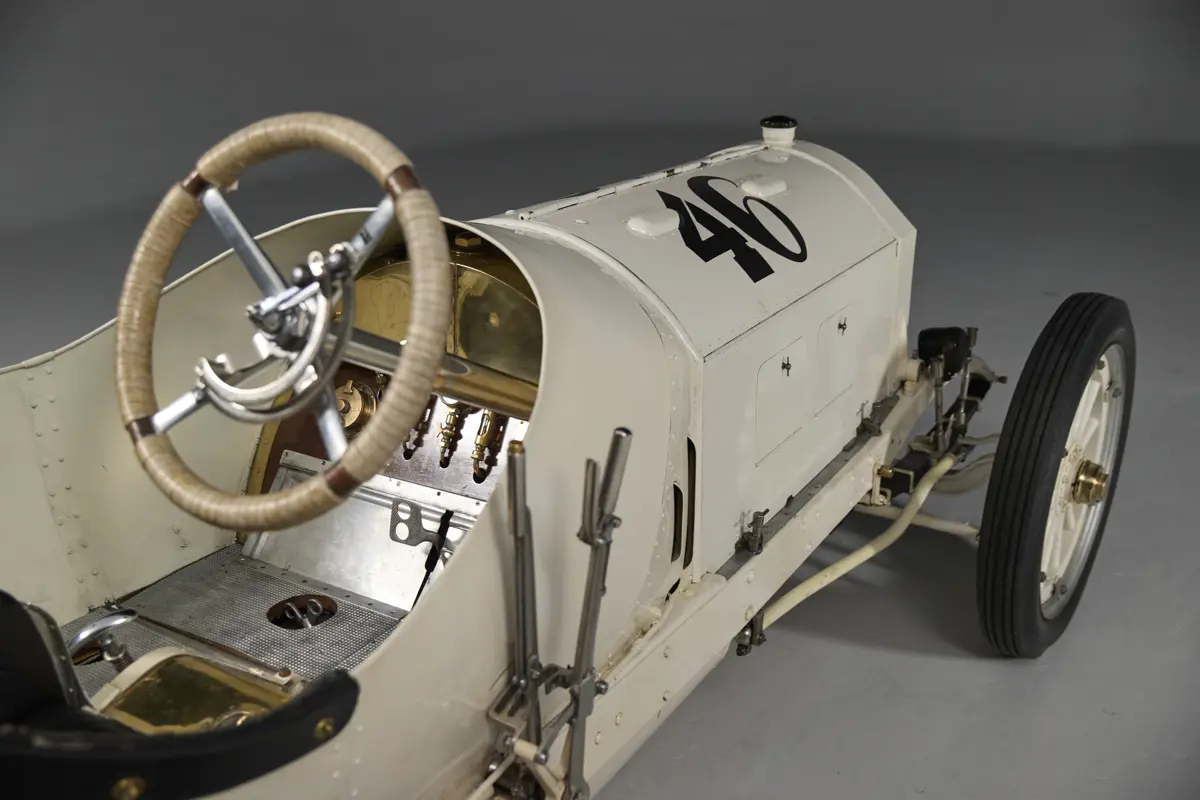

In 1907, Mercedes showcased its technical expertise once more by assembling a comprehensive racing package that dominated the competition. Their focus was on optimizing their core technology and crafting a meticulously designed complex package. Refinements and enhancements of the classic Mercedes engine resulted in a potent and reliable series of engines ranging from 80 to 120 horsepower. The chassis was meticulously engineered to lower the center of gravity, utilizing drop section frame rails to lower the engine further within the chassis. A unique driving position was adopted, placing the driver in a long and low stance, positioning their weight near the rear axle. By employing the transaxle design, the transmission, differential, and dual braking systems were integrated midships, significantly reducing unsprung weight, while two transaxle-based brake systems were conveniently adjustable through floor-mounted adjusters.

The most striking innovation was the fully enveloping coachwork that provided protection for both driver and mechanic. This exceptional bodywork stands as a high point in the racing car aesthetics of its era. Despite the immense power of the engines, Mercedes designers ensured that the cars remained compact, particularly in the front end. The relatively small radiator and hood were a result of the low engine placement and substantial weight reduction from an area that was deemed unnecessary.

