Monterey 2011

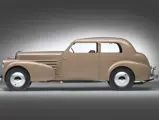

1932 Marmon HCM V-12 2 Door Sedan Prototype

{{lr.item.text}}

$800,000 - $1,000,000 USD | Not Sold

| Monterey, California

| Monterey, California

{{internetCurrentBid}}

{{internetTimeLeft}}

151 bhp, 368 cu. in. OHV aluminum V-12 engine, three-speed manual transmission, sliding-pillar independent coil-spring front suspension, transverse leaf-spring independent rear suspension, and four-wheel mechanical drum brakes. Wheelbase: 134"

- An historic, highly advanced prototype

- Well-known provenance and ownership history

- A multiple concours award winner, including 2001 Pebble Beach Best in Class

- Subject of an Automobile Quarterly feature by Beverly Rae Kimes

The winter of 1930-31 was a bittersweet time for Howard Marmon. His pièce de résistance, the landmark Marmon Sixteen, debuted to great acclaim at the Chicago Auto Salon in November, and the following month he received a medal for outstanding achievement from the Society of Automotive Engineers. Although a second shift was added to the assembly line when full production began in April, Marmon turned to deficits as the Depression deepened, and two rounds of pay cuts were followed by layoffs for most of the engineering staff. Into this milieu, Mr. Marmon took drastic action and a revolutionary new model was conceived.

The new car originated as a sketch created by Howard Marmon after meetings with Fred Moscovics, Marmon’s former vice president and general manager who had moved on to Stutz, and chief engineer George Freers. The name HCM, derived from Howard Marmon’s initials, was applied late in the car’s development.

It was to have a tubular backbone and four-wheel independent suspension, using transverse leaf springs front and rear. Two parallel front springs connected to sliding pillars, a concept initiated by Lancia in 1921, which were anchored to outriggers from the narrow center chassis. At the rear, four springs, two forward and two aft, mounted to the differential housing, which formed the center of the chassis. The outer ends of the springs supported the wheel hubs. Drive was by swing axles. The result was very low un-sprung weight, but ride quality suffered, so the front springs were changed to coils mounted on the pillars above the steering knuckle, as in Lancia’s design.

The transmission was a three-speed unit mounted rigidly to the tubular backbone, through which the driveshaft ran. Behind the transmission was an epicyclic overdrive, in turn rigidly bolted to the differential housing. Problems with lubrication and the shift linkage caused this arrangement to be abandoned and replaced by a standard Marmon Sixteen transmission mounted directly behind the engine.

Howard Marmon decided on a V-12 engine, more powerful than an eight but much more economical than his flagship V-16. Engineering was expeditious and based on the V-16, retained the V-16’s bore, stroke, 45-degree cylinder bank angle and wet-liner aluminum construction. It developed 151 bhp at 3,700 rpm, three-quarters of the V-16’s output from an engine three-quarters its size. Initial tests at the Indianapolis Motor Speedway in July of 1932 confirmed acceleration from 10 to 50 mph in a then-remarkable 12.77 seconds, with a 113-mph maximum speed clocked with racing driver Wilbur Shaw at the wheel.

The HCM’s body was similarly radical. It had as its genesis a wooden model made by a college student. In creating the Marmon Sixteen, Howard Marmon had contracted its body design to Walter Dorwin Teague Associates in New York. The firm, which took its name from its founder and principal designer, was responsible for such icons as Kodak’s Brownie camera, Steuben glassware, Texaco gas stations and interiors for several generations of Boeing airliners. Mr. Teague, however, did not like automobiles and did not even drive and so assigned the Marmon project to his car-crazy son, Walter Dorwin Jr., then an M.I.T. student. The Marmon Sixteen design came together when Teague Jr., known as Dorwin, came home from Boston to work weekends.

After his experience with the Sixteen, Dorwin Teague built a model of, as he described it, “what a car really should look like.” His influences were an evocative Renault ad in a French magazine and the enclosed fenders on Frank Lockhart’s 1928 Stutz Blackhawk speed record car. The 1/10-scale model, with its long hood, aft-mounted cabin and truncated luggage compartment, was in the Teague design office when Howard Marmon came to discuss the project. Marmon was captivated, and once back at Indianapolis, he sent Teague a set of chassis drawings to get things started.

The HCM’s form followed Dorwin’s model but with several refinements. The cabin moved slightly forward, and the trunk became more of a bustle. In place of the model’s freestanding headlamps, he integrated a pair of the stylish narrow Woodlites into the edge of the grille shell. Like the model, a four-passenger coupe, its doors were reversed to become front opening. Dorwin visited Indianapolis and found a mockup of the car to his liking. After returning to New York, however, he received a new set of drawings in which the car had gained a hood ornament, which he had purposely omitted. The lights were now fender-mounted, à la Pierce-Arrow.

Built in a special shop in a corner of Marmon’s plant, the HCM was personally financed by Howard Marmon at an estimated cost of $160,000, and upon completion in the fall of 1933, the company was in receivership. Howard Marmon and George Freers took it on a tour of the nation’s auto manufacturers to see if someone else could produce it. However, none of the Big Three, nor any of the independents, were interested. In the end, Marmon took the car home to his North Carolina estate and wrapped it in cellophane.

There it remained until his death in 1943. Prominent car collector James Melton, the operatic tenor, tried to buy it, but Marmon’s widow would not sell. Instead, she gave the car to Fred Moscovics, then working for A.O. Smith, manufacturer of automobile frames and other industrial products, in New York. Moscovics in turn traded it to Allan Floyd of Milwaukee, son of an A.O. Smith vice president, for a Stutz. Floyd enjoyed working on the HCM, by then in need of some TLC, until he departed for college, after which the car saw little use. Designer Brooks Stevens, a friend of Floyd’s father, was starting the collection that eventually became a museum in suburban Milwaukee. Floyd stored the car there for a time, eventually giving it to Stevens for the museum collection. Stevens painted it dark blue but otherwise left it largely untouched – and unused.

The next owner purchased the car from the Stevens Museum in 1999, after Mr. Stevens’ death. Initially interested in some other cars from the Stevens Collection, he decided to purchase the HCM after researching its history – becoming, in his words, “the only one of five owners to pay for the car.” All previous transfers had been gifts or trades. His first priority was to return it to the original color; the impetus for a complete restoration came from Dorwin Teague, who, despite his deep involvement, had never actually seen the car. It was entrusted to George Kovanda of Chicago Restorations, who completely disassembled and rebuilt it, finishing with the correct shade of light tan. Completed in 2001, it was reunited with its designer in an emotional moment at that year’s Pebble Beach Concours d’Elegance, compounded by the car’s achieving a perfect score and winning Best in Class.

Since then the HCM has earned a special award at Amelia Island in 2002 and took Best in Class at Cranbrook in 2004. It was also judged a 100-point car in national CCCA Grand Classic competition and has achieved Senior status. Dorwin Teague died in 2004 at age 94. His reunion with the HCM must have ranked among the high points of his prolific design career. The Marmon HCM is one of the most significant yet relatively unknown prototype cars ever built. Acquired by the vendor in July 2007, it has been extensively chronicled by the late Beverly Rae Kimes in Automotive Quarterly and represents a singular opportunity to acquire a car of exceptional historical importance.