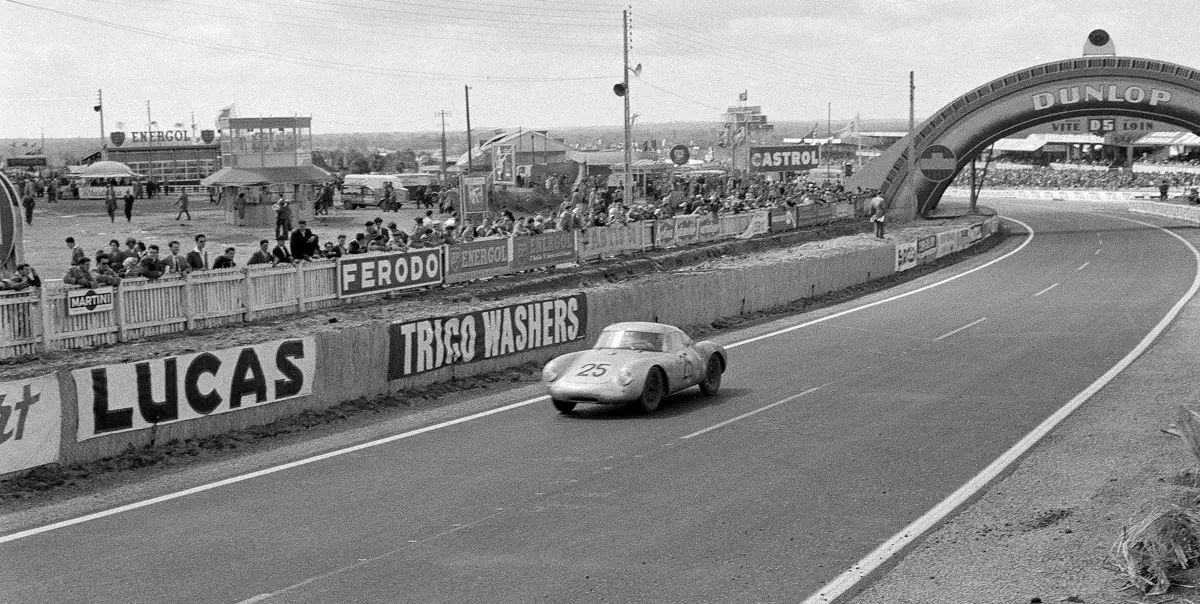

Behind the wheel of a museum-grade Porsche 550A ‘Le Mans’ Coupe.

It started in a workshop in Stuttgart—the quest to win Le Mans. Not content with class wins, by 1956, Porsche decided to push their engineers to compete against the top contenders. With their four-cam ‘Carrera’ engine limited to 1.5 liters, fighting against Ferrari and Jaguar could only be won by efficiency and handling; a David-vs-Goliath-style battle. Porsche would have to out-engineer their opponents. Fortunately, engineering was a Stuttgart specialty.

A roof may seem like a minor addition, or even an afterthought, in an endurance race like Le Mans, but not for a detail-focused manufacturer like Porsche. Motorsport has always served as a very critical part of the evolution of Porsche, an experimental laboratory for the engineering of new products. Getting behind the wheel of a museum-grade artifact like this 1956 Porsche 550A Prototype 'Le Mans' Werks Coupe is a window into the past.

Made for the Mulsanne Straight, the removable roof on the 550A Prototype was made for high-speed stability, meant to channel air to the two intakes between the rear fenders. Designed by Austrian aerodynamicist Erwin Komenda, who also created the sculpted forms of the Volkswagen Type 60 and proposed V-16 Auto Union Type 52 supercar, as well as Wilhelm Hild, the organic shape of the 550A prototype seems to have originated by theoretical intuition. Certainly, Porsche did not have their own wind tunnel in the 1950s—their engineers’ innate abilities self-evident.

Take, for instance, the driver’s door on the 550A Coupe. Notice the top of the frame extends into the roof panel, allowing the pilot easier access during fast-paced, running Le Mans-style starts. Ford’s GT40 also featured a cut-out door—eight years after this Porsche raced. Also worthy of note is the door handle, a metal ring which pulls on the interior door handle, an ingenious solution that both saved weight and scarcely impacted the overall drag.

Inside, even casual observers could perceive the weight-saving regime. A utilitarian cabin was common for Porsche racers; so-called “speed holes” can be seen dotting the handbrake and shifter brace. The windows were crafted from lightweight Plexiglas, which allowed them to be ventilated. At the official weigh-in before the Le Mans race, the sprightly Porsche totaled a scant 595 kilograms. This slim curb weight allowed for maximum maneuverability and acceleration.

A veritable workshop for budding drivers to build their reputations, Richard von Frankenberg and Wolfgang Graf Berghe von Trips were chosen to pilot this Werks Prototype during Le Mans. Still regarded as the ultimate endurance challenge, von Frankenberg and von Trips were cocooned inside a tube frame chassis, constructed to be both stiffer as well as lighter than their previous effort, the 1953 Porsche 550 Coupe, which can be viewed in detail on the Revs Institute website. The Porsche method of constant improvement paid dividends.

The massive effort in engineering refinement created one of the most iconic Porsche racing cars of all time. Ken Miles, reviewing the 550A in Sports Car Graphic, concluded, “The sum total of the various modifications was an improvement in handling that was almost unbelievable. Gone was the excessive oversteer. The RS was now about as forgiving a car as one could possibly wish to meet.” Miles’ positive assessment was proven at Le Mans, with this chassis, 550A-0104, battling through incessant rainstorms and brutal three-way competition between Jaguar, Aston Martin, and Ferrari. In the face of such challenges, only thirteen cars completed the race with a classified finish.

Focused on running a clean race, the 550A Coupe of von Trips and von Frankenberg outlasted its inter-company competition. The other 550A chassis, no. 0101 of Umberto Maglioli and Hans Hermann suffered engine failure after completing 136 laps over sixteen hours, a heartbreaking result which opened the door to this chassis, 550A-0104. Winning the under 1.5-litre class outright and finishing in a respectable fifth place overall, this Werks Prototype Coupe raced into the record books, solidifying the legacy of Porsche. Perhaps more impressively, this chassis finished 37 laps ahead of its nearest class rival, a privateer Maserati 150S.

After dawn arrived at Le Mans and the checkered flag fell, this Werks Prototype not only proved out the intuition of its talented designers and engineers, von Trips and Von Frankenberg’s victory validated an entire company. Porsche placed second on Le Mans Index of Performance, averaging a blistering speed of 98.19 mph. This little coupe was a fearsome competitor, a “Werk-shop” serving as inspiration for generations to come.