All these innovations resulted in a car that stood out starkly from its contemporaries, sitting low to the ground and appearing significantly lighter than its rivals. Reduced weight translated into improved acceleration, longer tire life, and enhanced braking and handling. While some competitors prioritized engine development, Mercedes, having mastered engine technology, allocated their efforts to the rest of the car.

The new Mercedes racing cars would be termed ‘Brookland’ type and would prove a return to form for DMG. A decisive victory by Lautenschlager at the 1908 French Grand Prix showed German prowess in a country that had dominated the automobile industry for years.

Winning Grands Prix was important, but the Semmering hill climb in Austria was a top priority for Mercedes in 1908. This technically demanding event showcased the cars’ superiority in a meeting that demanded raw power, exceptional handling, and brakes that could withstand rigorous use. The course up the Semmering Pass consisted of a series of tight switchbacks ascending the steep mountain. Mercedes drivers famously stated that winning the Semmering was achieved in the corners.

Mercedes took the Semmering hill climb event so seriously that they commissioned a specially built car for the occasion. The Semmering car, commissioned on 16 July 1908, featured a Brookland Grand Prix-type chassis with modifications tailored for the Semmering terrain.

For 1908, a specially enlarged version of the 120 horsepower engine was constructed. The four-cylinder Mercedes engine now boasted cylinders with a bore of 6.9 inches and a stroke of 7.1 inches, resulting in a displacement of nearly 1,100 cubic inches or 17.3 liters. Rated at 150 horsepower, this engine represented the most powerful and largest Mercedes engine ever built, as well as the most potent iteration of the original Mercedes engine design. The groundbreaking engine was equipped with a specially designed Mercedes carburetor, featured Mercedes make and brake ignition, and incorporated a high-tension magneto.

The new Semmering Mercedes, equipped with front fenders and road equipment, was designed to be driven directly from the German factory to Austria for the hill climb. Mercedes team GP driver Otto Salzer personally piloted the car to the event, ultimately securing a decisive victory, surpassing his teammate in second place. This triumph established a new course record, showcasing the success of Mercedes’ efforts in developing the special car.

Unwilling to rest on its laurels, Mercedes recognized the need for a more robust engine to cope with the prodigious output of its current design. For the 1909 event, Mercedes developed a unique and hardier engine of the same displacement; it’s remarkable to think of a manufacturer in that era constructing a one-off engine for a single event.

Mercedes’ efforts were once again rewarded as the new engine, coupled with further lightened chassis configuration, propelled Salzer to victory once again. His time of 7 minutes and 7 seconds shattered his previous course record, standing for an impressive 15 years.

To put the performance of the 17.3-liter Semmering car into perspective, consider the results in 1926 when Rudolf Caracciola tackled the legendary climb in a supercharged Mercedes K racing car. Despite being a class-winning 6.2-liter Porsche-designed K Rennwagen, it completed the same course nearly a minute slower than its predecessor from 1909!

The Semmering Mercedes would race one more time for the factory, this time driven by the “Red Devil” Camille Jenatzy in the unlimited displacement race in Belgium. From there Daimler sent the car to London, where it was purchased by wealthy Australian sportsman Lebbeus Hordern. It passed through the hands of a few other Australians and notably made an appearance at an event marking the introduction of the new Mercedes 300. Held on an Australian racing circuit, the nearly 50-year-old Mercedes humbled the technological marvel of the 300 with its superior performance.

I’m not certain if any other car in history can make such a claim.

During its time in Australia the Mercedes was always looked after and raced in numerous events. It stayed complete and intact until being acquired by American David Gray, a pioneering West Coast collector and one of the largest heirs to the Ford Motorcar Company fortune who had some fantastic cars in his time. Tony Hulman became aware of the treasure Gray possessed and set about trying to acquire it. After parting with the unheard-of sum of $30,000 in 1962, Hulman acquired the Mercedes for the Indianapolis Motor Speedway Hall of Fame Museum.

Mercedes has had periods of complete domination at motor racing’s highest level, with the Silver Arrows of the 1930s, the W 196s of the 1950s, and even the Hamilton era of Formula 1. But this early Mercedes period, perhaps its most dominant and impactful, was marked by the fewest surviving cars. The few that remain stand as the last remnants of an incredible period of innovation, performance, and success.

Experiencing a Mercedes racing car from this era is not only rare, but truly special. The brutal power of a 17.3-liter engine in a car of such unparalleled quality and sophistication creates an experience that many—including myself—consider among the greatest on four wheels.