When we look back at the storied nameplates of old coachbuilders, it is easy to assume that legendary brands have always been that way. Before they were trim levels or model designations, way before most were acquired by OEMs in an attempt to boost image, coachbuilders were independent entities, artists-for-hire. For the hundred or so we know of, there was an equal number of aspirants who maybe only worked on a chassis or two before fading away. Then, as now, it is hard to convince someone else to pay you to customize their car when you haven’t done it before, especially when the chassis in question is as fine as a Pierce-Arrow.

This was the situation in which Tom Hibbard and Ray Dietrich found themselves. Both were born in the 1890s, in Brooklyn and the Bronx, respectively, and both were working creatively from a very early age. Dietrich, age twelve, got an apprenticeship at the American Bank Note Co. in Manhattan and learned the intricate engraving process involved in crafting the plates that print stocks and bonds. Hibbard started a bit later but traveled much further, leaving New York for Cleveland, Ohio, to take a position as an apprentice designer at the Leon Rubay Company. After a few years learning the ropes with Rubay, Hibbard parlayed his talents as a draftsman to a part-time design job at a coachbuilder in Chicago, C.P. Kimball & Co., but he was not destined to stay there long.

By then, World War I had been raging for years in Europe, and Hibbard took up the call for assistance, enlisting in the Army Signal Corps. Thankfully for history, Hibbard arrived in France around the time armistice had been achieved in 1918, so instead of fighting in the trenches, Hibbard sent his resume to one of the most famous pre-war Parisian coachbuilders, Kellner et Cie., and was subsequently hired. Undoubtedly, this had to be the highlight of Hibbard’s young life, a foot in the door of a world-famous coachbuilder. But it was not to last—once his deployment was over, the US Army planned to ship Hibbard back to America, regardless of his new job. He wound up discharged in his old stomping grounds: New York City.

Meanwhile, Dietrich had been working hard on refining his own artistic career. Aside from his natural skill with an ink pen, Dietrich was also in possession of a mean fastball and monetized his talent with a side-gig as a pitcher playing semi-professional baseball in the local NYC leagues. Dietrich used the money he saved playing baseball to put himself through art school (yes, this is a supremely American story) and soon got a job at the most prestigious coachbuilder in the city, Brewster & Co.

As luck would have it, Dietrich’s desk in Brewster’s drafting department was right next to Hibbard’s. The two quickly began dreaming up their own venture, a firm where automotive styling would be paramount. Well-heeled customers would commission drawings from the designers, then take the sketches to their local coachbuilder for construction. A decentralized design firm needed a solid identity; Hibbard and Dietrich gave it an easy-to-swallow, yet French-sounding name: LeBaron, Carrossiers.

The road was far from easy. According to Dietrich, Willie Brewster’s parting words to him and Hibbard were: “You’ll never succeed. You’ve got to have experience.” In the beginning, the duo submitted freelance articles about automotive styling to magazines like Town & Country and Vanity Fair, as much for the extra cash as for the free publicity. In the beginning, they would dream of working on chassis as premium as this 1931 Pierce-Arrow Model 41 Convertible Victoria:

1931 Pierce-Arrow Model 41 Convertible Victoria by LeBaron

Identification No. 3050235

$345,000 | Asking

Ten years after its founding by Hibbard and Dietrich, LeBaron had established itself as a top-tier coachbuilder, directly dealing with companies like Pierce-Arrow and Packard to produce high-quality bodies like this in quantity. Though, like many premium objects amid the Great Depression, the quantity in question is minimal—Pierce-Arrow only commissioned 25 bodies from LeBaron, in an array of different configurations. Pierce-Arrow historian Bernard Weis estimates only 13 from that original group have survived. From that small number, this Convertible Victoria is the only example of its type known to exist.

Likely this is the most sporting configuration built by any coachbuilder on the Model 41 chassis—note the chopped windshield of this Convertible Victoria, as well as the signature Pierce-Arrow headlamps, integrated into the front fenders. In many ways, this Pierce-Arrow heralded the future of fully-integrated body design—so much so, it was believed to be a feature car exhibited at the 1931 New York Auto Show.

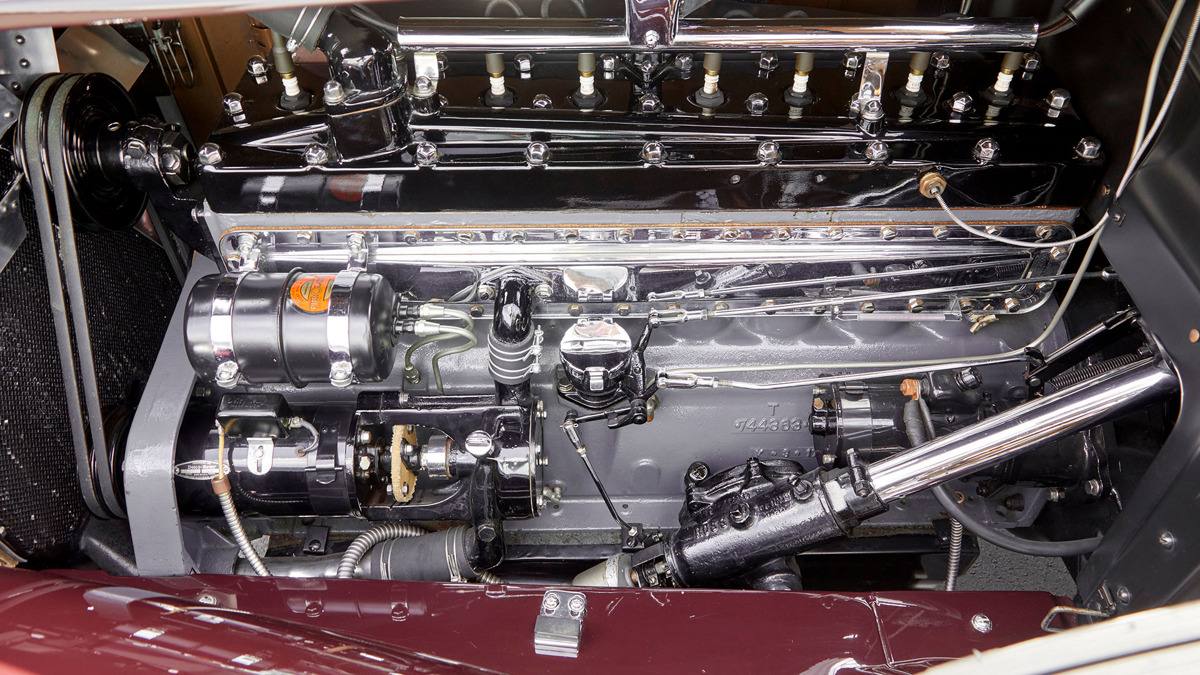

Powered by what Pierce-Arrow researchers have found to be the original, factory-installed engine after a ground-up, award-winning restoration, this example is endowed with an all-American spirit—a fusion of Pierce-Arrow engineering and LeBaron styling.

Perhaps fittingly, by the time this prestigious Pierce-Arrow was built by LeBaron, Hibbard and Dietrich had struck out on their own again, separately this time. Hibbard departed for Europe, this time for good, and formed an equally legendary partnership with Howard “Dutch” Darrin, whose designs were equally forward-thinking. Dietrich fended off one buyout attempt from Ford, but finally sold his own shares and decamped to Detroit for a job in Chrysler’s design department. And yet the creative spirit of Hibbard and Dietrich lived on in LeBaron, as this classic Convertible Victoria proves.