Forgive this writer for stating the obvious, but it is tough to build a new car company. So tough, in fact, that before Tesla was founded in 2003, the most recent automotive venture to launch prior to that started all the way back in 1925. Given the subject of today’s post, you’ve probably surmised that the company in question was Chrysler. As unlikely as it may have been at the time, Chrysler outlasted Pontiac, Packard, and Pierce-Arrow (as well as Dale, Davis, and DeLorean). For a firm that can sometimes seem like a brand in search of an identity, we present one of the greatest cars to wear the Chrysler nameplate.

1928 Chrysler Model 72 Roadster

Estimate: £50,000 - £70,000 GBP

From the beginning, company namesake Walter P. Chrysler understood that the way to prove the strength of his roadgoing cars was to take them racing. Bentley’s success at the 1924 running of the 24 Hours of Le Mans endurance race proved to be effective advertising for the brand, and the following year Bentley was joined by fellow British companies Sunbeam and AC Cars. And, thanks to new Parisian distributor Gustave Baehr, they would be joined by an American brand: Chrysler.

And yet Chrysler was no ordinary American brand. For starters, Chrysler was a second-generation immigrant. His father, Hank, grew up in Kansas City and even fought in the US Civil War, but his family were some of the founding members of Chatham, Ontario. (Coincidentally, Chatham is also the hometown of RM Auctions).

As a young man, Walter P. Chrysler’s rise from traveling railroad mechanic to works manager for the American Locomotive Company was sufficient to score a meeting with Charles W. Nash in 1911, then the president of Buick. Chrysler’s management skills (and creative cost-cutting) saved the division thousands, and earned the begrudging respect of William C. Durant, the feisty force behind General Motors. When Durant heard Chrysler was considering his own venture in 1916, he took the first train to Flint and offered him an astronomical salary of $10,000 per month for three years. Today, that would equate to $238,788 per month—enough to make him one of the highest-paid executives in America—but not sufficient to keep Chrysler captive for long.

Chrysler volleyed from Buick to Willys-Overland, finally landing at Maxwell Motor Company in 1921, and set about transforming it into a company worthy of his name. Fortunately for history, he had help: A trio of engineers nicknamed “The Three Musketeers.” Fred Zeder, Carl Breer, and Owen Skelton had been poached from Studebaker while Chrysler was running the Willys-Overland company, and while their turnaround attempt did not save Willys-Overland, they worked on a prototype of a new six-cylinder car that would form the basis of the first true Chrysler. Automotive historians today regard the 1924 Chrysler as the first modern car; the point of demarcation between rickety and refined. The twin lightning bolts on the first Chrysler logos are said to reference the “Z” in Fred Zeder, an acknowledgement of the Three Musketeers’ contribution to the quality of the early examples.

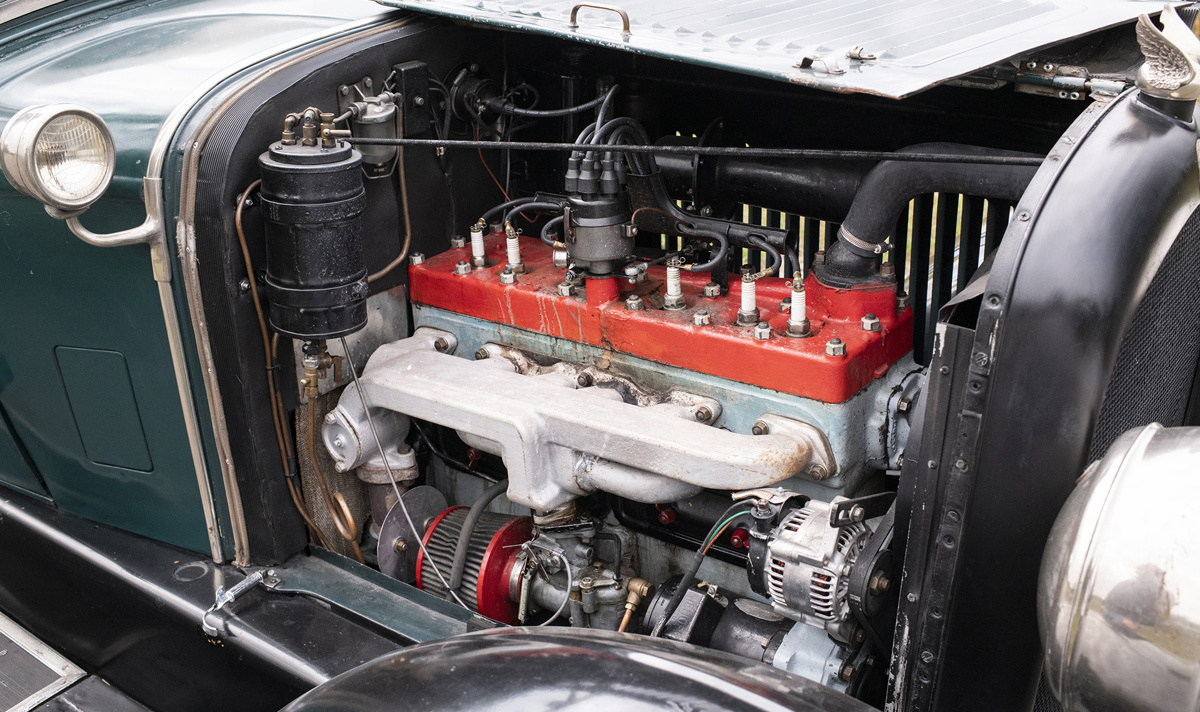

The Chrysler Six was a stout unit, which could achieve 70 m.p.h. and boasted a 5-to-1 compression ratio when most all competitors could only offer 4-to-1. With center-mounted spark plugs, the physical mechanics of the engine were designed to reduce detonation, increasing efficiency and making for a smoother ride. The in-cabin vibrations were reduced even further by Chrysler’s so-called “floating power” system—rubber mounts cradled the engine within the bay, an innovation found on every car today. The final futuristic feature is another we take for granted today—hydraulic brakes on all four wheels as opposed to two, a common way to reduce complexity at the time. These features combined gave Chrysler the confidence to campaign his all-new car at Le Mans only one year after the company was founded.

Unfortunately, bad luck bit the Chrysler team in 1925. After running a respectable seventh place at Le Mans, team driver Henri Stoffel wound up with his Chrysler Six stuck in a ditch while trying to avoid crashing into a slower car. The time wasted trying to get Stoffel’s car back on track cost Chrysler an official finish; the team only completed 117 of 119 total laps. However, they did take home an award from the Automobile Club de l’Ouest for fielding the quietest car in the competition.

In the three-year gap between 1925 and 1928, Chrysler went from an also-ran into a major contender, achieving both third and fourth-place at Le Mans in 1928, just behind Bentley and Stutz. Later that year in Italy, Chrysler Model 72 cars scored second and third place at the Mille Miglia. Back on the home front, Walter P. Chrysler was living the American dream. Chrysler acquired the Dodge Brothers Motor Company in 1928, shortening the brand to Dodge, and also establishing Plymouth in the process. With sales of Chrysler cars topping 360,399 in 1928, Chrysler made a healthy $31M profit and chose to use that money to bankroll the Chrysler building in New York City. Time Magazine’s “Man of the Year” for 1928? Of course, it was none other than Walter P. Chrysler.

If classic cars could be viewed through the same lens as fine wine, 1928 has proven to be an exceptional vintage for Chrysler. Perhaps prized even more today than in-period, examples like this Model 72 example shown above are still eligible for the same races that put the Chrysler brand on the map: Le Mans Classic and the Mille Miglia.

With a proven record, completing the Flying Scotsman Vintage Motor Rally just last year in 2019, this example punches far above its weight class, and is sure to be a car to watch at RM Sotheby’s London Fall auction on 31 October 2020. An American legend in every sense, Chrysler targeted the Model 72 for a discerning audience worldwide. His sales pitch to this supreme clientele still rings true today: “For them, I saw a car with the power of a super-dreadnaught, but with the endurance and speed of a fleet scout cruiser.” Sounds even more appealing today.